Editors' note: This column is part of the Vox debate on the economic consequences of war.

As Russia’s invasion of Ukraine continues, EU policymakers are weighing more severe sanctions. At the centre of this debate is the question of whether to restrict imports of – or in the extreme case, embargo – Russian oil and gas. While many economists have focused on the effects of an embargo, Hausmann (2022) and others have argued that placing tariffs on imports from Russia instead may damage the Russian economy at much lower cost to the EU (Bachmann et al. 2022, Chaney et al. 2022, Chepeliev et al. 2022). However, the conversation about tariffs has not yet clarified a key question: Should the EU hold back from tariffs on Russian oil and gas because it depends on them?

A simple, supply-and-demand analysis of this question reveals a surprising answer. Unlike an embargo, tariffs can be designed without considering the EU’s dependence on the goods in question. This is because (a) tariffs allow EU consumers to continue buying goods if they value them enough, and (b) while tariffs do raise costs for EU consumers, they also raise revenue for the EU central budget – which can be sent back to consumers.

What matters is therefore not how reliant the EU is on Russia, but rather how reliant Russia is on the EU, since this determines how much tariffs can move the pre-tariff price at which Russia sells to the EU. To the extent that Russia depends more on the EU as a buyer of, say, natural gas, than as a buyer of goods the EU has already embargoed, a gas tariff would make a more efficient sanction from the perspective of damaging the Russian economy at the least cost to the EU.

Below, I explain these ideas through a simple, two-country model of tariffs-as-sanctions based on Sturm (2022b). Although this basic model abstracts from many important features of the debate, its main lessons apply in general, as I will discuss.

A simple model of tariff design

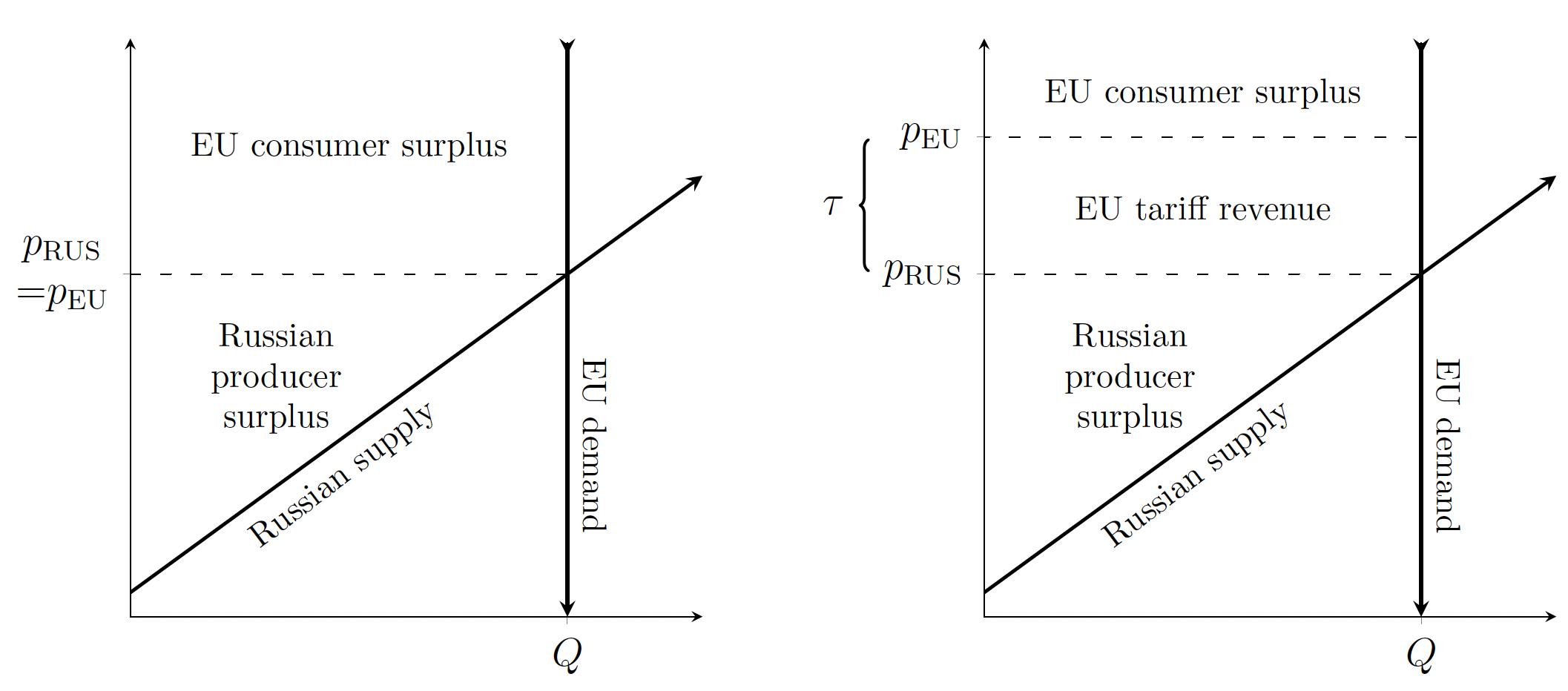

A helpful starting point is to consider the worst possible case for the EU: when EU consumers are so reliant on Russian imports that they are willing to buy them at any price. Intuitively, one might expect that tariffs are harmful to the EU in this case because EU consumers, unwilling to adjust the quantity they consume, will instead tolerate a large price increase and pay the whole tariff. Figure 1 represents this case with a completely inelastic (vertical) demand curve. In the left panel, the EU engages in free trade, whereas in the right panel it imposes a tariff on Russian imports.

The diagram shows that, because EU demand is completely inelastic, Russian producers are paid the same price whether there is a tariff or not, while a tariff increase the price faced by EU consumers one for one. However, the EU consumer’s loss is the EU central budget’s gain: tariff revenues exactly offset the loss of consumer welfare from higher prices. To the extent the EU can redistribute these revenues back to consumers, it is equally well off with or without a tariff on Russian imports. Even in the worst case, a tariff on imports from Russia is therefore ineffective, but not harmful to the EU.

Figure 1 EU-Russian import market in the case of perfectly inelastic EU demand: tariff (left panel and no tariff (right panel)

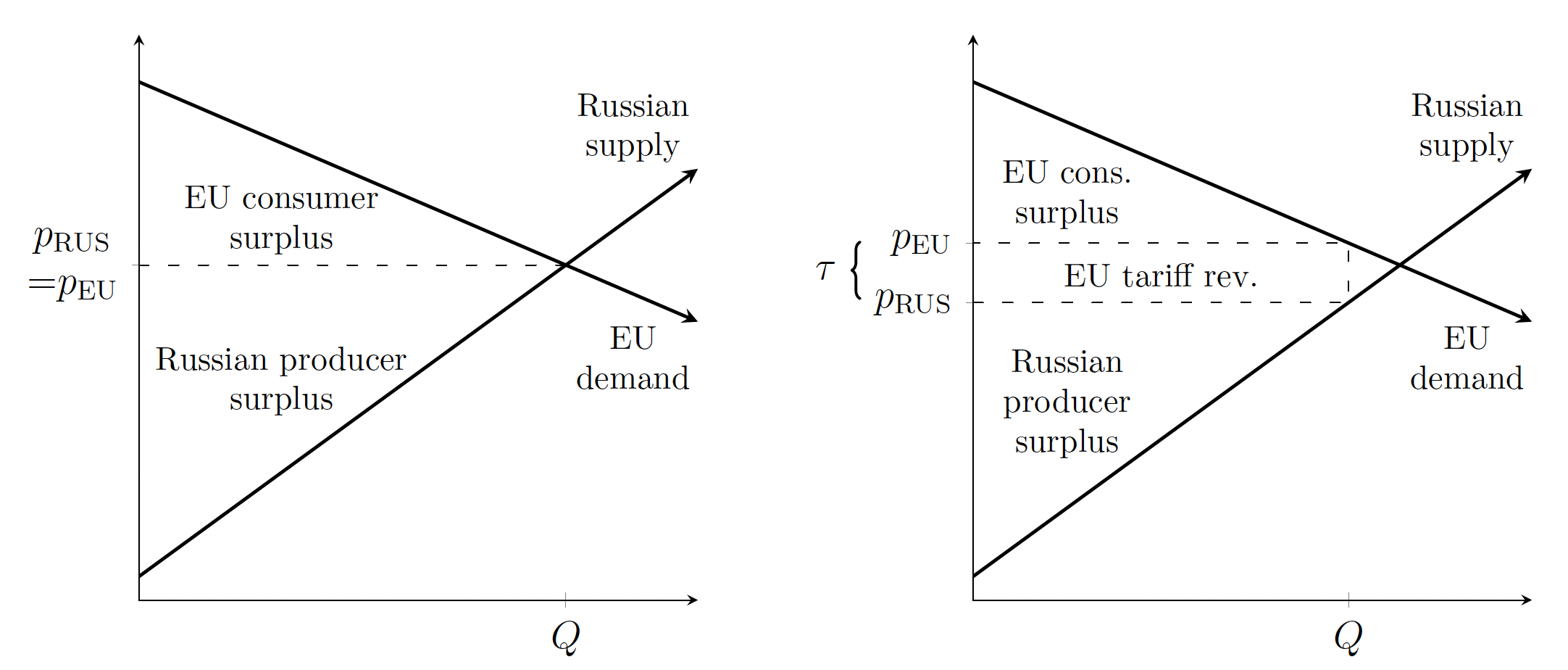

Away from the worst possible case for the EU, a tariff on imports from Russia can reduce Russian welfare while actually making the EU better off. To see why, suppose EU consumers are at least somewhat responsive to prices and consider a small increase in the EU’s tariff starting from zero, shown in Figure 2. Although a tariff still increases the price paid by EU consumers, it now also pushes down the price received by Russian producers, who are willing to supply the smaller quantity that the EU demands under a tariff at a somewhat reduced price. Because the EU now trades with Russia at a lower pre-tariff price, the tax revenue collected from the tariff is more than enough to compensate consumers for higher prices, so the EU is better off than without a tariff.1 At the same time, Russia sells a lower quantity at a lower price, and so is unambiguously worse off.

Figure 2 EU-Russian import market in the case of non-extreme elasticities: no tariff (left panel) and small tariff (right panel)

Setting the ‘optimal’ tariff

A natural question is how far the EU should go in raising such tariffs. Should tariffs be just slightly above zero, large to the point where they effectively implement an embargo, or somewhere in between? In this simple model, the answer depends on one objective parameter – the shape of Russia’s supply curve – and one political choice – the EU’s willingness to trade off economic losses at home in exchange for dealing economic damage to Russia.

The shape of Russia’s supply curve determines to what extent a tariff-induced reduction in EU demand for Russian imports pushes down the price Russian producers will accept, improving the EU’s terms of trade. This effect is the most powerful when Russian supply is inelastic, for example because it struggles to find buyers on world markets.2 Meanwhile, the EU’s ‘willingness to pay’ for economic damage to Russia determines whether it only values its own terms of trade appreciation or also values Russia’s corresponding terms of trade depreciation. If this willingness to pay is high enough, then the EU’s optimal tariff can be so large as to have the same effect as an embargo.

Notably, the EU’s dependence on a good does not directly factor into the design of its optimal tariff (Johnson 1951, Sturm, 2022a).3 This is because, unlike an embargo, a tariff does not actually prevent EU buyers from importing Russian goods, so those who depend on them can simply continue to buy them. It is true that EU buyers will face higher market prices, but higher prices for EU buyers also entail higher EU tariff revenues, which can be used to compensate the buyers. In contemplating tariffs on Russian imports, policymakers should therefore shift their focus away from the EU’s dependence on Russia as a seller, and instead target the goods for which Russia depends on the EU as a buyer. These are the goods whose Russian price the EU can most effectively depress by using tariffs to reduce its imports.

Oil and gas may well be such goods. In the case of oil, the current 30% spread between the prices of Urals (Russian) and Brent (North Sea) oil is direct evidence that trade reductions – in this case, embargoes of Russian tanker-based oil – can push down prices. In the case of gas, Russia may be even more dependent on the EU due to its reliance on pre-existing pipelines.

Beyond the competitive, two-country model

Of course, the simple analysis above abstracts from many important features of the real world.

For example, it is not only the EU who can impose trade taxes, but also Russia.4 Provided Russia does not adjust these taxes in retaliation for EU tariffs, they provide an additional motive for EU trade restrictions (Gros 2022, Sturm 2022b). However, the threat of Russian retaliation, if credible, serves as a disincentive to impose EU tariffs.

Another key factor is the role of world markets that the EU and Russia will turn to if tariffs restrict their bilateral trade. EU tariffs will shift the EU’s demand towards other buyers, typically worsening the EU’s terms of trade, but will also force Russia to incur similar costs. Unlike with Russia, the EU’s reliance on a good can impact how changes in imports affect the EU’s terms of trade on world markets, though only to the extent that EU demand moves world prices. Sturm and Menzel (2022) provide a simple test for when tariffs can still make the EU better off while hurting Russia.

Despite these complexities, the main message is clear. The EU’s dependence on Russian energy imports is not an economically sound reason to hold back from imposing tariffs. Unlike a full energy embargo, small EU tariffs on Russian energy could weaken the Russian economy while at the same time making the EU better off. While larger tariffs will come at a cost to the EU, they are likely to be more efficient than other sanctions already in place.

References

Bachmann, R, D Baqaee, C Bayer, M Kuhn, B Moll, A Peichl, K Pittel and M Schularick (2022), “What if? The Economic Effects for Germany of a Stop of Energy Imports from Russia”, ECONtribute Policy Brief 28/2022.

Chaney, E, C Gollier, T Philippon and R Portes (2022), “Economics and politics of measures to stop financing Russian aggression against Ukraine”, VoxEU.org, 22 March 22.

Chepeliev, M, H Hertel and D van der Mensbrugghe (2022), “Cutting Russia’s fossil fuel exports: Short-term pain for long-term gain”, VoxEU.org, 9 March.

Hausmann, R (2022), “The Case for a Punitive Tax on Russian Oil”, Project Syndicate, 26 February.

Johnson, H G (1951), “Optimum welfare and maximum revenue tariffs”, The Review of Economic Studies 19(1): 28–35.

Sturm, J (2022a), “A Note on Designing Economic Sanctions”, Working Paper, 16 March.

Sturm, J (2022b), “The Simple Economics of Trade Sanctions on Russia: A Policymaker’s Guide", Working Paper, 9 April.

Sturm, J and K Menzel (2022), “The Simple Economics of Optimal Sanctions: The Case of EU-Russia Oil and Gas Trade”, Working Paper, 13 April.

Gros, D (2022), “Optimal tariff versus optimal sanction: The case of European gas imports from Russia”, CEPS, 29 March.

Endnotes

1 An important practical consideration is how the EU can actually make these transfers. One approach would be to use temporary fiscal transfers to lower income households, who are more exposed to energy prices (Chaney et al. 2022).

2 Of course, our simple model does not have any ‘world markets’. Sturm and Menzel (2022) consider tariffs as a sanction in a model where the ‘rest of the world’ is a third region trading with both the EU and Russia.

3 Technically, the EU’s elasticity of demand can indirectly affect is optimal tariff if Russia’s supply curve has a non-constant elasticity. In this case, the EU’s elasticity of demand plays a role by determining at what point the supply curve is evaluated.

4 Indeed, Russia raises a substantial fraction of its federal budget through export taxes – for example, a 30% tax on gas exports – and the profits of state-owned energy companies.