“We are being afflicted with a new disease of which some readers may not have heard the name, but of which they will hear a great deal in the years to come," John Maynard Keynes wrote almost a century ago, "namely, technological unemployment.”

(Keynes 1930)

If Keynes' original readers found those worries were misplaced, today there is concern that these gloomy predictions may soon come true (Brynjolfsson and McAfee 2012, Ford 2016). Bolstering such concerns, a range of low-skill and medium-skill occupations exposed to automation have suffered employment declines and sluggish or even negative wage growth (Autor et al. 2003, Goos and Manning 2007, Michaels et al. 2014).

Plenty of research speculates on what might happen when the robots arrive. Frey and Osborne (2013), classified occupations by how susceptible they are to automation and concluded that 47% of US workers are at risk in the next 20 years. McKinsey (2016) claims the same statistic is 45%, and The World Bank estimates that this number for the OECD as a whole is 57% of workers. Arntz et al. (2016), however, disagree. They argue that, within an occupation, many workers specialise in tasks that cannot be automated easily, and so their estimate for OECD jobs at risk is only 9%.

Whether 9% or 57% or jobs are at risk, there is no guarantee that firms would replace those workers with robots. That would depend on the costs of automation, and how much wages change in response to this threat. Additionally, even if an industry introduces robots to do specific jobs, productivity improvements may create new jobs in the firm, or other occupations might be able to expand.

New research

In new research, we go beyond these feasibility studies, and estimate what is already happening due to the introduction of robots (Acemoglu and Restrepo 2017). We investigate the equilibrium impact of industrial robots in local US labour markets. These machines are defined by The International Federation of Robotics as “an automatically controlled, reprogrammable, and multipurpose [machine]” (IFR 2014; see also Graetz and Michaels, 2015). Industrial robots are fully autonomous machines that can be programmed to perform several manual tasks such as welding, painting, assembling, handling materials, or packaging. This definition excludes other types of capital, such as software, that may also replace labour, and machines designed for a single function, such as cranes, circuit printers, textile looms or coffee machines.

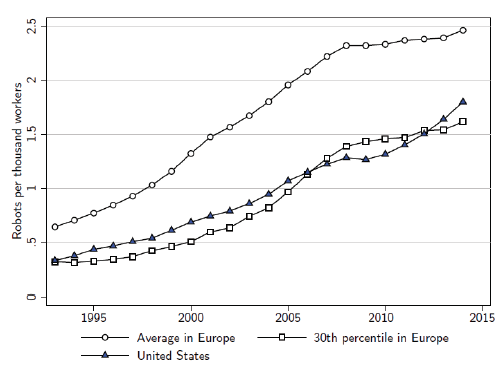

In 2007 there were four times as many industrial robots in the US and Western Europe as in 1993 (Figure 1). The IFR estimates that there are currently between 1.5 and 1.75 million industrial robots in operation, a number that could increase to 4 to 6 million by 2025 (Boston Consulting Group 2015).

Figure 1 Industrial robots per 1,000 workers in the US and Europe, 1993-2007

Source: International Federation of Robotics.

Robot usage is far from evenly spread across the economy. The automotive industry employs 39% of existing industrial robots, followed by the electronics industry (19%), metal products (9%), and the plastic and chemicals industry (9%). Some of these industries were also exposed to import competition from Mexico; whereas Chinese imports and offshoring affected a different set of industries. The actual facts are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Industry-level changes in the use of robots, Chinese imports, capital stock and IT capital.

Basic theory guiding the empirics

We use a simple model in which robots and workers compete in the production of different tasks (after Acemoglu and Autor 2011, Acemoglu and Restrepo 2016). In this model, the share of tasks performed by robots varies across industries, and there is trade between labour markets specialising in different industries. The model decomposes the aggregate impact on employment and wages into a negative displacement effect on workers who lose their jobs, and a positive productivity effect across the wider economy.

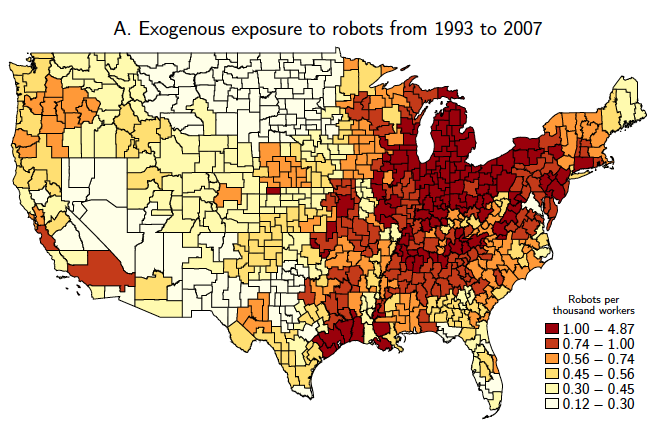

The model also shows that we can summarize the net impact of robots on local labour markets – commuting zones in our application – through a measure of the exposure of these areas to robots. The exposure is defined as the sum over industries of the national penetration of robots into 19 industries, multiplied by the employment share of that industry in that labour market. To compute it, we calculate employment shares by industry in each zone from Census data. Figure 3 shows that US commuting zones differ substantially in their exposure to robots. This variation allows us to estimate the impact of industrial robots on wages and employment in these local labour markets.

Figure 3 Geographic distribution of the exposure to robots, 1993-2007

When computing our measure of exposure to robots, one concern is that the adoption of robots by US industries might be a response to problems (or opportunities) in these industries or the local economy of commuting zones that house them. To remove the influence of these confounding factors, we focus on the spread of robots coming from advances in technology, which we proxy using the industry-level spread of robots in other advanced economies (this is similar to what Autor et al. 2013 and Bloom et al. 2016 do for the increase in imports from China).

The impact on employment and wages

Our results show a strong relationship between a commuting zone’s exposure to robots and employment. In the areas most exposed to robots, between 1990 and 2007 both employment and wages declined in a robust and significant way. During this period, we estimate that, relative to other areas, the introduction of a new robot per 1,000 workers in a commuting zone reduced the local employment-to-population ratio by 0.37 percentage points and local wages by 0.73%. This is equivalent to 6.2 workers losing their jobs for every robot.

Although these numbers suggest that exposed commuting zones are doing worse than the rest in terms of employment and wages, they do not necessarily reflect the US-wide effects of robots. The adoption of robots in one commuting zone could lower production costs, and via trade, enable other industries to create employment in the rest of the economy. Such indirect benefits would be missed in our cross-sectional comparisons. To account for these gains, we use our model to recompute the impact of robots allowing for trade between commuting zones, and found that the employment and wage effects were smaller - but not by much. The exact impact depends on how easy it was to substitute between goods produced in different places, the cost savings from robots and the elasticity of the local labour supply. Using reasonable estimates for these elasticities and our estimates to discipline the calibration of the remaining parameters in our model, we found that allowing for trade still implies each new robot per thousand workers reduced employment to population ratio by 0.34 percentage points and cut wages by about 0.5% (as opposed to 0.73%). If we further take account of the potential spillovers from reduced employment and wages in industries adopting the robots onto other local non-tradable industries, these numbers might be even smaller: about 0.18 percentage points lower employment to population ratio and 0.25% slower wage growth for every one robot per thousand workers (corresponding to about three workers losing their jobs because of one more robot).

Clearly industrial robots are not the only innovations being implemented at any time, and we might have erroneously attributed to robots the effects of many other technologies that could also displace labour. This is not the case: our results are the same when we control for the increase in overall capital intensity and IT capital by industry. Note also that exposure to robots is only weakly correlated with various other trends. Nor is our measure of exposure to robots related to past trends in employment and wages in the pre-robot era from 1970 to 1990. Indeed, controlling for broad industry composition (shares of manufacturing, durables, construction and so on), for detailed demographics, for exposure to Chinese and Mexican imports, for the decline in routine jobs, and for offshoring opportunities does not change our results.

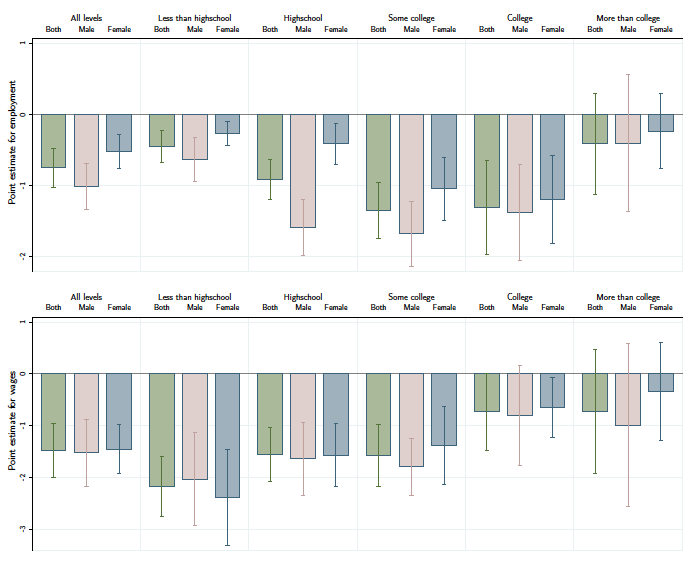

In the commuting zones most exposed to robots, the employment effect is strongest for routine manual, blue collar, assembly and related occupations, and for workers with less than college education. But no one, it seems, has escaped entirely. Slicing the data by type of employment or education (Figure 2), we find no overall positive impact on any group.

Figure 4 Relationship between the exposure to robots, and Census employment and log of hourly wages by education group, 1993-2007

Source: Acemoglu and Restrepo (2017).

Future impacts

This is only a first step. Alternative strategies for estimating the aggregate implications of the spread of robots and other labour-replacing technologies would complement our approach.

We believe as well that the negative effects we estimate are both interesting and surprising, because of the small offsetting employment increases in other industries and occupations. So far, there are relatively few robots in the US economy, and so the number of jobs lost due to robots has been limited to between 360,000 and 670,000 jobs. If the robots spread as predicted, future aggregate job losses will be much larger. For example, BCG (2015) has an 'aggressive' scenario in which the world stock of industrial robots would quadruple by 2025. In our estimates, that would imply a 0.94-1.76 percentage points lower employment to population ratio, and 1.3-2.6% lower wage growth between 2015 and 2025. These are sizable effects. But it should also be noted that even under the most aggressive scenario, we are talking about a relatively small fraction of employment in the US economy being affected by robots. There is nothing here to support the view that new technologies will make most jobs disappear and humans largely redundant.

References

Acemoglu, D and D Autor (2011) “Skills, tasks and technologies: Implications for employment and earnings,” Handbook of Labor Economics, 4: 1043–1171.

Acemoglu, D and P Restrepo (2016) “The Race Between Machine and Man: Implications of Technology for Growth, Factor Shares and Employment” NBER Working Paper No. 22252.

Acemoglu, D and P Restrepo (2017) “Robots and Jobs: Evidence from US Labor Markets” NBER Working Paper No. 23285.

Arntz, M, T Gregory, and U Zierahn (2016) “The Risk of Automation for Jobs in OECD Countries,” OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 189, OECD

Autor, D H, D Dorn, and G H Hanson (2013) “The China Syndrome: Local Labor Market Effects of Import Competition in the United States.” American Economic Review 103(6): 2121–68

Autor, D H, F Levy and R J Murnane (2003) “The Skill Content of Recent Technological Change: An Empirical Exploration,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(4): 1279–1333.

Bloom, N, M Draca, and J Van Reenen (2016) “Trade Induced Technical Change? The Impact of Chinese Imports on Innovation, IT and Productivity,” The Review of Economic Studies, 83(1): 87–117.

Boston Consulting Group (2015) The Robotics Revolution: The Next Great Leap in Manufacturing.

Brynjolfsson, E and A McAfee (2014) The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies, W. W. Norton & Company.

Chui, M, J Manyika, and M Miremadi (2016) "Where machines could replace humans—and where they can’t (yet)", McKinsey Quarterly, July.

Ford, M (2015) The Rise of the Robots, Basic Books, New York.

Frey, C B and M A Osborne (2013) “The Future of Employment: How Susceptible are Jobs to Computerisation?” Mimeo. Oxford Martin School.

Goos, M and A Manning (2007) “Lousy and Lovely Jobs: The Rising Polarization of Work in Britain,” The Review of Economics and Statistics, 89(1): 118-133.

Graetz, G and G Michaels (2015) “Robots at Work,” CEP Discussion Paper No 1335.

International Federation of Robotics (2014) World Robotics: Industrial Robots.

Keynes, J M (1930) “Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren,” in Essays in Persuasion. Palgrave MacMillan.

Michaels, G, A Natraj and J Van Reenen (2014) “Has ICT Polarized Skill Demand? Evidence from Eleven Countries over Twenty-Five Years,” Review of Economics and Statistics, 96(1): 60–77.

World Bank (2016) World Development Report 2016: Digital Dividends.