Social media is playing an increasingly important role in our lives, and its political consequences are a hotly contested topic. Optimists argue that social media can empower ordinary citizens and serve as a ‘liberation technology’ (Diamond and Plattner 2010) whose use would lead to faster democratisation in authoritarian countries (Shirky 2008) and make politicians more accountable (Besley and Prat 2006). The spread of mobile phones in Africa and its effect seem to support the idea that new communication technologies can help mass political mobilisation (Manacorda and Tesei 2018).

A more pessimistic view contends that autocratic governments adjust and learn how to exploit social media to their own advantage, employing a combination of tools including online censorship, surveillance, and heavy use of online bots and trolls (Morozov 2011). In democracies, social media is often blamed for exacerbating political polarisation, spreading xenophobic ideas, and propagating fake news (Alcott et al. 2019, Tufekci 2018).

In a recent paper (Enikolopov et al. 2019), we estimate the causal effects of social media on politics in a non-democratic environment, namely, in the context of Russia in 2011–2012. After the parliamentary elections of 4 December 2011, Russia saw the largest wave of anti-government protests since the fall of the Soviet Union, with substantial geographic variation. Out of 625 cities in our sample, protests were held in more than a hundred. Exploiting quasi-random variation in the penetration across cities of the most popular social network in Russia, VKontakte (VK), we ultimately identify the causal effect of social media penetration on political protests.

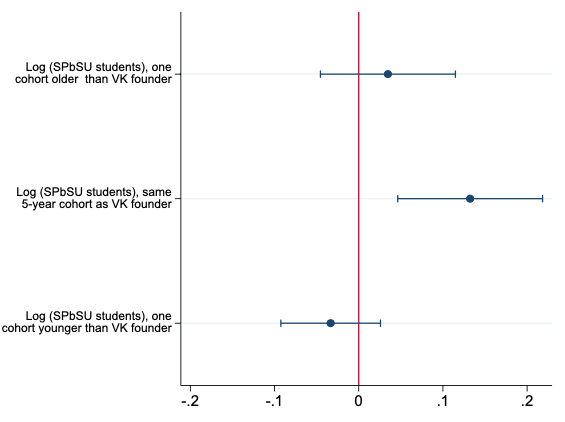

VK was created in 2006 by Pavel Durov, a student of Saint Petersburg State University. This online social network, analogous to Facebook in functionality and design, was the first mover in the Russian market and secured its dominant position with a user share of over 90% by 2011. Initially, users could only join the platform by invitation through the Saint Petersburg State University’s student forum, which was also created by Durov. As a result, the vast majority of VK’s early users were Durov’s fellow students. This, in turn, made friends and relatives of these students more likely to open an account early on. Since the university attracted students from across the country, this sped up VK’s propagation in the cities where these students came from. Thus, the idiosyncratic variation in the distribution of Durov’s classmates’ home cities had a long-lasting effect on VK penetration (Figure 1).

Figure 1 VK penetration in 2011 among Saint Petersburg State University student cohorts

Next, we show that fluctuations in the student flow from Russian cities to Saint Petersburg State University over time predict the probability of protests, which took place in December 2011 (Figure 2), and protest participation. In an instrumental variable framework, we find that, on average, a 10% increase in VK penetration leads to a 4 percentage point higher chance of a protest taking place and a 19% larger protest. As a falsification test, we show that VK penetration in 2011 did not predict higher protests before VK was created in respective cities (e.g. protests in the USSR in the late 1980s).

Figure 2 Incidence of protests in 2011 and Saint Petersburg State University student cohorts

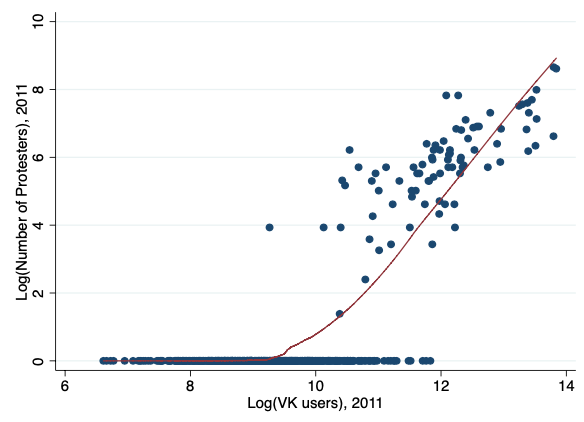

Non-parametrically, we document that there exists a threshold of VK penetration below which there is no relation between VK penetration and protests (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Nonparametric relationship between VK penetration and number of protesters

We highlight two channels through which social media could lead to protest participation in a non-democracy.

- On the one hand, social media’s low barriers to entry make it much more difficult for the regime to limit the spread of potentially harmful information that could lead to more anti-government sentiments in the population. We call this the information channel.

- On the other hand, the fact that social media relies on user-generated content facilitates horizontal information flows, which could lower the costs of coordination and thus alleviate the collective action problem (Ostrom 1990). We call this the coordination channel. If this channel is at work, the chances that people take to the streets could go up even if the number of individuals in opposition does not increase. In our context, VK was used heavily for tactical coordination of protests in Russia in 2011–2012. For instance, for almost every city with a protest, activists created VK protest communities, where people could exchange logistical details.

We find no evidence that the information channel is at work in our context. In particular, we study VK’s impact on pro-government vote and attitudes toward the regime and find that VK led to a higher – not lower – pro-government vote consistently across all elections after the creation of the social network. In an extensive survey conducted just a couple of weeks before the protests broke out, we find that VK penetration led to a more favourable opinion of Putin and the government overall and lower stated willingness to participate in a hypothetical protest. We also do not find any evidence for increased political polarisation since there was no jump in negative attitudes toward the regime or in the opposition vote. Finally, we analyse the political content on VK and find that, on average, it was neutral or positive toward the government.

However, we do find evidence in favour of coordination. The number of VK users in online protest communities was positively associated with the incidence and the size of the protests. We also find that the effect of social media on protests was stronger in larger cities, where logistical coordination tends to be more critical. Finally, we show that protests tend to be smaller in cities where, conditional on the total number of social media users, the user base was more fractionalised between Facebook and VK. A more divided user base matters because it may lead to less horizontal information flows between users of different social networks and, as a result, more difficult logistical coordination. These findings may also be consistent with the importance of peer pressure and social image, and we explore this hypothesis further in a companion project (Enikolopov et al. 2017).

Overall, our paper provides evidence that social media penetration had a causal effect on both the incidence and the size of the demonstrations in Russia in December 2011. Additional evidence suggests that social media affects protest activity by reducing the costs of collective action, rather than by spreading information critical of the government or by increasing political polarisation. Thus, our results imply that social media induce coordination and alleviate the collective action problem.

While our results confirm the earlier claims of the digital optimists, we note that these results may not generalise to other settings. The Russian protests of 2011 were unexpected, and the government did not have time to prepare for them. If a government is aware of the effects of social media on political protests, it may counteract them by censoring online content related to collective action (King et al. 2014, Ananyev et al. 2019) or by manipulating the information in social media (King et al. 2017). Furthermore, the reduction in coordination costs can also have its dark sides – for example, possibly leading to more extremism and hate crimes (Bursztyn et al. 2019). More research is needed to understand whether similar results hold for other outcomes and in different contexts.

References

Allcott, H, L Braghieri, S Eichmeyer and M Gentzkow (2019), “The welfare effects of social media”, working paper.

Ananyev, M, D Xefteris, G Zudenkova, and M Petrova (2019), “Information and communication technologies, protests, and censorship”, working paper.

Besley, T, and A Prat (2006), “Handcuffs for the grabbing hand? Media capture and government accountability”, American Economic Review 96(3): 720–36.

Bursztyn, L, G Egorov, R Enikolopov, and M Petrova (2019), “Social media and xenophobia: Evidence from Russia”, working paper.

Diamond, L, and M Plattner (2010), “Liberation technology”, Journal of Democracy 21: 69–83.

Enikolopov, R, A Makarin, M Petrova and L Polishchuk (2017), “Social image, networks, and protest participation,” working paper.

Enikolopov, R, A Makarin and M Petrova (forthcoming), “Social media and protest participation: Evidence from Russia“, Econometrica.

King, G, J Pan and M E Roberts (2014), “Reverse-engineering censorship in China: Randomized experimentation and participant observation”, Science 345(6199): 1–10.

King, G, J Pan and M E Roberts (2017), “How the Chinese government fabricates social media posts for strategic distraction, not engaged argument”, American Political Science Review 111(3): 484–501.

Manacorda, M, and A Tesei (2018), “Liberation technology: Mobile phones and political mobilization in Africa”, working paper.

Morozov, E (2011), The net delusion: The dark side of internet freedom, Cambridge, MA: Perseus Books.

Shirky, C (2008), Here comes everybody: The power of organizing without organizations, London: Penguin Books.

Tufekci, Z (2018), “How social media took us from Tahrir Square to Donald Trump”, MIT Technology Review.