Since 16 March 2014, the EU (in concerted action with the US) has frozen assets and imposed travel bans on 33 persons and an individual bank. On 20 March, Russia counteracted with the reciprocal blacklisting of EU and US officials. This pattern of tit for tat raises the question of the comparative vulnerability of the EU and Russia. In assessing this vulnerability, is not just the ability to inflict economic damage that matters, however, but also the way economic damage translates into political change. This means that one needs to consider the political system. It will be more difficult to influence decision-makers that do not attribute decisive weight to the potential damage done to their countrymen than to influence their counterparts in the European democracies.

Table 1 reports findings of two simple logit models that analyse the Peterson Institute database of economic sanctions (Hufbauer et al. 2008). Bilateral trade is represented in percentage of either the target’s total trade flow or its GDP. The models predict seven out of ten sanction cases correctly, and show that the positive impact of trade linkage and the negative impact of autocracy are highly significant.

Table 1. Success of sanctions: LOGIT estimates of the success score of sanctions, 1946–2000

| Trade linkage |

Share in total trade |

Share in target trade |

|---|

| Number of observations |

166 |

161 |

| Trade linkage |

1.1** |

3.5*** |

| Sanction period |

-0.69*** |

-0.68*** |

| Autocracy score |

-0.11** |

-0.15*** |

| Constant term |

0.27 |

0.44 |

| Log likelihood |

-93.2 |

-90.3 |

| Errors Type I (false positive) |

38% |

37% |

| Errors type II (false negative) |

26% |

25% |

| Percent correct |

71% |

71% |

*** 99%; ** 95% significance.

Source: Van Bergeijk (2009), Table 6.4 p. 131.

We can use the estimated models to uncover the relative probabilities that full-scale sanctions succeed. In 2012, bilateral trade flows between Russia and the EU constituted 22% of Russian GDP and 3% of EU GDP. While the economic impact of full sanctions thus would seem to hurt Russia more than the EU, the impact on the EU is by no means negligible (Russia’s 2012 share in EU external trade was about 10%). Moreover, the autocracy score for Russia dampens the impact that the economic sanctions will have politically (while EU and US democracy scores in the Polity IV data set are 10, the score for Russia is only 5). Based on these data, Figure 1 provides a comparative perspective on the efficacy of economic sanctions.

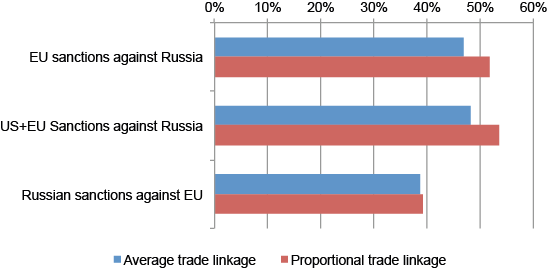

Figure 1. Expected probability that sanctions succeed

EU sanctions against Russia have a 47-52% chance of succeeding (the calculation pertains to the second year that sanctions have been imposed). This chance can be improved a little if the US joins the sanctions, but that impact is small because US trade relations with Russia are much less intensive. It is important to note that these calculations are optimistic on three accounts.

- First, the calculations have been based on autocracy scores for 2012 (the most recent year for which data are available) and are probably outdated, i.e. too low.

- Second, sanctions have a less than average probability of succeeding if they aim at discouraging military interventions (such as the annexation of the Crimea).

- Third, the economic and political costs are unevenly distributed between Europe and a forceful boycott and embargo would thus be difficult to achieve.

On the other hand, the Russian sanctions against the EU stand a 39% chance of succeeding, which is definitely not negligible, especially in view of the fact that much less (if any) internal coordination is necessary to impose counter sanctions. Putin’s letter of 10 April to use gas as a weapon in the Crimean crisis can be seen as an implicit threat – or a reminder – of his ability to exploit EU dependence on Russian gas as well.

In this context, we can understand the EU’s choice to impose smart sanctions only. The costs of counter sanction that Europe could suffer – although smaller than those experienced by Russia – would translate easier into political pressure due to the stronger democratic nature of European governments. The Russian tit for tat threat is realistic.

References

Peter A.G. van Bergeijk (2012), “Failure and success of economic sanctions”, VoxEU.org, 27 March

Hufbauer et al. (2008), Economic Sanctions Reconsidered, 3rd edition, Washington DC.