This year’s annual conference of the European Fiscal Board (EFB) attracted more than 300 policymakers, academics, and practitioners from all over the globe. The meeting’s virtual format allowed for a much larger representation of independent fiscal institutions (IFIs) among the speakers and audience. The ambition is to provide an additional forum for IFIs to share their insights on fiscal policy developments and stimulate a broader debate with the community of fiscal experts.

The discussions reflected the concerns of the time: the implications of the Covid pandemic for fiscal policymaking, the sustainability of public finances and, more broadly, the future of the EU fiscal framework. Acknowledging the profound impact of the crisis on the economy and public finances, Valdis Dombrovskis, the European Commission’s Executive-Vice President, opened the conference pointing out that many of the questions on the agenda were not entirely new – high government debt combined with low economic growth and subdued inflation had occupied policymakers well before the Covid-19 shock. The crisis has magnified existing issues, making their resolution more urgent.

The debate revolved around three main topics particularly relevant for the future of the EU fiscal framework: (1) the high debt levels of member states coming out of the crisis; (2) the need for better and more stable medium-term fiscal planning; and (3) the importance of the quality of public finance.

Coping with high levels of government debt

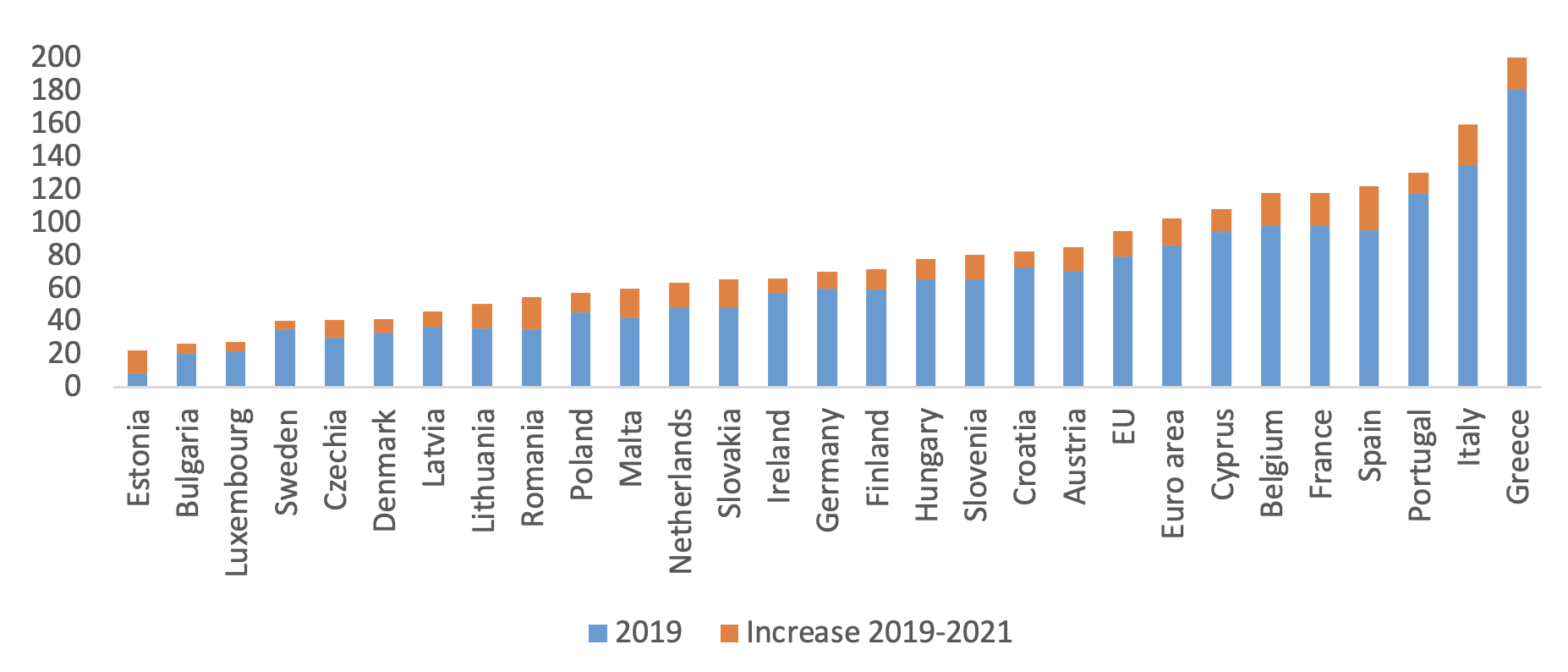

The Covid crisis has led to a sudden jump in government debt, only adding to already elevated pre-pandemic debt-to-GDP ratios in many EU member states (see Figure 1). Coming out of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) more than a decade ago, governments were expected to return to lower levels of debt. Some member states succeeded, others much less, if at all. Various factors were at play such as low economic growth and unresolved political economy problems preventing governments from taking advantage of good economic times to (re)build fiscal buffers (European Fiscal Board 2020).

Figure 1 Government debt-to-GDP ratios in the EU

Source: European Commission

Naturally, all eyes are and should currently be on ensuring a swift recovery. This point was underscored by all keynote speakers at the conference. At the same time, forecasts predict debt ratios to plateau in the coming years and to gradually decline over time. This may be a repeated fallacy. Indeed, the accuracy of fiscal forecasts of international institutions is not encouraging. Jonathan D. Ostry’s (IMF) analysis of medium-term public debt forecasts in more than 170 economies reveals a clear and widespread optimism bias. For example, after the GFC, five-year-ahead forecasts for the debt-to-GDP ratio were on average off by 10% of GDP as forecasters repeatedly or naively expected a steady decline in the medium term. Over-optimism also tends to be larger the higher the initial debt.

This does not bode well for the current debt projections. Forecast errors may turn out to be even more extreme, if one looks at the experience of Japan, where, as highlighted by Junji Ueda (Ministry of Finance, Japan), it took several years before the new, low-inflation and low-growth environment was internalised in official projections.

IFIs have played an important role in containing the optimism of government forecasts by critically assessing and validating government projections (Jonung and Larch 2006). As Eddie Casey (Irish Fiscal Council) shows, EU IFIs have become important sources of budgetary forecasts to ensure more realistic predictions underpinning government budgets. Aside from traditional stochastic debt sustainability analysis, IFIs also produce deterministic analysis in the form of different ‘scenarios’. These are particularly helpful in highly unusual times, when past patterns in the data are unlikely to be repeated. Both analytical tools have merits and should be seen as complements, as Claudia Braz (Banco de Portugal) pointed out.

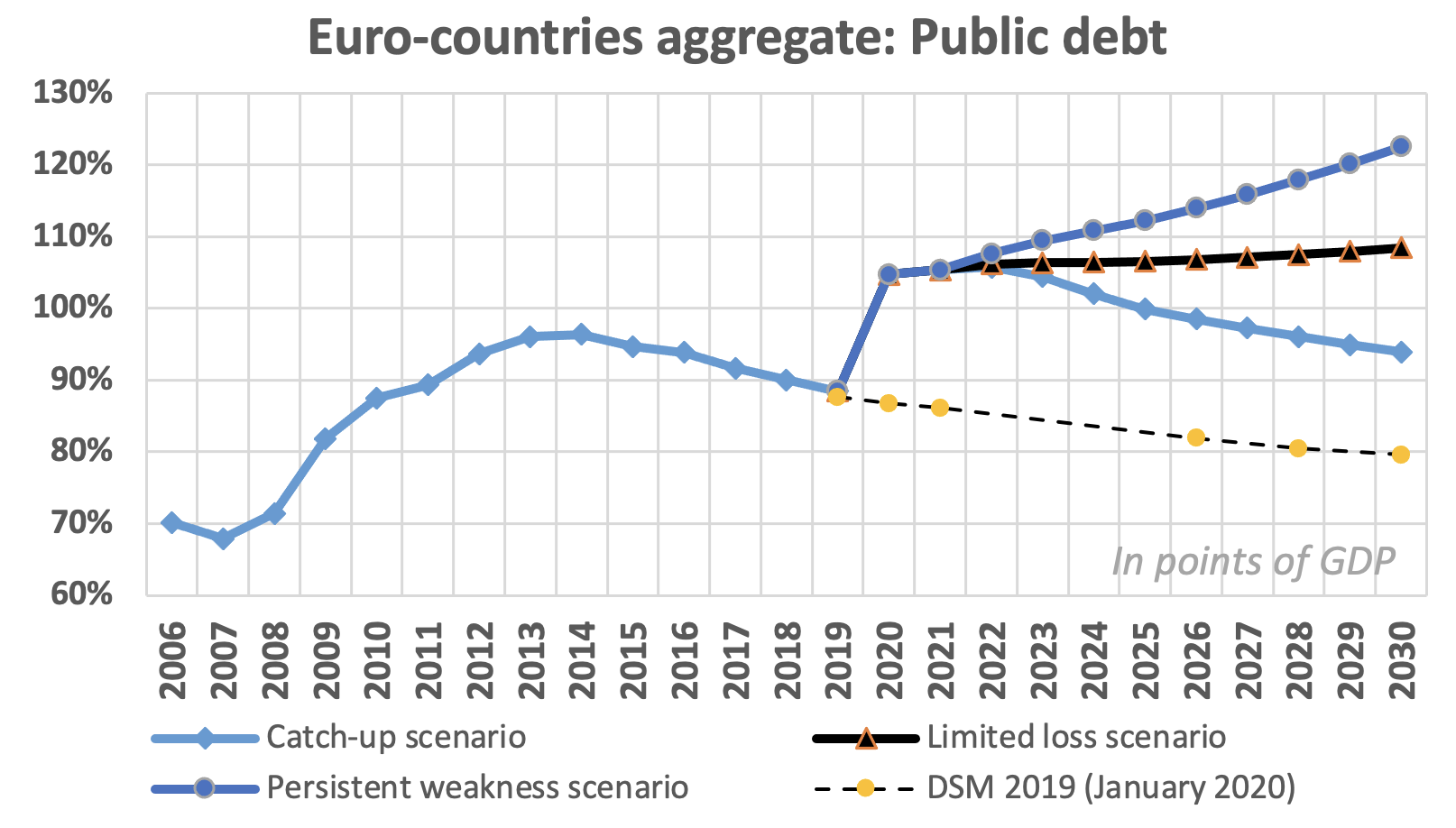

As an example, Nicolas Carnot (French High Council of Public Finances) presented three stylised debt sustainability scenarios for six euro area member states.

Figure 2 Three scenarios of government debt in euro area countries

Notes: The euro-area countries considered are France, Germany, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands and Spain. ‘Catch-up’ scenario: return to the pre-pandemic path of potential GDP); ‘limited loss’ scenario: based on the same potential GDP growth as before the crisis; ‘persistent weakness’ scenario: potential GDP growth rate below pre-crisis.

Source: Carnot et al. (2021)

The stark differences across scenarios underscore the sensitivity of forecasts to the underlying assumptions on potential growth, especially when the debt-to-GDP ratios are high. The scenarios range from a gradual decline back to pre-crisis debt levels, to steadily rising debt ratios. In addition, implicit debt linked to pre-existing pension claims and significant guarantees extended during the pandemic, threaten debt sustainability without being fully accounted for. Charles Goodhart (Professor Emeritus, London School of Economics) warned that pandemic-related deficits are but a blip compared to ageing related costs that will exert growing pressure on public finance in the next decades. In the end, all forecasts point to formidable challenges ahead.

Building the foundation through quality public finance

In recent years, ultra-low interest rates have contained sovereign borrowing costs despite sharply rising debt levels, thereby supporting debt sustainability – for now. As Isabel Schnabel, Member of the ECB’s Executive Board, noted in her keynote speech, monetary policy has been very accommodative throughout the past decade and, faced with the current crisis, reacted swiftly with further new unconventional policy tools – foremost the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP). At the same time, constrained by the zero lower bound on nominal policy rates, monetary authorities also look at fiscal policy to provide unconventional support for stabilisation purposes. In this context, Giancarlo Corsetti (Cambridge University) argued that independence should not be used as an argument against the complementarity of monetary and fiscal policy. An appropriate policy mix and, hence, coordination of macroeconomic instruments has rarely been as decisive as now.

While financial markets expect real interest rates to stay low for some time, the ECB will have to keep a close eye on inflation, while governments cannot bet on an indefinite continuation of current policies. Consequently, while in the current low-interest environment issuing debt may look like a free lunch for governments, in truth, it seems unlikely to hold. Kenneth Rogoff (Harvard University) suggested that advanced economies may have ‘graduated’ from outright default but reminded how periods of high debt are associated with lower economic growth and that a high debt burden may reduce the fiscal flexibility during the next crisis.

True, interest rates have been outstripped by growth rates in recent history for advanced economies and global real interest rates have been on a long-term gradual decline. However, the currently ultra-low interest rates are well below any historical trend and there is no guarantee the negative interest-growth differential will continue indefinitely. At the very least, governments face an increased sensitivity of debt sustainability to interest rate spikes or persistent growth slumps. Some EU member states have already suffered from protracted low growth. It will be one of the key tasks of governments to enhance potential growth coming out of the crisis in order to dampen the pressure on outright consolidation.

Against this background, the quality of public finance is stepping into the spotlight. Aside from effective tax collection, much of the debate has recently focused on the allocation of government spending. The crucial point here is not necessarily how much the government spends, but how and on what. By extension, this also applies to debt-financed spending. As Commissioner Gentiloni put it in his speech, there is ‘good’ debt (for research, education, infrastructure, hospitals) and ‘bad’ debt (for non-productive spending). This logic is relevant not only for supportive measures now but also in the eventual consolidation phase. In the past, EU governments had the tendency to disproportionately cut back public investment. The EFB has repeatedly called for stronger focus on growth-enhancing government expenditures and proposed ways to stimulate these also through the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) – beyond the already existing, but scarcely used, ‘investment clause’.

The Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) is a welcome new financial instrument to boost public investment. It is a unique chance to show the viability of such an EU facility, thereby strengthening the case for a euro area central fiscal capacity. As Thiess Büttner (Friedrich–Alexander University Erlangen–Nürnberg) pointed out, the asymmetric distribution of RRF grants not only supports those member states disproportionally affected by the pandemic, but incidentally also those with high debt levels. Moreover, the accompanying reform packages to be outlined and approved in the Recovery and Resilience Plans have the potential to structurally improve the quality of public finance. If implemented successfully, the RRF can play an important role towards enabling member states to grow out of their debt; it is an opportunity Europe cannot afford to miss.

Looking beyond the next budgetary year

One pre-existing weakness in the fiscal domain that has worsened over the years is medium-term fiscal planning. Medium-term perspectives were supposed to become more important in the reformed SGP, but they have recently lost in significance (European Fiscal Board 2019a). The notorious focus on the short-term has been one of the contributing factors to many member states entering the Covid crisis with only limited fiscal space. IFIs and the EFB have been critical on the implementation of European as well as national fiscal rules in practice. Lucía Rodríguez Muñoz (Independent Authority for Fiscal Responsibility, Madrid) presented evidence on the implementation gap, which hinders effective medium-term fiscal planning. While planning for the following year tends to provide a good guidance on eventually realised outlays, plans of outer years are “frequently aspirational rather than constraining”. Best practises often rely on a strong political commitment and in a few cases fixed fiscal targets, which are also binding for the outer years – for example, throughout an electoral cycle. Fiscal targets should have clear counterparts in budgetary execution and should be easy to communicate, for example, through to medium-term expenditure growth ceilings. Gilles Mourre (European Commission, DG ECFIN) noted that moving to a debt anchor and net expenditure rules is likely to be conducive to strengthening the medium-term perspective of the fiscal framework.

The future of the EU fiscal framework

The European Commission will relaunch its economic governance review1 in 2021. This provides the opportunity to address some of the well-documented weaknesses of the EU fiscal framework (e.g. European Fiscal Board 2019b). The crisis has added urgency to the review.

The impact of the pandemic also doubles down on the question of how to square the very high debt levels with the current debt rule. The debt benchmark requires a fiscal adjustment towards the 60% of GDP threshold with a reduction of the distance to the threshold by, on average, one-twentieth on an annual basis. Nicolas Carnot’s contribution showed that if the debt benchmark were enforced, it would require an onerous adjustment effort for countries with debt ratios well above 100% and low economic growth. A review could introduce a differentiated adjustment pace (Thygesen at al. 2020). Several speakers echoed the calls by the EFB for a fiscal framework that combines a debt anchor and a single operational rule (net expenditure growth). Such a framework would be less complex and easier to communicate. It would continue to pursue long-term sustainability of public finances but with fiscal variables that are under more direct control of the government (expenditure growth) and translate into better compliance, provided enforcement can be ensured. There are of course many other aspects of the SGP that could be addressed in the review. Lorenzo Bini Smaghi (Société Générale), for example, alluded to the asymmetry of the fiscal rules while others commented on observed pro-cyclicality of fiscal policy.

Overall, expectations ran high for the economic governance review, initially launched in February 2020 and put on hold when the Covid pandemic hit the EU. The activation of the general escape clause of the SGP provides a unique opportunity to return to a fully-fledged, rules-based fiscal policy with a simpler, nimbler, and more resilient fiscal framework.

References

Carnot et al. (2021), “The public debt outlook in the EMU post Covid: A key challenge for the EU fiscal framework", Network of EU IFIs, March.

European Fiscal Board (2019a), Annual Report 2019, Brussels.

European Fiscal Board (2019b), Assessment of EU fiscal rules with a focus on the six and two-pack legislation, Brussels.

European Fiscal Board (2020), Annual Report 2020, Brussels.

Jonung, L and M Larch (2006), “Improving fiscal policy in the EU: the case for independent forecasts”, Economic Policy 21(47): 492–534.

Thygesen, N, R Beetsma, M Bordignon, X Debrun, M Szczurek, M Larch, M Busse, M Gabrijelcic, E Orseau and S Santacroce (2020), “Reforming the EU fiscal framework: Now is the time”, VoxEU.org, 26 October.

Endnotes

1 https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/economic-and-fiscal-policy-coordination/eu-economic-governance-monitoring-prevention-correction/economic-governance-review_en