In 2018, the provision of everyday services available to public consumers using artificial intelligence (AI) expanded. In this column, I discuss not only the public acceptance of innovation, but also the role of standards in promoting products and services related to AI technology.

Social acceptance of new technology

A variety of products and services using AI-related technology will be developed in the future. At the same time, the social acceptance of technology requires consumers to engage with it in greater numbers. What measures can be taken to promote the acceptance of technology by consumers? In Rogers’s theoretical model, which captures the pattern of diffusion for new ideas, diffusion can generally be represented by a convex curve (Rogers 2003). But for products or services based on new emerging technologies, such as those related to AI, the rate of initial dissemination seems to be relatively low.

Products and services that use AI-related technology can process things faster and with greater accuracy and less bias than humans. The technology can avoid the inevitable fatigue, misunderstanding, or intentional bias to which human beings are susceptible. If we circumvent mistakes in usage in the appropriate field, satisfaction among consumers for these services is expected to increase. On the other hand, users find it difficult to distinguish products and services based on AI-related technology because the technology is associated with an information-processing method. The difficulty that users face in recognising technology can be an impediment to its diffusion and acceptance.

Characteristics of goods and services

To explain why consumers find certain products more difficult to comprehend than others, I sort goods and services into three categories: search goods, experience goods, and credence goods. Search goods are those products and services whose details and quality can be understood from information provided before purchase, such as a personal computer. One can reasonably explain the utility that search goods will provide to consumers by reading performance data from a catalogue. On the other hand, the value of experience goods cannot be gauged without use. Education and medical services fall under this category – they can be understood to some extent in advance, but consumers cannot know the level of satisfaction the services will bring without actually experiencing them.

The search goods and experience goods described here are not mutually exclusive products and services. In many cases, search goods have the properties of experience goods. The approximate performance of a car can be understood from its promotional material, but the actual comfort is difficult to ascertain without taking a ride.

With this in mind, we turn to the third category, credence goods, as a way to classify products and services that use AI-related technology. Because AI-related technology relies on computational algorithms, it is difficult to distinguish whether AI is even in use, or differs from other technologies, when viewed from the outside. Credence goods include products and services whose internal information is not commonly detected even after they’ve been used, making them difficult for consumers to understand (e.g. genetically modified food). Goods and services using AI-related technology generally have the characteristics of credence goods, as it is difficult for consumers to tell whether or not a product contains this technology. The spread of new technology may be delayed when information on goods and services is difficult to communicate to consumers.

The role and challenges of standards in technology dissemination

One remedy for the difficulty described above is to provide information on the outside of the device, where it is visible to the consumer. In other words, affixing a label to the product can not only communicate whether AI-related technology is being used, but also allow consumers to decide whether to selectively choose and use it. This process is generally called labelling. It requires us to determine criteria for applying appropriate labels and thus to determine standards for AI-related technology.

The formulation of such standards plays a substantial role in spreading new technologies. An effective standard includes necessary definitions of terminology, measurement methods, and safety stipulations. Establishing common, public frameworks of knowledge for new technologies promotes their proliferation and better understanding. In the case of nanotechnology, the formulation of standards that provided clarity on basic concepts took place swiftly after the new technology emerged and are believed to have played a major role in its spread (Blind and Gauch 2009).

As of December 2018, technical classifications of AI-related technology were not clearly defined within international standards systems, and the boundaries of this technology were considered ambiguous (ISO 2015, Tamura 2019). For promoting social acceptance of the technology in the future, establishing standards is an important issue needing resolution (see the appendix below).

Conclusion

In order to promote social dissemination of AI-related technology, the difficulty in distinguishing between goods or services that actually use it is an issue that needs to be resolved. Standards and indications (artificial intelligence labelling)1 can play an effective role as one means of solving this problem and promoting dissemination of the technology.

References

Blind, K and S Gauch (2009), “Research and standardization in nanotechnology: evidence from Germany”, The Journal of Technology Transfer 34: 320–342.

ISO (2015), “International classification for standards 2015”, Geneva.

Rogers, E M (2003), Diffusion of Innovations (5th Edition), New York: Free Press.

Tamura, S (2019), “Determinants of the survival ratio for de jure standards: AI-related technologies and interaction with patents”, Computer Standards & Interfaces 66: 103332.

Appendix

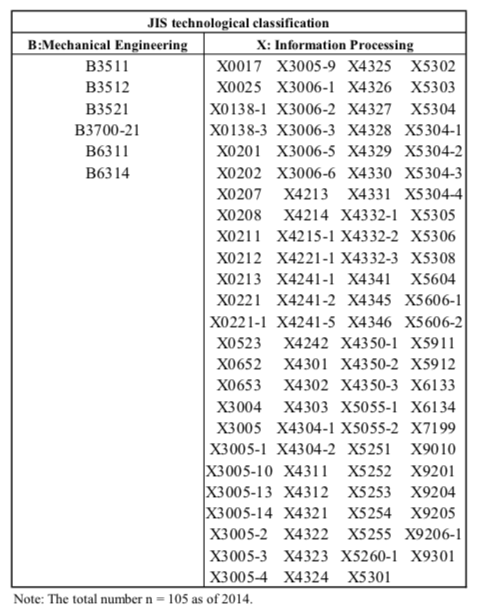

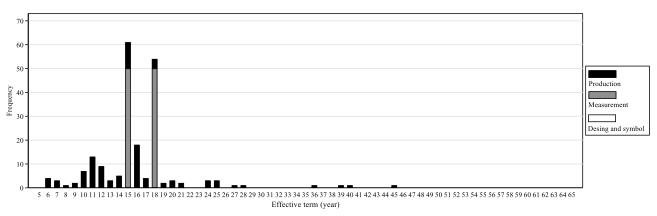

The author is currently creating a technical classification for AI-related technology and reclassifying the Japanese Industrial Standards (JIS) based on new classifications. There are about 100 active and withdrawn AI-related standards as of 2014 (Table 1). The distribution of effective terms of those standards is presented in Figure 1.

Table 1 List of AI-related standards

Figure 1 Effective terms of AI-related standards

Endnotes

[1] The JIS, ISO, and IEC systems still do not contain technological classifications for AI (as of 2018). This is also called ‘marking’. There is no substantial difference between labelling and marking; the two expressions refer to the same process. In this context, it is worth pointing out that an ‘AI mark’ has the same meaning and effect as an AI label. Authentication is also performed to confirm whether the good in question qualifies to use the mark or label. The authentication, which can take the form of either self-authentication or third-party authentication, is often used as part of the standards and certification process.