Rising food prices hurt poor people around the globe, especially in low- and middle-income countries (Artuk 2022, Chepeliev 2022). And in places where the rule of law is rarely the primary governing principle for negotiations among involved parties, rising food prices can also lead to riots and social unrest (Bellemare 2015, Ubilava 2022).

While protests and riots are typically urban phenomena, a surge in agricultural commodity prices, particularly of cereal grains, can trigger conflict in rural areas as the value of appropriable output increases (McGuirk and Burke 2020). Understanding the peculiarities of agrarian conflict is important in countries where agriculture represents a large share of the economy and employs a considerable share of the population. Most African countries fall in this category.

An important nuance of agriculture is its seasonality: farmers generate income when they harvest and then sell their crops. And the seasonality of agricultural income translates into a seasonality of conflict.

In our new study (Ubilava et al. 2022), we examine 55,000 attacks staged between 1997 and 2020 by different perpetrators, such as state forces, rebel groups, and political and identity militias (ACLED Project, Raleigh et al. 2010), and find that violence against civilians increases during the harvest season and dissipate as the year progresses.1

Seasonal violence in Africa emanates largely from the governments’ own political militias: different factions vie for dominance by attacking their rivals and rivals’ supporters at a time when they are realising their income for the year – during the harvest. Depriving their rivals of that income is a great way to do the most damage, to put their own faction in an advantageous position, and, if their militias steal the harvest, to make money for themselves.

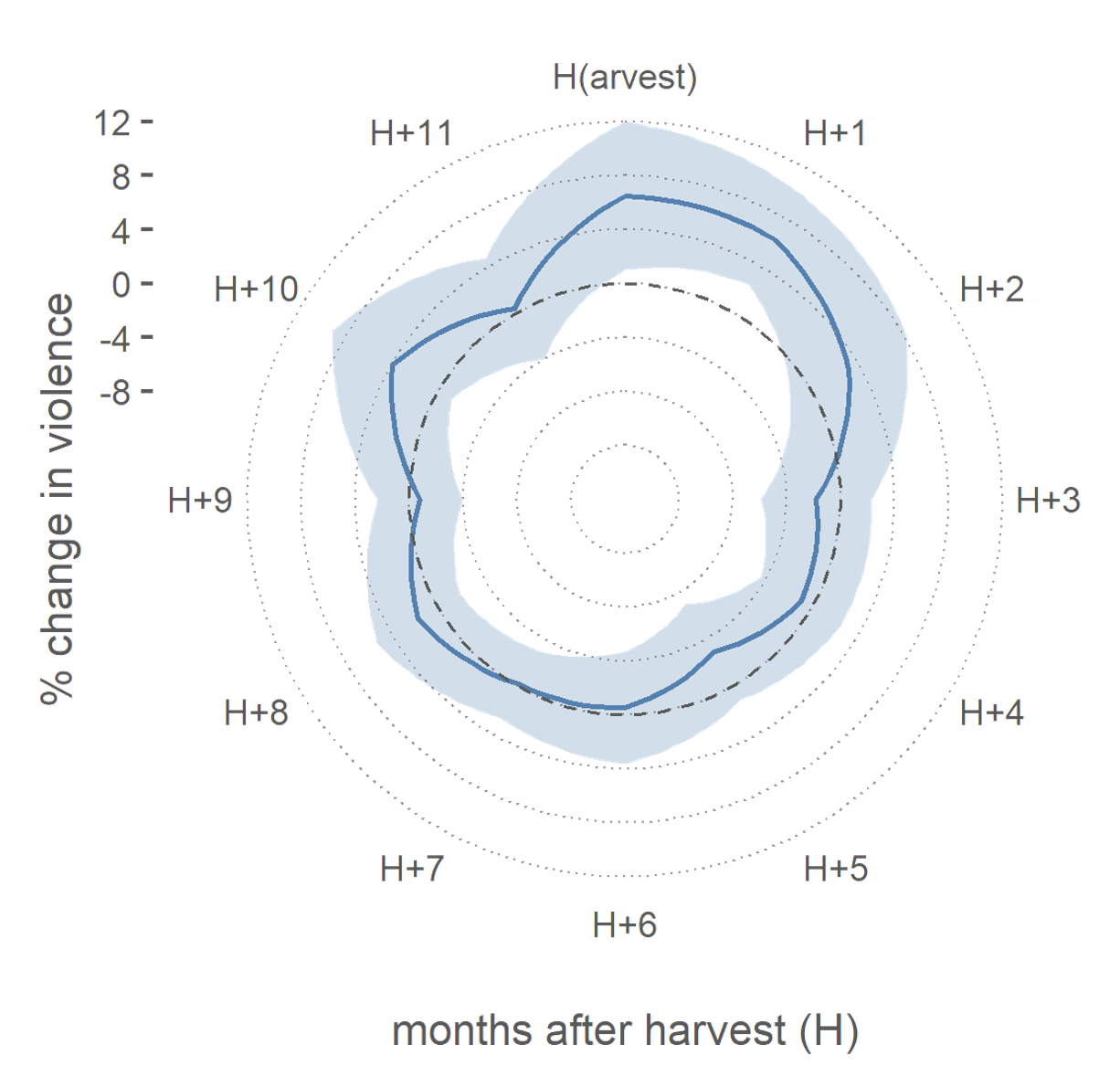

To put the main results of the study into perspective: at a location with ‘average’ cropland, a 35% year-on-year increase in cereal prices – a change comparable to that observed in March and April of 2022 (FAO 2022) – will lead to a 6% increase in violence in the harvest month and the subsequent month relative to the baseline probability of violence in the African croplands. Figure 1 illustrates this.

Figure 1 The seasonal effect of cereal prices shocks on political violence

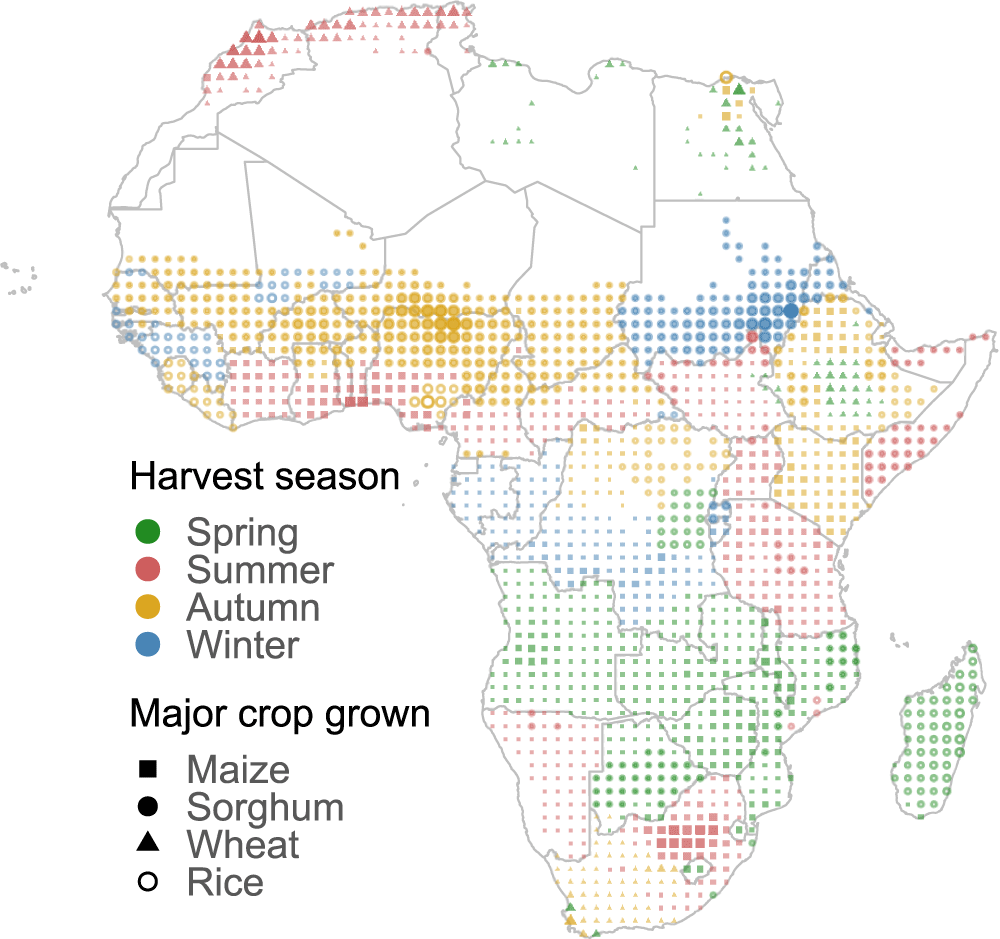

To the extent that different cereals are grown in different parts of Africa, and because harvest seasons vary across locations (Sachs et al. 2010), there may be varying hot spots across the continent as the calendar year progresses. Figure 2 summarises the harvest seasons of major cereal grains (namely of maize, rice, sorghum, and wheat) across Africa. A year-on-year increase in the global prices of these cereal grains during boreal spring can have very different geographical repercussions than a similar price increase during boreal autumn, for example.

Figure 2 Harvest season of major cereals grown across Africa

The key finding of the study, which identifies a crucial temporal nuance in the income–conflict nexus, helps pinpoint, on a yearly basis, when conflicts are going to get worse: harvest time is when the money for many people in developing countries comes in, but also the moment of greatest risk. Moreover, as pro-government militias appear to be the most likely perpetrator, aid to countries may be better directed at governments that have clamped down on factional fighting.

In summary, soaring global commodity prices of cereal grains increase the risk of conflict not only in urban areas but also in rural areas of low- and middle-income countries. Thus, in addition to vigilance in urban areas that are prone to social unrest, there may also be a need to enhance food security or protect civilians in agricultural areas during harvest seasons as a means of protecting the food supply.

References

Artuc, E, G Falcone, G Porto, and B Rijkers (2022), “War-induced food price inflation imperils the poor”, VoxEU.org, 01 April.

Bellemare, M F (2015), “Rising Food Prices, Food Price Volatility, and Social Unrest”, American Journal of Agricultural Economics 97(1): 1–21.

Chepeliev, M, M Maliszewska and M F Seara Pereira (2022), “Agricultural and energy importers in the developing world are hit hardest by the Ukraine war’s economic fallout”, VoxEU.org, 06 May.

FAO (2022), Food Price Index, accessed 12 May 2022.

McGuirk, E and M Burke (2020), “The Economics Origins of Conflict in Africa”, Journal of Political Economy 128: 3940–3997.

Raleigh, C, A Linke, H Hegre and J Karlsen (2010), “Introducing ACLED: An Armed Conflict Location and Event Dataset: Special Data Feature”, Journal of Peace Research 47(5): 651–660.

Sacks, W J, D Deryng, J A Foley and N Ramankutty (2010), “Crop Planting Dates: An Analysis of Global Patterns”, Global Ecology and Biogeography 19(5): 607–620.

Ubilava, D (2022), “Russia’s war on Ukraine is driving up wheat prices and threatens global supplies of bread, meat and eggs”, The Conversation, 15 March 2022.

Ubilava, D, J Hastings and K Atalay (2022), “Agricultural Windfalls and the Seasonality of Political Violence in Africa”, 27 February.

Endnotes

1 This work is undergoing revisions and the results are subject to change, although no substantial adjustment of the present key findings is anticipated.