Motivated by the sluggish recovery after the global financial crisis, a recent literature has developed showing that recessions cause persistent or ‘scarring’ effects on the level of GDP. The reason behind this are cyclical shocks that affect the supply side of the economy through several channels, thereby shaping the long-term trend (Cerra et al. 2020). As the COVID-19 pandemic constitutes an unprecedented shock to the global economy, its potential scarring effects are difficult to predict. Assessing the scarring effects of past crises might however provide some indication as to how the COVID-19 shock could affect potential output (Martín Fuentes and Moder 2020).

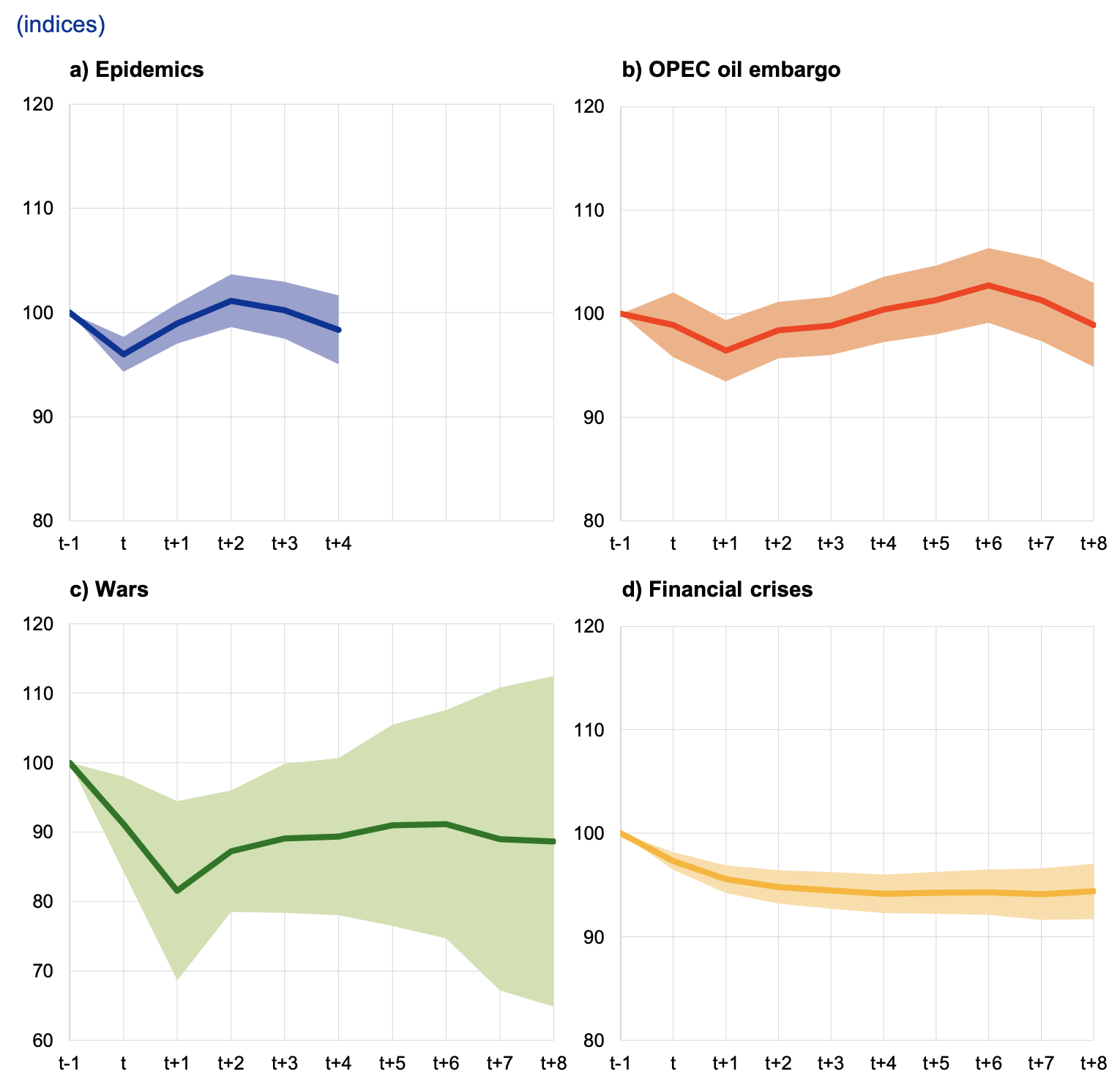

A local projections analysis1 (following Jordà 2005) of past epidemics suggests that their initial impact on the level of potential output is relatively short-lived, tending to dissipate two years after the end of the epidemic (see Figure 1, upper-left panel).2 However, it should be noted that the past epidemics considered in the analysis were – with the exception of the swine flu – mostly localised events which are not comparable to a major global pandemic (see also Jordà et al. 2020, who find significant long-lasting macroeconomic consequences from 15 major pandemics since the 14th century). We hence additionally consider the impact of two other exogenous crises on potential output: the 1973-74 oil embargo imposed by the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), which can be regarded as an exogenous negative supply shock for the affected countries,3 and major wars.4 Our results suggest that the oil embargo only had a negative effect on potential output in the first year after the shock (upper-right panel). Similarly, the results for major wars (lower left panel) suggest that following a severe initial impact, post-war economic recoveries tend to be steep and with no significant longer-lasting scarring effects (i.e. beyond four years).5

Figure 1 Scarring effects of past epidemics and other crises on potential output levels

Sources: ECB staff calculations based on Feenstra et al. (2015) and Laeven and Valencia (2018).

Note: The continuous lines indicate the impact of the respective event in year t on the level of potential output up to the period t+8, i.e. eight years after the end of the event, and the shaded areas depict the 95% confidence interval. The impact on potential output is estimated with a local projections approach, based on a global panel that includes all events simultaneously, four lags of potential output growth to control for endogeneity, and country-fixed effects. As most of the epidemics considered in the analysis are relatively recent, the sample only allows their impact to be calculated until four years after the end of the epidemic. Potential output is defined as the level of output that is consistent with the productive capacity of an economy.

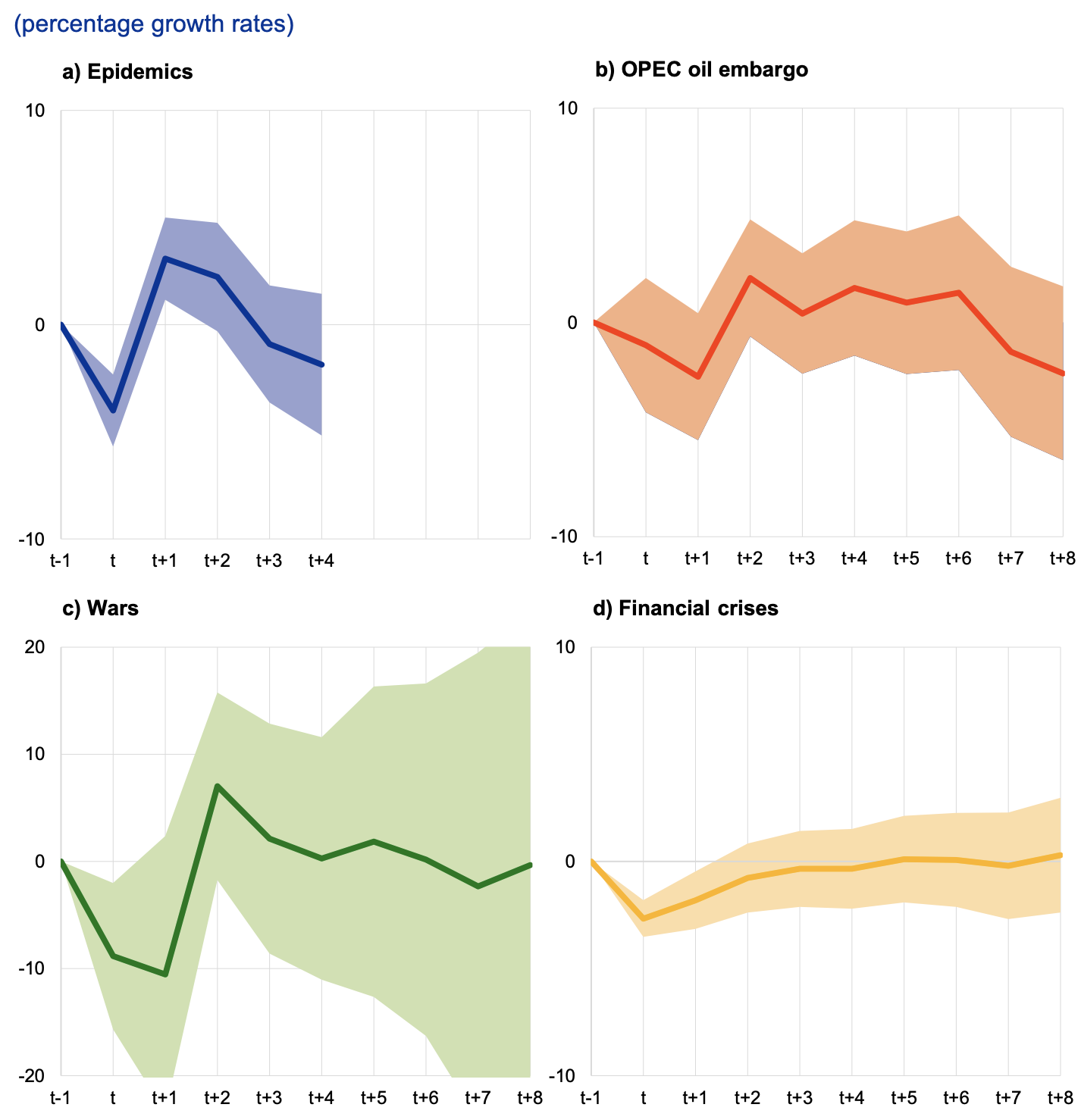

In contrast, financial crises are associated with a significant and very persistent downward shift in potential output. The results for past financial crises (as examples of endogenous crises, i.e. those triggered by the accumulation of economic imbalances) suggest a loss of around 5% even after eight years, in line with the recent literature discussed above. This is supported by the fact that, for recessions caused by financial crises, no overshooting in growth rates can be observed after the end of the recession, pointing to long-lasting scarring effects on the level of potential output (see Figure 2). This is different from the exogenous crises (i.e. epidemics, the OPEC embargo and wars), where the initial contraction is followed by above-normal growth rates, bringing the economy’s potential output back to its long-term trend path.6

Figure 2 Impact of past epidemics and other crises on potential output growth

Sources: ECB staff calculations based on Feenstra et al. (2015) and Laeven and Valencia (2018).

Note: The continuous lines indicate the impact of the respective event in year t on the growth rate of potential output up to the period t+8, i.e. eight years after the end of the event, and the shaded areas depict the 95% confidence interval. The impact on potential output is estimated with a local projections approach, based on a global panel that includes all events simultaneously, four lags of potential output growth to control for endogeneity, and country-fixed effects. As most of the epidemics considered in the analysis are relatively recent, the sample only allows their impact to be calculated until four years after the end of the epidemic. Potential output is defined as the level of output that is consistent with the productive capacity of an economy.

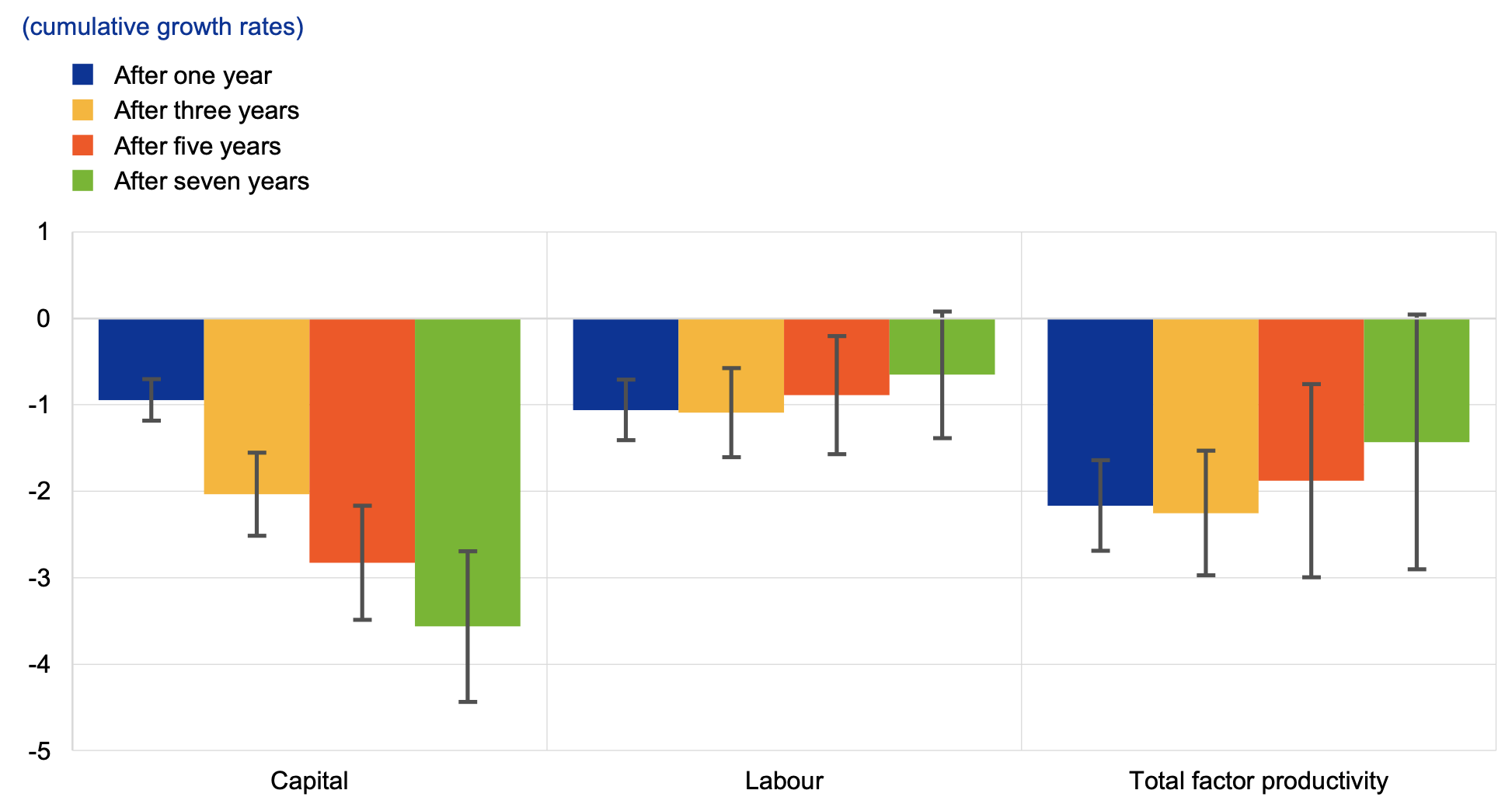

In order to gain more insights into how past financial crises left scarring effects on potential output, the local projections approach is applied to the individual components of potential output.7 Our results indicate that all three supply-side components of the production function are initially affected by a financial crisis (see Figure 3). While the negative impact on total factor productivity and labour input starts to subside after approximately three years, there are adverse and persistent effects on the capital stock, which is the main source of the long-term scarring effects of financial crises.

The jury is still out on whether the long-term impact of COVID-19 will resemble more those of the epidemics and other exogenous shocks examined above (i.e. no scarring effects) or those of financial crises (i.e. persistent scarring effects). Looking at the individual components of potential output, COVID-19 could negatively affect the capital stock similarly to past financial crises. Capital depreciation is likely to have increased as a result of COVID-19, especially in capital-intensive sectors hit by the crisis such as the airline industry, where parts of the capital stock could become obsolete, as well as in other sectors that are struggling as a result of the demand shock.8 Furthermore, post-crisis public finance consolidation needs combined with difficult economic prospects for companies may contribute to a period of protracted under-investment.

Figure 3 Impact of financial crises on supply-side components of potential output

Sources: ECB staff calculations based on Feenstra et al. (2015) and Laeven and Valencia (2018).

Notes: The bars indicate the impact of financial crises on the respective supply-side components after the number of years shown since the end of the crisis. The error bars represent a 95% confidence interval. The impact on potential output is estimated using a local projections approach, based on a global panel that includes all events simultaneously, four lags of potential output growth to control for endogeneity, and country-fixed effects. Potential output is defined as the level of output that is consistent with the productive capacity of an economy.

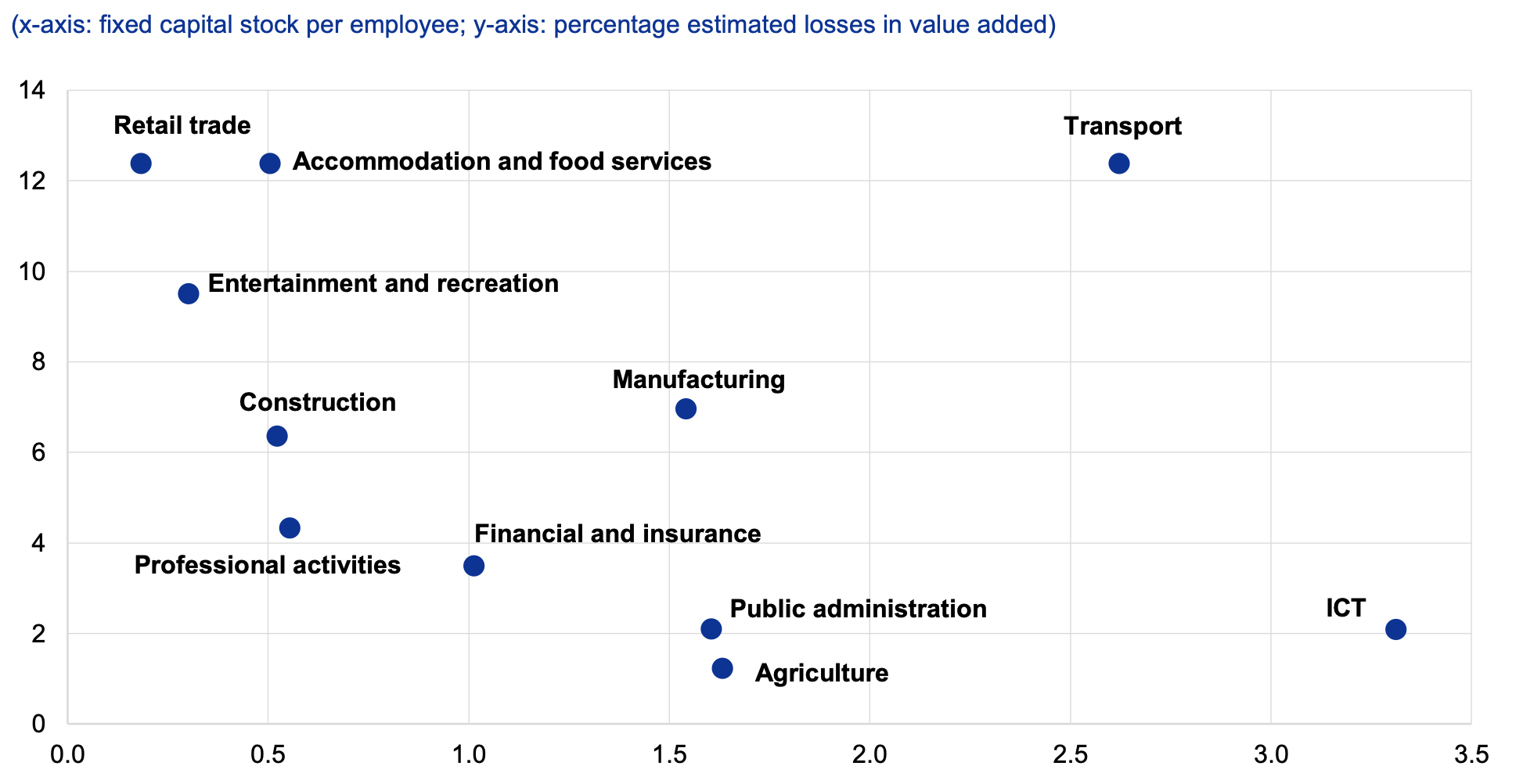

As the COVID-19 shock has above all hit labour-intensive sectors, the initial impact on labour supply could be stronger compared with past financial crises. With the exception of transport, the sectors most affected by the COVID-19 containment measures (i.e. retail trade, accommodation and food services, entertainment and recreation) tend to be more labour- rather than capital-intensive (see Figure 4). At the same time, even sectors not targeted by the lockdown measures may have been hit indirectly through reduced sales of intermediate goods to affected sectors (Laeven 2020). Whether those employment losses will become more permanent will depend on the speed of the reallocation of workers across sectors and firms. Pandemic-related labour market consequences, such as a reduction in the labour force due to an increase in the number of discouraged workers or more limited global migration flows to advanced economies, might lead to a sustained contraction in the labour force. This contraction, combined with the impact on the accumulation of human capital from widespread school closures, could exacerbate the loss in labour supply (Burgess and Sievertson 2020). At the same time, it should be recognised that the losses depend on the policy response and the success of labour market policies in mitigating these effects.

Figure 4 Sectoral losses as a result of the COVID-19 containment measures and capital/labour intensity ratio

Sources: ECB staff calculations, Adarov and Stehrer (2019) and Stehrer et al. (2019).

Notes: Sectoral losses as a result of the COVID-19 lockdown measures are based on an ECB staff assessment for a sample of globally systemic countries and calculated as an unweighted average. The capital/labour intensity ratio is calculated as the fixed capital stock (in 2017) divided by the labour input (in number of employees in 2017) for each sector, based on the unweighted average of a sample of 19 countries.

The COVID-19 crisis could affect total factor productivity in several ways. First, the impact of COVID-19 could temporarily lock resources in unproductive sectors, and the reallocation of productive resources towards fast-growing industries is likely to take time.9 In addition, innovation could be impaired through lower spending on research and development, both in the public sector on account of consolidation needs and in the private sector owing to elevated uncertainty. Furthermore, reshoring of global value chains in the aftermath of the COVID-19 crisis could hamper innovation and knowledge spillovers across countries. At the same time, the increased use of digital technologies spurred by the COVID-19 crisis has the potential to accelerate the digital transformation of the global economy and therefore contribute positively to total factor productivity.

Authors’ note: The views expressed here are those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect those of the ECB or the Eurosystem and should not be reported as such.

References

Adarov, A and R Stehrer (2019), “Tangible and Intangible Assets in the Growth Performance of the EU, Japan and the US”, wiiw Research Reports 442, The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies.

Burgess, S and H Sievertson (2020), “Schools, Skills and Learning: the impact of Covid-19 on education”, VoxEU.org, 1 April.

Bodnár, K, J Le Roux, P Lopez-Garcia and B Szörfi (2020), “The impact of COVID-19 on potential output in the euro area”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 7, ECB.

Cerra, V, A Fatás and S C Saxena (2020), “The persistence of a COVID-induced global recession”, VoxEU.org, 14 May.

Dieppe, A (ed.) (2020), “Global Productivity: Trends, Drivers, and Policies”, World Bank.

Feenstra, R C, R Inklaar and M P Timmer (2015), "The Next Generation of the Penn World Table", American Economic Review 105(10): 3150-3182.

Jordà, Ò (2005), "Estimation and Inference of Impulse Responses by Local Projections", American Economic Review 95(1): 161-182.

Jordà, Ò, S R Singh and A M Taylor (2020), “Longer-Run Economic Consequences of Pandemics”, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Working Papers No 2020-09.

Laeven, L (2020), “COVID-19 and the effects of social distancing on the economy”, VoxEU.org, 31 August.

Laeven, L and F Valencia (2018), “Systemic Banking Crises Revisited”, IMF Working Papers No 18/206.

Ma, C, J Rogers and S Zhou (2020), “Modern Pandemics: Recession and Recovery,” International Finance Discussion Papers 1295, Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Martín Fuentes N and I Moder (2020), “The scarring effects of past crises on the global economy”, Economic Bulletin Issue 8, ECB.

Stehrer, R, A Bykova, K Jäger, O Reiter and M Schwarzhappel (2019), “Industry Level Growth and Productivity Data with Special Focus on Intangible Assets”, wiiw Report on methodologies and data construction for the EU KLEMS Release 2019, The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies.

Endnotes

1 The following results are based on local projections from a panel data model covering 117 countries from 1970 to 2017. The independent variables represent cumulative potential output growth in each year. Regressors include autoregressive terms of four lags, dummies for the respective events as well as country-fixed effects. Data sources are the Penn World Tables (Feenstra et al. 2015) for potential output and its respective sub-components, and Laeven and Valencia (2018) for financial crises.

2 Past epidemics include SARS (2003), swine flu (2009-10), MERS (2013), the Ebola virus (2014-15) and the Zika virus (2016). Countries are treated as affected if they registered at least ten cases.

3 The estimation sample includes the following countries affected by the OPEC oil embargo: Canada, Japan, the Netherlands, Portugal, South Africa, the United Kingdom and the United States. While the OPEC oil embargo had only a short-lived effect on the embargoed countries compared with the countries not subject to the embargo, the permanent rise in oil prices due to the oil price shocks in the 1970s, particularly the second oil price shock, may have had a more permanent effect on global potential output (see also Bodnár et al. 2020).

4 The following wars are included in the sample: the Lebanese Civil War (1975-90), the Gulf War in Iraq (1990-91), the Yugoslav Wars (1991-99), the Sierra Leone Civil War (1991-2002), the Second Congo War (1999-2003), the Iraq War (2003-11), the Syrian Civil War (2011-present) and the Iraq Civil War (2014-17).

5 The very wide confidence intervals however point to sizeable heterogeneity in the long-term impact of wars.

6 Assessing the impact of health crises on actual GDP instead of potential output, Ma et al. (2020) find that output is still below its pre-shock level five years later.

7 In line with the short-lived impact on potential growth discussed above, the impact of epidemics, the OPEC embargo and wars on the individual components of the supply side is either short-lived or not significant at all and is therefore not discussed further here. The only exception is the adverse impact of epidemics on labour supply (including human capital), which intensifies over time. The results for epidemics are broadly similar to the results of recent research by the World Bank (see Dieppe 2020).

8 At the same time, as Bodnár et al. (2020) point out, there could be some offsetting effects in the short run as the life span of existing assets might be prolonged due to a less intensive use during the lockdown.

9 Once this has taken place, however, aggregate productivity might benefit from such a reallocation of resources towards more productive sectors. Additionally, the COVID-19 shock might have a stronger impact on low-productivity firms, which could in principle have a positive effect on aggregate productivity. See Box 2 in Bodnár et al. (2020).