The US government is so concerned about the US dollar that on June 3 it broke from standard operating procedure and had the chairman of the Federal Reserve Board speak about the dollar (a role previously reserved for the US Treasury Secretary and occasionally the President). The dollar immediately strengthened and some analysts predicted that the dollar’s relentless depreciation since its peak in February of 2002 was finally over. Some even predicted a dollar appreciation over the next year (at least versus the Euro and other flexible currencies). On June 6, however, the dollar took another dive and fears resurfaced that the dollar’s depreciation had further to go. Secretary Paulson responded on June 9 by stating in a CNBC interview that he “would never take intervention off the table” to support the dollar.

What will it take?

In order for the dollar to stabilize, the US will need to attract enough capital at existing prices to not only finance its current account deficit, but also to balance capital outflows by US citizens (which increased by over 100% from 2005 to $1.21 trillion in 2007). Figure 1 shows the countries with the largest holdings of US portfolio liabilities (equities and debt) as of June 30, 2007.

Figure 1 Foreign holdings of US portfolio liabilities (30 June 2007)

Notes: Based on US govt. data 'Report on Foreign Portfolio Holdings of US Securities'. Includes official and non-official sector holdings.

*Bahrain, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Oman, Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates.

Will foreigners continue to add to their holdings of US assets? This is the greatest vulnerability to not only the dollar, but also the existing system of large global imbalances. Rough estimates suggest that despite the reduction in the US current account deficit, the US will require an additional $1.8 to $2.7 trillion of foreign investment in just 2008.1 This is in addition to the (roughly) $16 trillion that foreigners already hold.2 Will foreigners invest these massive sums of money at current exchange rates? What will be the effect of increased regulation in US markets and perceived hostility in some sectors to foreign investment?

How have foreigner done on their US investments?

These questions are particularly pressing given the disappointing returns that foreigners have recently earned in the US. Evidence shows that investors tend to “chase returns”—i.e., increase investment in assets and countries that have recently had higher returns and vice versa.3 But from 2002 through 2006—before the recent turmoil in US financial markets—foreigners earned an average annual return of only 4.3% on their US investments, while US investors earned a much more impressive 11.2% abroad.4

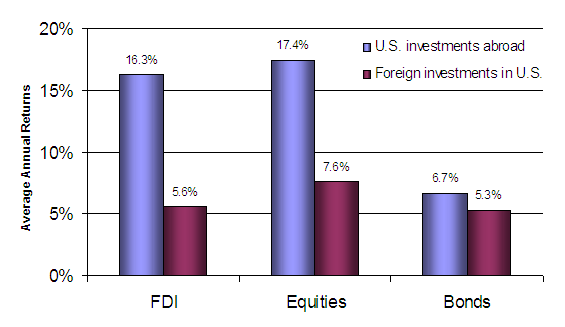

This lower rate of return for foreigners investing in the US persists even after removing official sector investment (as much as possible given data limitations) and focusing only on the private sector.5 As shown in Figure 2, this pattern even persists for investment within specific assets classes—equities, foreign direct investment, and, to a lesser extent, bonds. For example, foreigners earned an average annual return of only 7.6% on their US equity holdings from 2002 through 2006, while US investors earned 17.4% on their foreign equities. These patterns also persist (although to a lesser extent) after removing the effect of the dollar’s depreciation and making rough adjustments for risk.

Figure 2 Returns on private sector investment positions, 2002-6

Other Potential Reasons to Invest in the US

Are there reasons why foreigners would invest in the US even if they expect these lower returns to continue? Without a doubt. Foreigners may be attracted to:

- the highly liquid US financial markets—especially investors in countries with small and less developed financial markets.6

- the strong corporate governance and accounting standards in the US. (Granted, recent problems with SIV’s and other structured products shows that these standards have room for improvement, but they are still perceived to be better than in many other countries.)

- the US as part of a standard portfolio diversification strategy, especially if returns in the investor’s country are less correlated with US returns.

- US investments due to close linkages to the US through trade, “familiarity” (such as sharing a common language or colonial history) and low information costs.

- the US due to the benefits of holding assets in the global reserve currency.

While all of these reasons could hypothetically motivate foreigners to hold US assets, which are actually important in practice?

The evidence

A recent analysis, “Why do Foreigners Invest in the United States?”, tests which factors drove foreign investment in US stocks and bonds between 2000 and 2006.7 It finds that the most important factor was the perceived advantages from the developed, liquid and efficient US financial markets. Even after controlling for a series of factors (including income levels), countries with less developed financial markets invested significantly more in the US relative to other countries and what optimal portfolio theory would suggest.

Although the benefit from the more developed and liquid financial markets in the US is not the only factor supporting US capital inflows, the empirical estimates suggest it can be important. For example, the estimates from the previous analysis suggest that if Italy improved its equity markets to a level comparable to France, then Italy would reduce its holdings of US equities by $3.7 billion. Taking a more extreme example, if China developed its bond markets to a level comparable to South Korea, it would reduce its holdings of US bonds by about $200 billion (compared to total holdings of $695 billion of US bonds at the end of 2006). Although this is only a fraction of total US Treasury, agency and corporate bonds outstanding, it is “real money”.

Implications for the Future of the Dollar

The role of differences in financial market development in supporting US capital inflows has several important implications. First, countries around the world will hopefully continue the progress they have made in developing and strengthening their own financial markets. This will gradually reduce this important incentive for countries to invest in the US. Any such adjustments and the corresponding effect on the dollar, however, would likely occur very slowly, since developing financial markets (especially in low-income countries) is a prolonged process.

Second, and potentially more worrisome, is the implication for recent events in the US. Recent market volatility, problems with US rating agencies and a lack of transparency in off-balance sheet structured products have raised concerns that US financial markets may not be the “gold standard” that they were previously believed. Recent discussion by the US Congress about rewriting mortgage agreements sets a worrisome precedent of government intervention in private contracts. Hostility to foreign investment has emerged in a few high-profile cases. This series of events has undoubtedly already reduced foreign willingness to hold US assets and accelerated the depreciation of the dollar over the past few months.

Conclusions

The US needs to improve its regulatory mechanisms in order to avoid a repeat of past excesses. But at the same time, the US government will hopefully not overreact and rush to pass a massive increase in poorly thought-out regulation. Any such response could seriously undermine the existing advantages of US markets and reduce foreigners’ willingness to invest the massive sums of money required by the US to support its current account deficit and capital outflows by US investors. The dollar could quickly return to its downward spiral. This need not occur if critical decisions on openness to foreign investment and financial market regulation are driven by cooler minds instead of election-year politicking. It is critically important that policymakers augment—instead of undermine—the long-term efficiency, resiliency and openness of US financial markets. If foreigners lose interest in investing in the US, additional reassuring words by Chairman Bernanke and Secretary Paulson, and even coordinated intervention in currency markets, could not support the dollar.

Footnotes

1 Assuming that the U.S. current account deficit in 2008 is $627 billion (IMF forecast) and gross U.S. capital outflows are between $1.2 trillion (equal to gross outflows in 2007) and $2.0 trillion (assuming growth in capital outflows from 2007 to 2008 equals the average annual growth rate from 2005 through 2007). Capital flow statistics from Bureau of Economic Analysis.

2 According to the Bureau of Economic Analysis, foreigners held $16 trillion in U.S. liabilities at year-end 2006 and data for 2007 is not yet available.

3 For evidence on return chasing, see Henning Bohn and Linda Tesar (1996), “U.S. Equity Investment in Foreign Markets: Portfolio Rebalancing or Return Chasing?” American Economic Review: Papers & Proceedings 86: 77-81. Also see Erik Sirri and Peter Tufano (1998), “Costly Search and Mutual Fund Flows,” Journal of Finance 53:1589-1622.

4 For more details on return calculations, see Kristin J. Forbes (2008), “Why do Foreigners Invest in the United States?” NBER Working Paper #13908.

5 For evidence that these return differentials between foreign investment in the United States and U.S. investment abroad did not exist in bonds, and probably in equities, over longer periods of time, see Stephanie Curcuru, Tomas Dvorak, and Francis Warnock (2008), “The Stability of Large External Imbalances: The Role of Returns Differentials,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, forthcoming.

6 For excellent theoretical models of this relationship, see the following three papers. (a) Ricardo Caballero, Emmanuel Farhi and Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas (2008), “An Equilibrium Model of ‘Global Imbalances’ and Low Interest Rates,” American Economic Review 98(1): 358-93. (b) Jiandong Ju and Shang-Jin Wei (2006), “A Solution to Two Paradoxes of International Capital Flows,” NBER Working Paper #12668. (c) Enrique Mendoza, Vincenzo Quadrini and José-Víctor Ríos-Rull (2006), “Financial Integration, Financial Deepness and Global Imbalances,” NBER Working Paper #12909.

7 Kristin J. Forbes (2008), “Why do Foreigners Invest in the United States?” NBER Working Paper #13908.