Subnational governments (SNGs) are key players in the design and implementation of policies across the globe, and thus have played a crucial role in tackling the COVID-19 crisis. On average, SNGs in OECD countries are responsible for 33%, 26% and 18% of the central government’s expenditure1 on health,2 public order and safety and social protection, respectively. In some countries this responsibility is even heavier, as SNGs can be responsible for more than half of all social protection (e.g., Denmark) and more than 80% of all health (e.g. Denmark, Spain, Sweden and Switzerland) and public order and safety (e.g., Australia, Germany, Switzerland and the United States) expenditure.

Not only have SNGs been in the forefront of the crisis, but they also are key players in the economic recovery – they are responsible for almost two-thirds of all public investments made in OECD countries. Nevertheless, SNGs have a tendency towards pro-cyclical policymaking (OECD 2013). That is because they have rigid budgets, and, thus, when facing fiscal constraints, opt to cut discretionary expenditures, which includes investment.

This budget rigidity is common in the intergovernmental fiscal systems of OECD countries. First, SNGs have limited autonomy to increase revenues, as they are typically dependent on intergovernmental grants and rarely have full discretion over their tax policies (Dougherty et al. 2019). Second, they have to comply with a wide range of fiscal rules and face institutional borrowing constraints (OECD 2021). Third, even without borrowing restrictions, SNGs have less developed and more illiquid bond markets in comparison with national bond markets. As a result, they cannot easily roll-out debt or compensate for revenue shortfalls by issuing debt, as central governments do. Cutting discretionary spending such as investment often becomes the easiest path to adjust their budgets.

The combination of SNGs (1) having substantial responsibility in health, social protection and public order and safety, (2) having rigid budgets, and (3) being responsible for the majority of public investment makes SNG finances critical in the context of the COVID-19 crisis. The COVID-19 crisis brought the necessity to spend on containment measures, treatment of the sick and social protection programmes, at the same time as it affected economic activity and, thus, tax revenues. Although these expenditures are necessary, a fragile subnational fiscal position may lead to pro-cyclical fiscal policy in the future, delaying economic recovery and reducing growth as a result of smaller public investments, as happened in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC).

In this column, we explore how the COVID-19 crisis might impact the fiscal position of SNGs and argue that because recurrent taxes on immovable property, which tend to relatively stable, represent a higher share of SNGs’ revenues than those of central governments, and since central governments provided substantial fiscal support to SNGs, SNGs’ fiscal positions will likely not be heavily impacted by the pandemic, as they were in the GFC. And thus, we might not face a drought in public investment following the COVID-19 crisis, at least on the scale of the reduction prompted by the GFC.

Subnational tax revenues tend to be more stable than those of central governments

Owing to tax competition at the subnational level and to economies of scale in tax collection at the central level, SNGs tend to have a less diversified tax mix in comparison to central governments (OECD 2013). SNGs in most OECD countries tend to rely on property taxes, which, on average, represent 39% of their tax revenues. Of these revenues, an average of 83% comes from recurrent taxes on immovable property and in 20 out of 37 OECD countries,3 this ratio is higher than 95%. In contrast, taxes on property represent less than 2% of central governments’ tax revenues, as central governments tend to rely more on goods and services taxes. Other, less wide differences in tax composition across levels of government concern personal and corporate income taxes – the former represents a greater portion of SNGs tax revenues in comparison to tax revenues from the central government and social security funds. Panel A of Figure 1 summarises these differences.

Figure 1 Tax revenue structure and buoyancy across levels of government (average values in OECD countries)

Notes: PIT, CIT, SSC and VAT/GST stand for personal income tax, corporate income tax, social security contributions and goods and service tax (i.e., value added tax), respectively. The dark-blue column shows the difference of the buoyancies between the central government (CG) and SNGs. Social security funds were aggregated at the central government level. Buoyancies were calculated using an error correction model with a dummy for negative GDP growth and panel data from 1990 to 2019. There is no country in which SNGs rely substantially on SSC and, therefore, only the buoyancy for the CG is shown. Panel A: Short-term buoyancy for each type of tax was computed using the mean group estimator. Panel B: Short-run buoyancy as of 2019 or closest year with data available.

Source: OECD Revenue Statistics and Dougherty & de Biase (2021).

These differences in tax structure are particularly relevant, as the responsiveness of tax revenues to economic activity varies depending on the tax. Since recurrent taxes on immovable property are commonly levied on property capital, they will follow the short-term deviations in economic activity if house prices are unaffected. As a result, SNGs’ property tax revenues are the least buoyant4 of all types of taxes, with an average short-term buoyancy of 0.7 (i.e. for a GDP growth rate of 1%, SNGs’ property tax revenues will increase in the short term by 0.7%). It is also worth noting that this crisis was not caused by a housing crisis, as was the case for the GFC, and therefore house prices are not expected to fall (they are actually increasing in many OECD countries). Central governments’ property taxes are substantially more buoyant as recurrent taxes on immovable property represent only 13% of all central governments’ property tax revenues, with the majority of central property tax revenues coming from taxes on capital and financial transactions (47% of central governments’ property tax revenues). Panel B of Figure 1 shows tax buoyancy by tax type.

Central governments provided generous support to subnational governments

Due to the vulnerability of SNGs to liquidity crises and to the potential impact of such crises on the ability of SNGs’ to take the necessary measures to contain COVID-19 and save lives, central governments have stepped in to support SNGs. In a survey by the OECD Network of Fiscal Relations across Levels of Government,5 OECD members and partner countries reported that the most common response from central governments has been the provision of extraordinary grants (14 of 23 countries). Eight countries temporarily lifted fiscal rules and five countries’ central governments provided additional loans and guarantees to SNGs. It is worth noting that in those countries that provided monetary support to SNGs, the support also involved extraordinary grants. In other words, even in cases in which the central government offered guarantees and loans to provide liquidity to SNGs, these measures were made in combination with the provision of grants. Figure 2 summarises the result of the survey.

Figure 2 Measures employed by central governments to improve subnational fiscal capacity in 2020.

Source: Based on the COVID-19 Rapid Survey held by the OECD Network on Fiscal Relations across Levels of Government.

This practice of providing liquidity to SNGs is not uncommon in times of crisis. Central governments from at least nine OECD countries also provided support to SNGs through grants6 in the GFC. Nevertheless, there is a substantial difference in the nature of this support that is worth mentioning. In the COVID-19 crisis, the amount of funds granted to SNGs was defined at the start of the crisis, as the purpose of the support was to provide the necessary fiscal capacity for SNGs to contain the virus and treat the ill, while in the GFC, the support was provided later, as a part of economic stimulus packages. Thus, one of the main differences between these grants is that intergovernmental grants in the GFC were mostly earmarked for investment purposes, while funds provided to tackle the COVID-19 were mostly non-earmarked.7

Another key difference regards the fact that during the GFC, funds were provided based on the necessity to boost economic recovery, while the criteria to define the amount of funds transferred in the COVID-19 crisis were mostly based on an expectation of the impact of the crisis on subnational revenues and expenditures. At the time that these grants were designed, the death toll was rising substantially, along with a rapid and unparalleled increase in unemployment, generating a deep reduction in economic activity. Forecasts were, hence, very pessimistic (Clemens and Veuger 2020) and all but two OECD and partner countries were expecting the fiscal position of SNGs to deteriorate (Dougherty et al. 2020). Thus, intergovernmental grants provided to tackle the COVID-19 crisis were designed under deep uncertainty and with the goal to provide the necessary fiscal capacity to tackle an unmatched downswing caused by a deadly pandemic.

Current and future prospects of subnational finances

Surprisingly, early data on the government revenues and expenditures across levels of government suggest that SNGs’ fiscal positions were not heavily impacted by the COVID-19 crisis as expected by previous papers (Clemens and Veuger 2020) or in comparison to the expected decrease in GDP caused by the COVID-19 crisis (Chudik et al. 2020). In some countries, SNGs are better-off financially now than they were in 2019. Central governments have absorbed most of the shock.

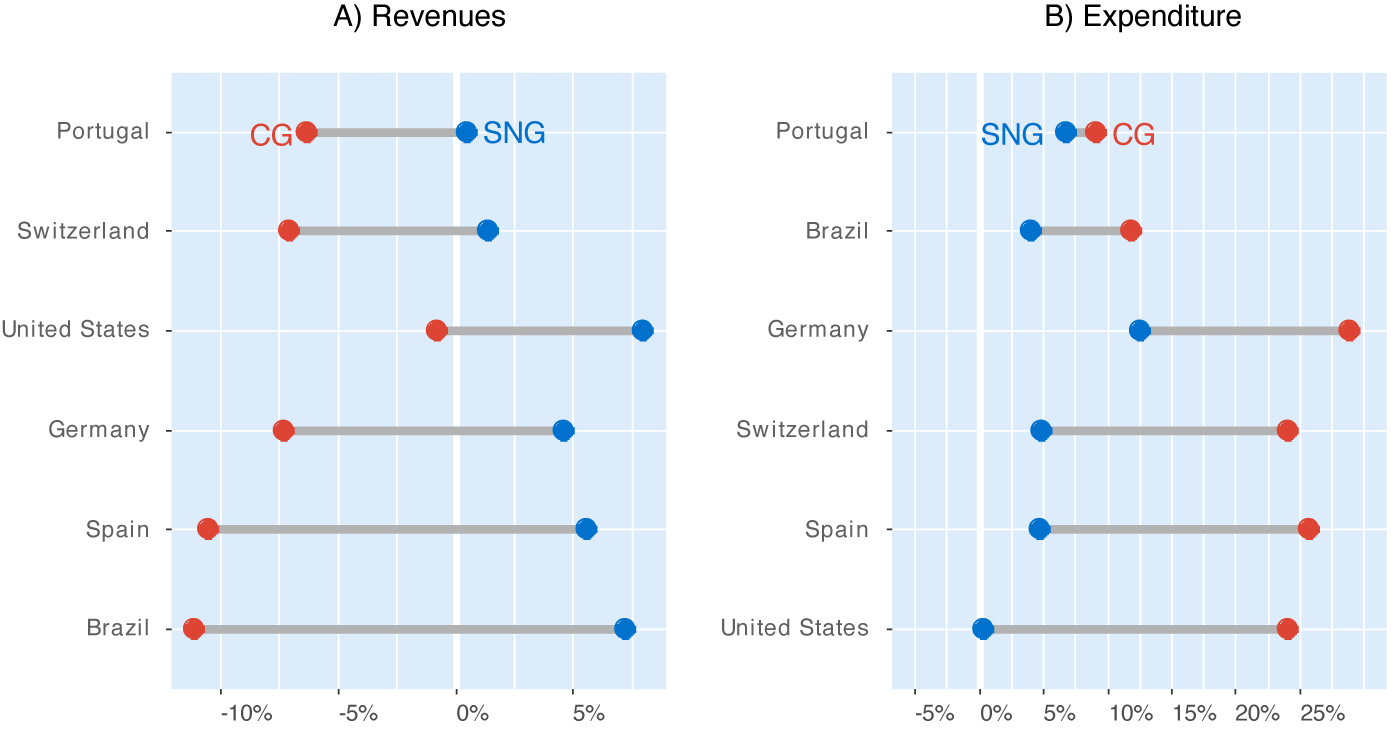

In a sample of six countries with early national data available, the average increase for SNG revenues was 5% while central governments experienced a decrease in revenues of 7% on average (Figure 3). In the aggregate, in none of these six countries did SNGs experience a reduction in revenues, while in all of them, central governments experienced a reduction in revenues. On the expenditure side, in aggregate for the six countries, both SNGs and central governments saw their expenditures increase, but the increase was larger for central governments. Early unconsolidated national accounts data suggest that this broad pattern is likely to be representative of most OECD countries’ experiences.

Figure 3 Nominal growth of revenues and expenditures of different levels of government between 2019 and 2020

Note: Ordered by the difference between central government and SNGs.

Source: Annex to Dougherty & de Biase (2021).

This surprising fiscal performance of SNGs in 2020 might help to avert the slowdown in subnational public investment that happened in the aftermath of the GFC, leading to a more rapid economic recovery following this crisis. It is also worth mentioning that this crisis was not caused by a housing crisis and, therefore, we should not expect a fall of housing prices as happened in the GFC, which affected property tax revenues.

Nonetheless, it is worth highlighting that this positive outlook remains uncertain. Many intergovernmental grants are based on tax revenues collected in previous year(s) and therefore affect SNGs with a lag. In this case, part of the drop in revenues that central governments absorbed in 2020 may be transferred to SNGs in the form of lower intergovernmental grants in this and following years, or greater future grant conditionality (de Mello and Jalles 2020). In addition, this crisis was very asymmetric (Allain-Dupré et al. 2021) and, therefore, although the aggregate situation of SNGs seems to be better than expected, some jurisdictions experienced a more acute crisis and will likely engage in fiscal consolidation, leading to pro-cyclical policy that may reduce the pace of economic recovery. This would exacerbate the asymmetric impact of the COVID-19 crisis, leading to substantial regional asymmetries within countries and, potentially, increasing income inequality.

Authors’ note: The views expressed in this column are those of the authors and they do not necessarily represent the views of the OECD.

References

Allain-Dupré, D, I Chatry, V Michalun and A Moisio, (2021), "The territorial impact of COVID-19: managing the crisis across levels of government," OECD Tackling Coronavirus, May.

Chudik, A, K Mohaddes, M H Pesaran, M Raissi and A Rebucci (2020), "Economic consequences of Covid-19: A counterfactual multi-country analysis," VoxEU.org, 20 October.

Clemens J and S Veuger (2020), "Fiscal federalism and the COVID-19 shock in the US," VoxEU.org, 28 September.

Dougherty, S and P Biase (2021), "Who absorbs the shock? An analysis of the fiscal impact of the COVID-19 crisis on different levels of government", International Economics and Economic Policy.

Dougherty, S, M Harding and A Reschovsky (2019), "Twenty years of tax autonomy across levels of government : measurement and applications," OECD Working Papers on Fiscal Federalism, 29.

Dougherty, S, C Vammalle, P De Biase and K Forman (2020), "COVID-19 and fiscal relations across levels of government," OECD Tackling Coronavirus, July.

de Mello, L and J Jalles (2020), "The global crisis and intergovernmental relations: centralization versus decentralization 10 years on," Regional Studies 54.

OECD (2013), Fiscal Federalism 2014: Making Decentralisation Work, OECD Publishing.

OECD (2021), Fiscal Federalism 2022: Making Decentralisation Work, OECD Publishing, forthcoming.

Endnotes

1 OECD System of National Accounts as of 2019 – data is unconsolidated. Selected data for several large countries show that consolidated data are broadly consistent with these findings (see Dougherty and de Biase, 2021).

2 When considering expenditures related to public health services, such as immunisation programmes, the average share of public expenditure that comes from SNGs is 40%, even greater than the share for health, and can reach 100% in some countries.

3 Only countries with data available in OECD Revenue Statistics. Values of 2019 of the closest year.

4 Tax buoyancy refers to the responsiveness of tax revenues to a 1% movement in the GDP – it differs from tax elasticity by not controlling for tax changes.

5 The COVID-19 survey, done in June of 2020, received twenty-three replies from OECD and partner countries. This sample consists of a variety of countries from five continents that differ substantially in size, demography and socioeconomic factors.

6 Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Japan, Korea, Norway, Portugal and Spain.

7 There usually were, though, addition requirements related to transparency and accountability of the use of the funds (Dougherty et al. 2020).