The COVID-19 pandemic led to a collapse in international trade (Baldwin 2020), as safety concerns prevented individuals from going out and consuming imported products and workers from producing for export. In the second quarter of 2020, the volume of global trade in goods fell by 12.2% and trade in services fell even more sharply, by 21.4%, compared with the last quarter of 2019. Since then, trade in goods has recovered rapidly, returning to pre-pandemic levels by October 2021, but trade in services remains well below pre-pandemic levels. This divergence between goods and services has been well documented (e.g. IMF 2021), but less well known is that there are different patterns within goods and services. Within goods, it was the trade in goods that are typically produced in GVCs, like automobiles, electronics and apparel, that fell and rebounded quickest. Within services, trade in travel services remains depressed while trade in telecommunications services is stronger than before the pandemic.

The pandemic broke old patterns

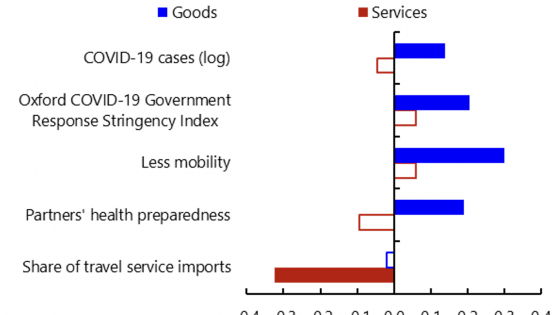

Before the pandemic, trade in goods and services closely tracked developments in aggregate demand. Import demand models, which relate a country’s imports to its domestic demand and relative import prices, were good at explaining imports of goods and services before the pandemic. However, these patterns broke down during the pandemic. In 2020, goods trade fell by less than one would have expected from changes in aggregate demand and relative import prices alone. This unexpected deviation was larger in countries with more infections, more stringent containment measures, and lower mobility (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Factors associated with the demand model’s forecast errors in 2020

Sources: Global Health Security Index; Google, Community Mobility Reports; Hale and others (2021); Our World in Data; World Trade Organization; and IMF staff calculations.

Note: The figure reports standardized coefficients of regression of residuals from the demand model on the listed variables. Solid bars show coefficients that are statistically significant at the 5 % level; hollow bars show those that are not. Trading partners’ health preparedness for the pandemic is measured by the Global Health Security Index. "Share of travel service imports" captures the share of travel services in a country's total service imports. See IMF (2022) for more details.

By contrast, services trade fell in 2020 by less than one would have expected from aggregate demand changes alone, and this gap is explained largely by the disruption to imports of travel services caused by the pandemic. These patterns could reflect a shift in spending from services to goods under pandemic waves, or they could reflect difficulties producing goods domestically under pandemic waves, in which case they are imported instead.

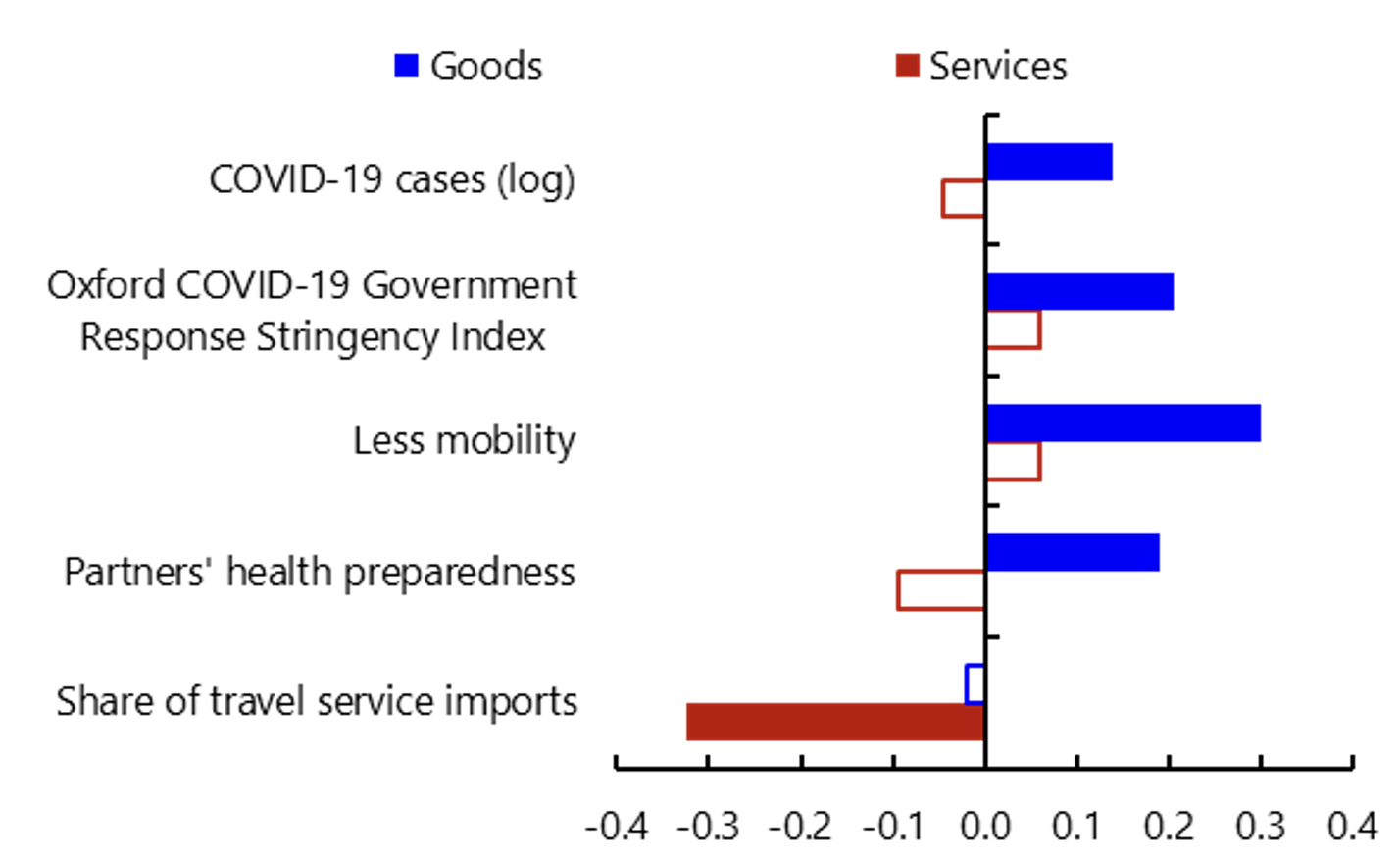

The Great Lockdown and unintended international spillovers

Another important reason for the collapse in trade in 2020 is the international spillovers from the containment policies put in place by trading partners (Bonadio et al. 2020, Espitia et al. 2021, Lafrogne-Joussier et al. 2022). Indeed, we find that as much as 60% of the drop in goods imports between January and May 2020 was the unintended consequence of lockdowns imposed by countries’ trade partners (Figure 2). This finding is based on a standard gravity model (Santos Silva and Tenreyro 2006) using detailed product-level data (‘HS-six-digit’) on bilateral goods trade that accounts for developments in importing countries and industries, including demand shifts and factors like trade agreements that could affect product-level trade between pairs of countries.

Figure 2 The international spillover effects of lockdowns

Sources: Hale and others (2021); IMF, Direction of Trade Statistics; and IMF staff calculations.

The spillovers from lockdowns depended on the country imposing them. Spillovers were less than half as large for countries whose exporting partners were more able to rely on remote working. Spillovers from lockdowns also varied over time. They strengthened between February and April as more countries outside Asia began to impose lockdowns and then started waning from May onward, suggesting that trade adapted to them.

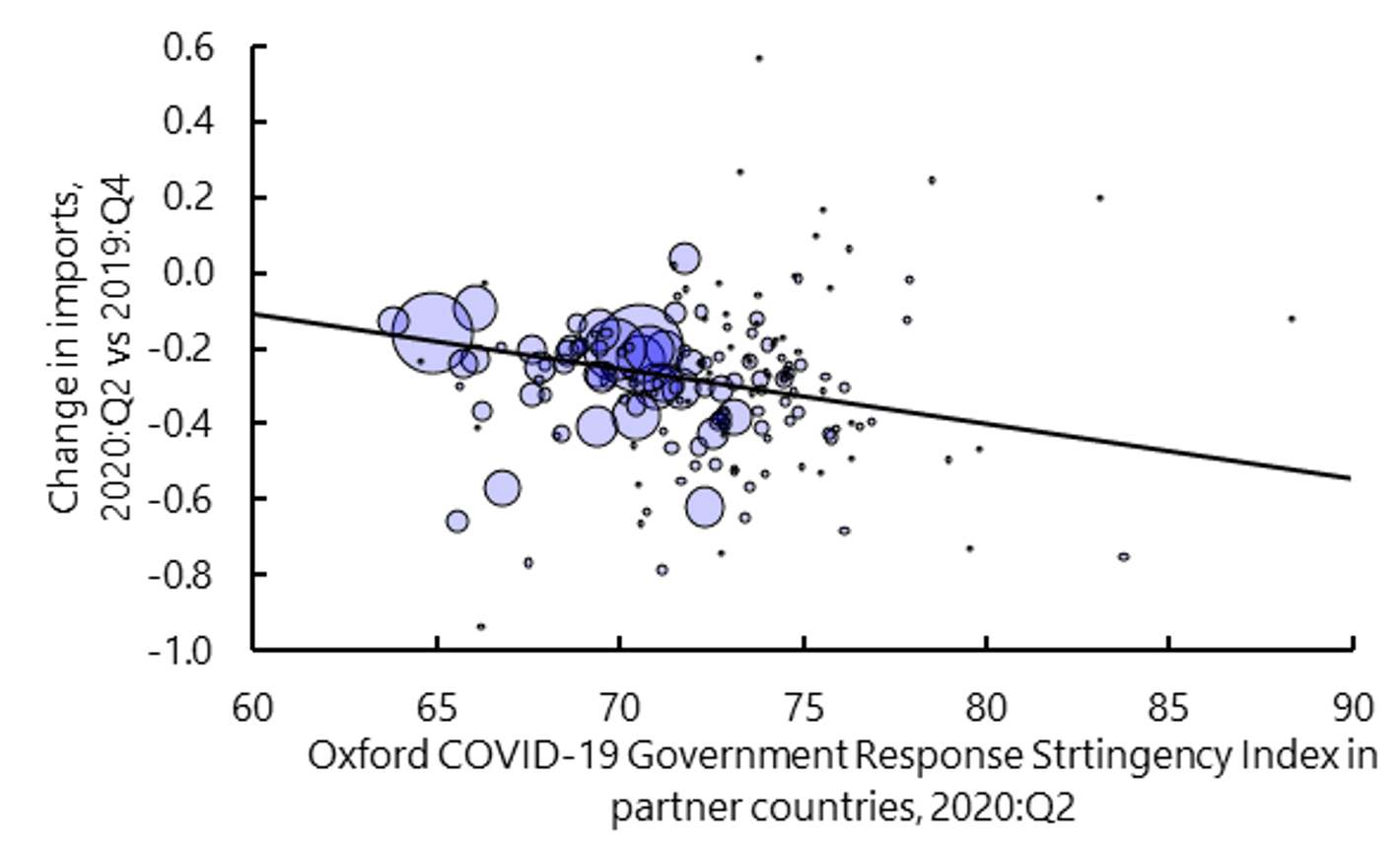

The resilience of global value chains

Like goods trade, GVCs also adapted to waves of infections during the pandemic. After containing its initial wave of infections, Asia increased its market share of GVC-intensive products. Between 2019 and June 2020, Asia increased its market share in Europe by 4.6 percentage points and in North America by 2.3 percentage points (Figure 3). The gains appear temporary, since they were pared back to 3.1 percentage points and 0.6 percentage points a year later.

Figure 3 Shifting market shares

Sources: Trade Data Monitor; and IMF staff calculations.

Note: Market shares of Factory Asia vis-a-vis Factory Europe are computed using only GVC-intensive products, as defined in the IMF (2022). GVC = global value chain. See IMF (2022) for more details.

Nevertheless, the pandemic caused widespread supply disruptions (Celasun et al. 2022) by shifting demand from services to goods while preventing workers from producing and distributing them, leading to elevated shipping costs and congested ports. The war in Ukraine has intensified these disruptions by making energy, metals, and agricultural products scarcer. Pandemics, wars, climate change, and cyberattacks prompt GVCs to become more resilient.

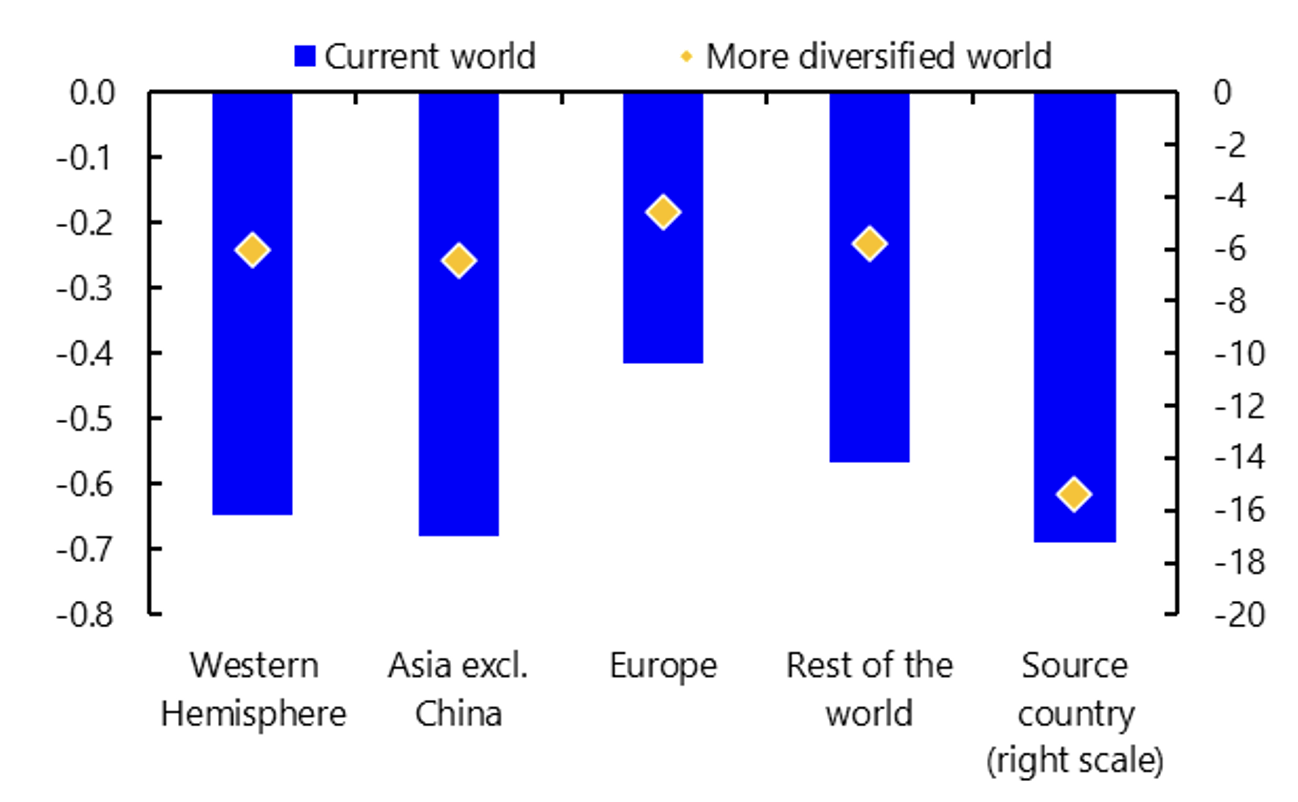

Two techniques for resilience: Diversification and substitutability

Firms can diversify their supplier relationships to source more components from different countries, which would reduce reliance on any single country (including the home country) and provide established relationships that can be tapped during a crisis (Bas and Fernandes 2022). Indeed, our simulations using a global economic model (Bonadio et al. 2021) suggest that more internationally diversified sourcing would reduce the economic impact of a supply disruption in a large supplier country by almost half in the average receiving country (Figure 4). When multiple countries are hit repeatedly by supply shocks, higher diversification reduces the volatility of economic growth by about 5%.

Figure 4 Gains from diversification

Source: IMF staff calculations.

Note: The figure shows GDP declines in response to a 25% labour supply contraction in a country that is a large global supplier of intermediates. The bars and squares show simple averages of GDP declines across countries within each region. Elasticity of substitution = 0.5. See IMF (2022) for more details.

The greatest room to diversify is to reduce the share sourced domestically. We find that firms worldwide tend to source the vast majority of their intermediate inputs in the home country (e.g. 82% in the Western Hemisphere). Reshoring would worsen this by leaving firms even more exposed to disruptions in their home country.

In addition to establishing relationships with more suppliers, firms could transform their production processes to make it easier to substitute the inputs provided by different suppliers. For example, in response to the semiconductor shortage, Tesla rewrote its software to enable it to use semiconductors that were less scarce. Our simulations with the global economic model suggest that greater substitutability can reduce the economic impact of a supply disruption in a large supplier country by around four-fifths in the average receiving country (but not in the source country).

Implications for economic policymakers

The pandemic has dramatically shaped trade developments, and through trade, it has spilled over between economies. Therefore, preserving exports and imports is one more argument in favour of ending the pandemic in all parts of the world through widespread vaccination.

Firms will ultimately decide where to produce and source inputs, but policy can also play a role given externalities and information asymmetries (Baldwin and Freeman 2022). For example, further simulations in our analysis suggest that reductions in trade costs, such as non-tariff barriers, can encourage international diversification. In addition, governments can provide information to help firms gain greater visibility into their supply chains and facilitate better risk analyses of supply chain networks.

Before the war in Ukraine, the global economy was threatened by calls for reshoring; the war has added further risk of global economic fragmentation. At the same time, it has made visible the risks of a large concentration of imports of key goods. By showing the benefits of international diversification and substitutability, our analysis underscores what can be gained by closer international integration and cooperation.

Editors' note: The views expressed in this column are those of the authors, and they do not necessarily represent the views of the International Monetary Fund.

References

Baldwin, R (2020), “The Greater Trade Collapse of 2020: Learnings from the 2008-09 Great Trade Collapse”, VoxEU.org, April 7.

Baldwin, R and R Freeman (2022), “Global supply chain risk and resilience”, VoxEU.org, April 6.

Bas, M and A Fernandes (2022), “Trade’s resilience to COVID-19”, VoxEU.org, April 26.

Bonadio, B, Z Huo, A A Levchenko, and N Pandalai-Nayar (2020), “The role of global supply chains in the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond”, VoxEU.org, May 25.

Bonadio, B, Z Huo, A A Levchenko, and N Pandalai-Nayar (2021), “Global Supply Chains in the Pandemic”, Journal of International Economics 133: 103534.

Celasun, O, N-J Hansen, M Spector, A Mineshima and J Zhou (2022), “Supply disruptions added to inflation and undermined the recovery in 2021”, VoxEU.org, March 16.

Espitia, A, A Mattoo, N Rocha, M Ruta and D Winkler (2021), “Trade and Covid-19: Lessons from the first wave”, VoxEU.org, January 18.

IMF (2021), External Sector Report, Washington, DC.

IMF (2022), "Global Trade and Value Chains During the Pandemic", in War Sets Back the Global Recovery, World Economic Outlook, April 2022.

Lafrogne-Joussier, R, J Martin and I Mejean (2022) “Supply chain disruptions and mitigation strategies”, VoxEU.org, February 5.

Santos Silva, J M C, and S Tenreyro (2006), “The Log of Gravity”, Review of Economics and Statistics 88 (4): 641–58.