Firms in emerging markets rely heavily on dollar funding, often obtained as loans from foreign banks. This means that US monetary policy directly affects their credit conditions. When interest rates in the US fall, emerging market firms can borrow more at lower interest rates (Lee et al. 2019, Ivanshina and Braeuning 2019, Peydro et al. 2019, Temesvary et al. 2018).

US banks are not the only ones providing international credit, but they are key players in this market. Loan-level data collected as part of the Federal Reserve’s stress tests suggest that the largest US banks lend around $100 billion in new loans to emerging markets each year, roughly 15% of the banks’ total corporate and industrial loan origination. US banks are significant local players In Latin America, particularly Mexico.

Expanded lending to emerging market economies in response to accommodative US monetary policy

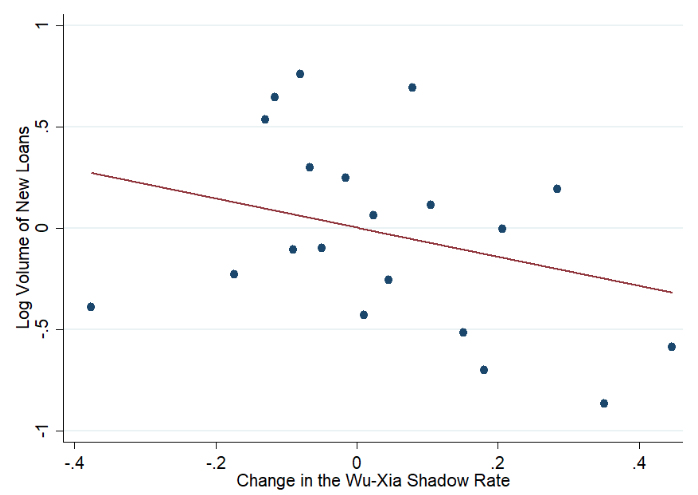

Figure 1 plots the monthly log volume of new loans to emerging market firms by US banks, against the Wu-Xia shadow rate from January 2012 to November 2015.1

Figure 1 The relationship between changes in the stance of US monetary policy and US bank lending to emerging markets, 2012–2015

Source: Liu et al. (2020).

Note: The scatterplot groups changes in the Wu-Xia Shadow rate into equal-sized bins, showing the mean of this change and the mean log lending volume to emerging market borrowers in each bin. The log volume of new loans is observed by bank and month. Log lending volumes shown are residuals from a regression of each bank’s monthly lending volume to emerging market borrowers on bank-fixed effects.

The negative relationship in the figure shows that US banks lent more to emerging market borrowers when US monetary policy eased. A 10 basis point reduction in the Wu-Xia shadow rate led to a 6.5% increase in a bank’s loan originations. The positive relationship between new lending and US monetary easing only holds for lending to emerging markets, not for lending to the US or other advanced economies. In addition, this relationship is only present during the zero lower bound period, and not after 'lift-off'.2

Transmission of US monetary policy to emerging markets was limited to banks that performed well in the US stress tests. The Federal Reserve tests the largest banks in the US take annually. In its Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review (CCAR), the Federal Reserve projects each bank’s Tier 1 capital ratio under several scenarios, including a severely adverse scenario. Banks are expected to maintain a Tier 1 capital ratio of at least 4.5% in all projected quarters and scenarios.3 If a bank’s capital ratio falls below the required minimum threshold, any distribution of capital is subject to additional regulation. For example, dividend payouts would be subject to approval by the Federal Reserve.

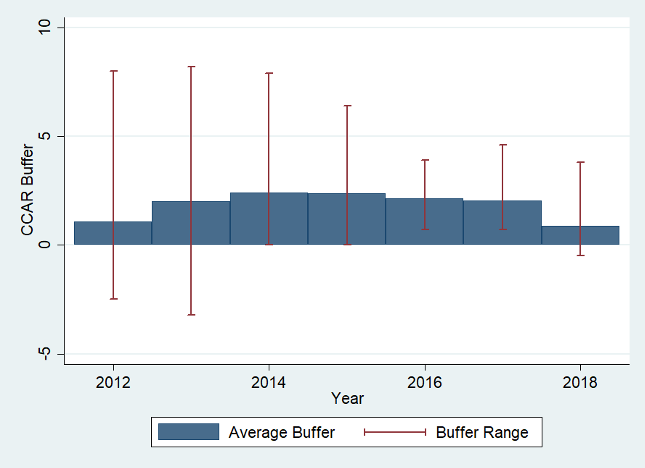

For our analysis in Liu et al. (2020), we obtain each tested bank’s minimum Tier 1 capital ratio in the severely adverse scenario and deduct from it the minimum threshold applicable in the corresponding year. We term this difference the CCAR buffer. Figure 2 shows the yearly distribution.

Figure 2 US bank stress test results over time

Source: Liu et al. (2020).

Note: The bars in the figure show the participating BHCs’ mean CCAR buffers by year. The red lines shows the range of CCAR buffers.

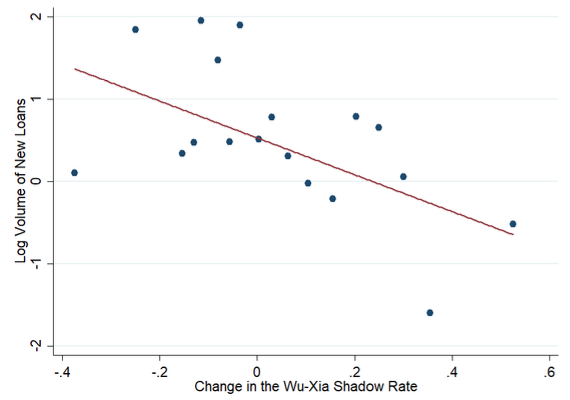

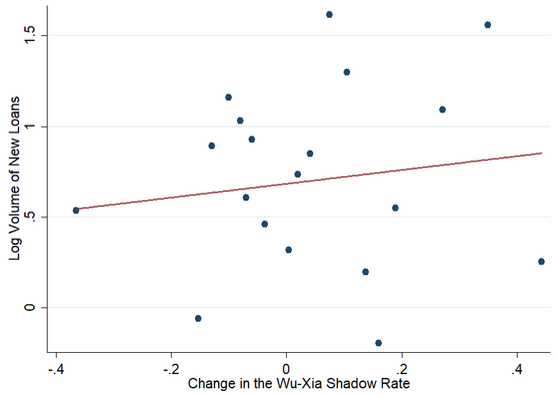

Figure 3 shows the relationship between bank log lending volumes to emerging markets and, separately, changes in the Wu-Xia shadow rate for banks with good and bad stress test performances. Good performers (left panel) are banks with CCAR buffers of at least 2%, while bad performers are banks with buffers below 2%. Only good performers expanded their lending when monetary policy eased, while bad performers left their lending unchanged.

Figure 3 The relationship between changes in the stance of US monetary policy and US bank lending to emerging markets for banks with good and bad performances in the stress tests

a) CCAR buffer ≥ 2%

b) CCAR buffer < 2%

Source: Liu et al. (2020).

Note: The scatterplot groups changes in the Wu-Xia Shadow rate into equal-sized bins, showing the mean of this change and the mean log lending volume to emerging market borrowers in each bin. The log volume of new loans is observed by bank and month. Log lending volumes shown are residuals from a regression of each bank’s monthly lending volume to emerging market borrowers on bank-fixed effects. Observations in the left panel have a CCAR buffer of at least 2%, while observations in the right panel have CCAR buffers below 2%.

Conclusions

Our results have several implications.

Bank capital positions determine the effectiveness of monetary policy, as discussed in Kashyap and Stein (1994), Peek and Rosengren (1995), Peek and Rosengren (2013), and Van den Heuvel (2002). When banks are capital constrained, they have no room to expand lending when monetary policy loosens. Consistent with this view, we find that stress test results only affected the transmission of monetary policy when there was easing. In contrast, banks’ responses to tightening US monetary policy were more homogenous.

Domestic regulation and supervision can influence the extent to which domestic monetary policy is transmitted across borders. There has been much debate about the potential undesirable effects of advanced economy monetary policy for emerging markets, and how emerging markets may be able to prevent or limit spillovers through capital controls, macroprudential policy or their own monetary policy. But, as our research shows, advanced economies themselves can reduce spillovers through domestic regulation and supervision.

Finally, our results highlight cross-border spillovers from local supervision and regulation. US stress tests reduced lending within the US (Acharya et al. 2018, Cortes et al. 2018), but when banks operate internationally, these contractionary effects of US stress tests on lending do not stay within borders.

References

Acharya, V V, A N Berger, and R A Roman (2018), "Lending implications of US bank stress tests: Costs or benefits?", Journal of Financial Intermediation 34: 58 – 90.

Bräuning F, V Ivashina (2020), "US monetary policy and emerging market credit cycles", Journal of Monetary Economics, forthcoming.

Cortes, K, Y Demyanyk, L Li, E Loutskina, and P E Strahan (2018), "Stress Tests and Small Business Lending", NBER working paper 24365.

Kashyap, A K and J C Stein (1994), "Monetary policy and bank lending", in N G Mankiw (ed), Monetary policy, University of Chicago Press: 221–261.

Lee, S J, L Qian Liu, and V Stebunovs (2020), "Risk-Taking Spillovers of US Monetary Policy in the Global Market for US Dollar Corporate Loans", Journal of Banking and Finance, forthcoming.

Liu, E, F Niepmann, and T Schmidt-Eisenlohr (2020), "The Effect of US Stress Tests on Monetary Policy Spillovers to Emerging Markets", CEPR Discussion Paper 14128.

Morais, B, J-L Peydro, J Roldan-Pena, and C Ruiz-Ortega (2019), "The International Bank Lending Channel of Monetary Policy Rates and QE: Credit Supply, Reach‐for‐Yield, and Real Effects", The Journal of Finance 74(1): 55-90.

Peek, J and E Rosengren (2013), "The role of banks in the transmission of monetary policy", Federal Reserve Bank of Boston public policy discussion Paper 13-5.

Peek, J, and E Rosengren (1995), "Bank lending and the transmission of monetary policy", Conference Series – Federal Reserve Bank of Boston (39): 47-68.

Temesvary, J, S Ongena, and A L Owen (2018), "A global lending channel unplugged? Does US monetary policy affect cross-border and affiliate lending by global US banks?", Journal of International Economics 112: 50–69.

Van den Heuvel, S (2002), "Does bank capital matter for monetary transmission?", Economic Policy Review 8(1): 259–265.

Endnotes

[1] The Wu-Xia shadow rate is a measure of changes in the stance of US monetary policy during the zero-lower bound period, when the Fed kept the Fed Funds rate close to zero and engaged in quantitative easing. Note that figure 1 groups observations into bins to make the result more visible. In addition, log lending volumes shown are deviations from each bank’s mean lending to emerging markets.

[2] The rise in the Feds Fund rate on 12 December 2015 has been referred to as the 'lift-off'.

[3] Before 2016, BHCs were expected to maintain a Tier 1 capital ratio of at least 5% in all scenarios.