About one million refugees and irregular migrants arrived in Europe in 2015 alone, and a further 0.4 million in 2016.1 Knowing their motivations, socio-demographic characteristics, and intended destination countries is important for several reasons. First, information on the motivations of migrants helps to distinguish between the refugee crisis and challenges associated with irregular migration and helps in planning optimal policies to alleviate the humanitarian crisis. Second, refugees’ self-selection has implications for rebuilding their home countries. The more skilled refugees are, the more difficult it is to fill the gap they leave once the country enters the reconstruction stage. Third, knowing the skill distribution and intended destinations of refugees and irregular migrants who make it to the transit countries is helpful in planning integration policies, and thereby contributes to social stability in host countries and in intended destination countries. In 2015 and 2016, concerns about refugees and irregular migrants resulted in the re-introduction of border controls inside the Schengen area, disrupting the central principle of intra-EU free mobility and intra-European trade and supply chains. Worries about immigration have powered the rise of populist parties and candidates in Austria (Halla et al. 2017), Denmark (Dustmann et al., forthcoming), France (Edo et al., 2019), Germany (Otto and Steinhardt 2014), and Greece (Dinas et al. 2019).

A global perspective

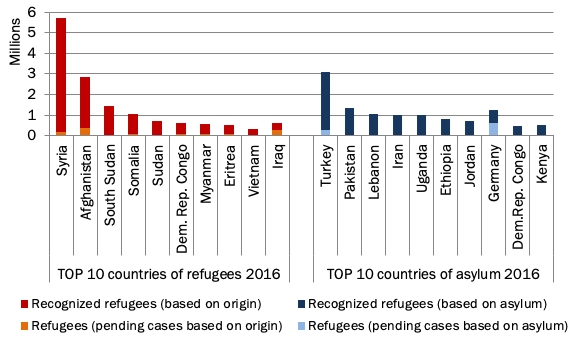

Nearly 66 million people were forcibly displaced worldwide at the end of 2016 (UNHCR 2017). The total number of people seeking safety across international borders as refugees reached 22.5 million, with more than half of all refugees worldwide coming from only three countries: Afghanistan, South Sudan, and Syria (UNHCR 2017). In 2016, the largest numbers of refugees came from countries in Asia and Africa, and nine of the ten countries hosting the largest numbers of refugees were also in Asia and Africa, with Germany being the only European country on the list (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Main countries of origin of refugees and main countries of asylum in 2016

Source: Aksoy and Poutvaara (2019).

Reasons for emigrating and self-selection into Europe with respect to demographic characteristics

In a recent working paper (Aksoy and Poutvaara 2019) we provide the first large-scale evidence on reasons to emigrate, and the self-selection and sorting of refugees and irregular migrants for multiple origin and destination countries. We analyse data from Flow Monitoring Surveys (FMS) on nearly 22,000 refugees and irregular migrants aged 14 and over who arrived in Europe in 2015 and 2016. Once we combine FMS with Gallup World Polls and restrict our attention to nationalities with more than 100 respondents (excluding Eritrea as it is not covered by Gallup World Polls), we can study how nearly 19,000 migrants are self-selected from the source population in terms of observable characteristics and predicted income.

Figure 2 illustrates the reasons for leaving by nationality. We find that more than 90% of respondents from Afghanistan, Eritrea, Iraq, Somalia, Sudan, and Syria report leaving their country due to conflict or persecution. At the other end of the scale, a vast majority of respondents from Morocco and Algeria cite economic conditions as the main reason for leaving their home country. Limited access to basic services (such as schools and health care) or lack of food or accommodation were named as the main reason by only 3% of respondents. Overall, this suggests that the vast majority of migrants were seeking refuge from conflict or persecution, although there is a sizable population driven primarily by economic concerns.

Figure 2 Reasons for emigrating by origin country

Source: Aksoy and Poutvaara (2019).

Our analysis indicates that people who are educated to secondary or tertiary level are significantly more likely to migrate than people with lower levels of education, particularly when fleeing a major conflict. In countries with only a minor conflict or no conflict at all, the likelihood of emigration decreases with a secondary education. Thus, refugees tend to be more educated than the national average in their country of origin. There are two possible reasons for this. What has been pointed out already earlier is that better-educated individuals are in a better position to finance their trip, while liquidity constraints and immigration restrictions might prevent the poorest people from migrating. The novel mechanism that we highlight is that the risk of persecution reduces expected returns to education and that this makes the high-skilled disproportionately more likely to emigrate, even in the absence of liquidity constraints. Our model predicts that if the risk of being a victim of conflict or persecution increases, the probability of emigration becomes eventually increasing in human capital even if returns to human capital would be higher in the country of origin in the absence of conflict or persecution. As a result, it can be that refugees from a given country would be more educated than non-migrants even if economic migrants would be less educated. Empirical analysis supports our prediction.

Among men, refugees are more educated than their compatriots who did not migrate, while irregular migrants are not. Interestingly, both female refugees and irregular migrants are more educated than women who stayed. Our conjecture is that positive self-selection of female irregular migrants reflects gender discrimination that severely restricts women’s labour market options across African and Asian countries that are major sources of refugees and irregular migrants into Europe. As a result, the expected returns to women’s education may be lower in such countries than in Europe, even if income differences among men would be wider than in Europe.

We also find that refugees and irregular migrants are more likely to be single, male and young. In addition, higher levels of estimated pre-migration income strongly increase the probability of emigration – both in countries with major conflicts and in other countries, and for both men and women.

We further complement our analysis by investigating self-selection of refugees (who escaped major conflict countries) into Germany, which is the main destination country. Consistent with our main results, we find strong positive self-selection with respect to education.

Sorting of refugees and irregular migrants with respect to country characteristics

We next analyse the sorting of refugees and irregular migrants into different intended destination countries. Our main question is whether the choice of the destination country for refugees and irregular migrants is shaped by macro-level characteristics.

Migrants who are educated to primary or secondary level are more likely to head for countries that have more comprehensive migrant integration policies. They are also more likely to choose destination countries where asylum applications are considered faster and where work permit applications, once asylum has been granted, take less time to process. More generous social safety nets make a destination country more attractive for migrants with a primary or secondary education. Migrants who are educated to primary or secondary level are also more likely to choose countries that have lower unemployment rates and GDP per capita.

The role of border controls

Several policy changes, mostly tightening border controls, significantly reduced or redirected the flows of refugees and irregular migrants to affected countries. We also analyse the effect of such policies on FMS respondents’ intended destination country, using the information on the interview date.

Our results suggest that border policies significantly affected the intended destinations of refugees and irregular migrants. We find while Austria’s quota announcement and Sweden’s border controls increased the likelihood of stating “Germany” as an intended destination country, while Slovenia and FYR Macedonia’s border tightening significantly reduced intentions to migrate to Germany. In addition, both the introduction of the refugee quota by Austria and Slovenia and FYR Macedonia’s border tightening significantly increased intentions to migrate to Italy. Sweden’s border controls and Austria’s quota policies significantly reduced intentions to migrate to Sweden.

Implications

Our detailed analysis of socio-demographic characteristics and background of refugees and irregular migrants points to several policy implications. While the vast majority leave their country in order to escape conflict, the main motivation for a significant number of migrants from countries such as Algeria, Egypt, Morocco, and Pakistan is a desire to seek out better economic opportunities abroad. While most of these migrants may ultimately be denied asylum, they can slow down asylum application procedures. This may, in turn, undermine popular support for a well-managed and fair asylum system (Hatton 2017). Ageing European economies could consider tackling this problem by increasing legal employment opportunities for immigrants on a selective basis, depending on local needs. Such initiatives could form part of a broader strategy aimed at containing illegal migration to Europe (MEDAM 2018). Moreover, policies that support the integration of refugees and migrants into the labour market need to be tailored to their skills (World Bank 2018). Migrants escaping major conflicts (such as the fighting in Syria) may well benefit from receiving early access to language courses and other basic training while waiting for decisions on their asylum applications. Prompt access to employment will also help migrants to integrate better into society (OECD 2018).

References

Aksoy, C G and P Poutvaara (2019), “Refugees’ and Irregular Migrants’ Self-selection into Europe: Who Migrates Where?”, CESifo Working Paper No. 7781.

Dinas, E, K Matakos, D Xefteris and D Hangartner (2019), „Waking Up the Golden Dawn: Does Exposure to the Refugee Crisis Increase Support for Extreme-Right Parties?”, Political Analysis 27: 244-254.

Dustmann, C, K Vasiljeva and A P Damm (forthcoming), “Refugee Migration and Electoral Outcomes”, The Review of Economic Studies.

Edo, A, Y Giesing, J Öztunc and P Poutvaara (2019), “Immigration and Electoral Support for the Far-Left and the Far-Right”, European Economic Review 115: 99-143.

Halla, M, A F Wagner and J Zweimüller (2017), “Immigration and Voting for the Far Right”, Journal of the European Economic Association 15: 1341–1385.

Hatton, T J (2017), “Refugees and Asylum Seekers, the Crisis in Europe and the Future of Policy”, Economic Policy 32(91): 447-496.

MEDAM (2018), Flexible Solidarity: A Comprehensive Strategy for Asylum and Immigration in the EU – 2018 MEDAM Assessment Report on Asylum and Migration Policies in Europe, Mercator Dialogue on Asylum and Migration.

OECD (2018), Engaging with Employers in the Hiring of Refugees.

Otto, A H and M F Steinhardt (2014), “Immigration and Election Outcomes: Evidence from City Districts in Hamburg”, Regional Science and Urban Economics 45: 67–79.

UNHCR (2017) Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2016.

World Bank (2018) Asylum Seekers in the European Union: Building Evidence to Inform Policy Making.

Endnotes

[1] The 1951 Refugee Convention and its extension in 1967 define a refugee as a person who is outside his or her country of nationality “owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion,” and is unable or unwilling to return there. An irregular migrant is broadly defined as a person who travels abroad voluntarily in search of economic opportunities but has no legal right to remain in the intended destination country.