Sudden impoverishment as a trigger of civil conflict

Does poverty cause civil conflict? This column presents the latest evidence, which shows that droughts in Sub-Saharan Africa that reduce income raise the likelihood of violence.

Search the site

Does poverty cause civil conflict? This column presents the latest evidence, which shows that droughts in Sub-Saharan Africa that reduce income raise the likelihood of violence.

Is civil conflict triggered by impoverishment? The studies of Collier and Hoeffler (1998, 2004) and Fearon and Laitin (2003) have shown that poverty and civil conflict go together. But does the positive correlation between civil conflict and impoverishment prove that conflict is caused by impoverishment? There are good reasons to be cautious as both civil conflict and economic hardship are often symptoms of broad ranging social and political problems (Banerjee, Deaton et al., 2006). There is also the chicken-egg question: does impoverishment increase the likelihood of conflict, or is it that a higher likelihood of conflict leads to impoverishment (see the Vox columns by Fisman and Miguel and Djankov and Reynal)?

To see whether impoverishment causes the onset of civil conflict, I take a detailed look at data on rainfall levels in years before the outbreak of civil conflicts in Sub-Saharan African countries between 1980 and 2006. It is well known that living standards in these countries tend to be below trend in drought years and above trend when rainfall levels are above average. If civil conflict is triggered by sudden impoverishment, civil conflict onset in Sub-Saharan Africa should therefore have been more likely following drought years.

Droughts and civil conflict outbreakThere were 48 civil conflicts in Sub-Saharan Africa that started during the 1980-2006 period (UCDP/PRIO civil conflict data; see the International Peace Research Institute, 2007). Were these conflicts more likely to start following droughts? To see this, I examine Sub-Saharan African countries one by one and ask: How many civil conflicts started following the 10 years with lowest rainfall? And how many started following the 10 years with highest rainfall? We would expect the same number of conflict outbreaks if conflict were as likely following low rainfall as it was following high rainfall.

But the data show almost twice as many conflict onsets during low-rainfall-years – 23 conflicts started following low-rainfall years and 12 following high-rainfall years. Put differently, 2/3 of civil conflicts started in the 10 years with lowest rainfall and 1/3 in the 10 years with highest rainfall. Of course, there is a chance we might observe more civil conflicts following low-rainfall years even if conflict were as likely during low- and high-rainfall years. But that is not very likely. If civil conflict was equally likely following low- and high-rainfall years, the probability that 2/3 or more of 35 conflicts start following low-rainfall years is less than 5%. The hypothesis that civil conflict is more likely following low-rainfall years can therefore not be rejected using standard criteria of statistical confidence.

The picture becomes even clearer when I consider the 8 years with lowest rainfall and the 8 years with highest rainfall in each country. In this case, 20 of 29 conflicts that started during these years – almost 70% – did so following low-rainfall years. Chance deviation from the 50%-50% outcome is again unlikely to be driving this result. If civil conflict was equally likely following high and low rainfall, the probability that 20 or more of 29 civil conflicts take place following low-rainfall years is only 3%.

To confirm this pattern, I turn to regression analysis. I start by defining an indicator variable that is 1 in the year a civil conflict starts and 0 otherwise. The conflict onset indicator is then regressed on lagged rainfall levels (in logs). My analysis also allows for civil conflict being more likely to break out in some countries than others (see Ciccone, 2008, for details). Empirical results indicate that rainfall levels 10% below the country average raise the likelihood of civil conflict onset almost 1 percentage point above the country average, and that this effect is statistically significant at the 92% confidence level. The effect becomes stronger quantitatively and statistically when I account for common shocks to the probability of civil conflict onset (e.g. that conflict onset became more likely after the end of the Cold War). In this case, rainfall levels 10% below average raise the likelihood of conflict onset 1.25 percentage points above average, and the effect is statistically significant at the 96% confidence level. The results strengthen further when I allow the probability of conflict onset to follow different trends in different countries. When I consider only civil wars – defined as civil conflicts with more than 1000 annual battle deaths – I do not find a link with droughts however.

Rainfall growth and civil conflict outbreakThose who follow the academic literature on civil conflict and economic shocks will recognise that my analysis is closely related to the work of Miguel, Satyanath, and Sergenti (2004). Miguel, Satyanath, and Sergenti relate civil conflict onset to rainfall growth, and find that civil conflict is more likely to break out following years of negative rainfall growth (falling rainfall levels). I relate the probability of civil conflict onset to whether rainfall levels are low or high relative to the country average (to examine the effects of droughts). The two approaches have different implications because rainfall levels have a strong tendency to revert to the mean.

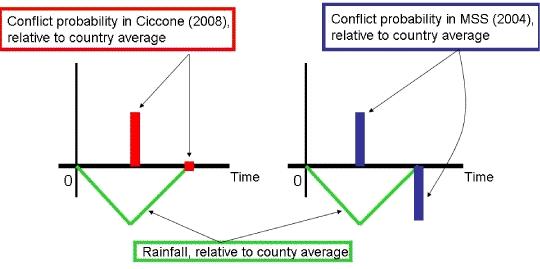

For example, the approach of Miguel, Satyanath, and Sergenti implies that conflict risk during the course of a “typical” drought first rises above the country average and then falls below average. This is because rainfall levels fall going into a drought year but tend to rise after the drought due to mean reversion. Figure 1 illustrates conflict risk during the course of a typical drought in the approach of Miguel, Satyanath, and Sergenti (MSS) and my approach. It can be seen that my approach implies a higher risk of civil conflict following years where, due to a negative rainfall “shock”, rainfall growth is lower than expected. But, in contrast to MSS’s approach, civil conflict risk returns to the country average as rainfall levels revert to the mean. Another, related, difference is that my approach implies that the risk of future civil conflict is greatest following droughts. MSS’s approach implies that the risk of future civil conflict is about average in this case (above average in the following year and below average in the year thereafter).

Figure 1. Civil conflict risk during the course of a "typical" drought

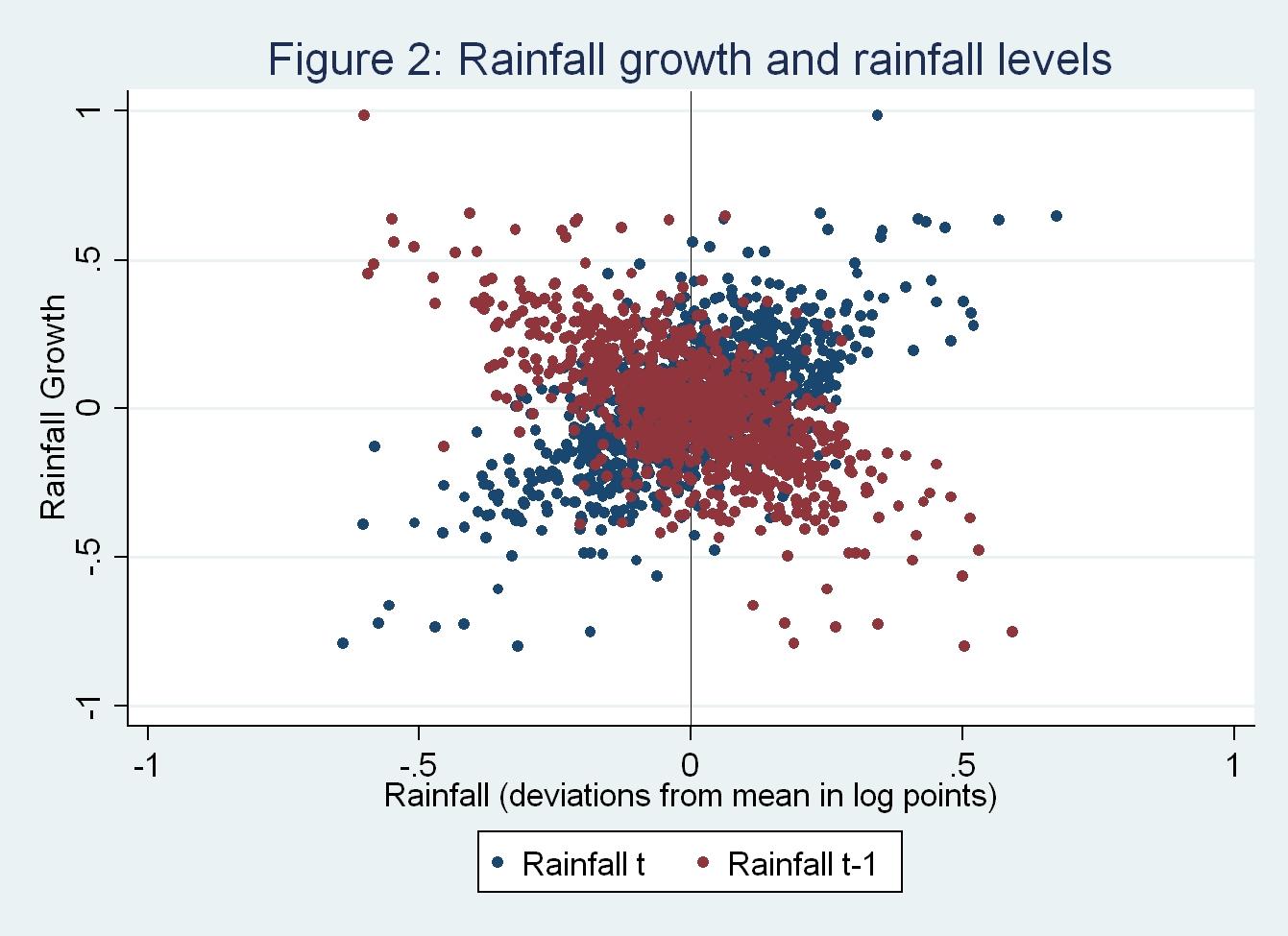

Empirically, mean reversion of rainfall levels is so strong that low rainfall growth is about as likely following high rainfall years as preceding low rainfall years. Figure 2 shows this. The red cloud of points illustrates the correlation between rainfall growth and preceding rainfall levels (rainfall t-1) measured in terms of percentage deviations from country averages. Due to mean reversion, the correlation is negative: the higher preceding rainfall levels, the lower rainfall growth. The figure also illustrates the positive correlation between rainfall growth and subsequent rainfall levels (rainfall t). The two clouds of points are almost perfectly symmetric around the vertical axis centred at zero. Hence, when we observe an X% fall in rainfall from one year to the next, rainfall levels might have been Y% above average in the first year or Y% below average in the second year. Miguel, Satyanath, and Sergenti’s finding linking civil conflict onset to low rainfall growth is therefore consistent with civil conflict being triggered by below-average or above-average rainfall.

As a result, their approach does not address the question whether civil conflict is triggered by negative rainfall shocks. In Ciccone (2008), I show that if conflict is more likely to break out following years of low rainfall, the effect of rainfall growth on conflict onset could be absent, significantly positive, or significantly negative.

ConclusionIf civil conflict onset is partly driven by sudden impoverishment, conflict outbreak in Sub-Saharan Africa should be more likely following below-average rainfall years. I find this to be the case. This result, combined with the effect of rainfall on income, allows me to estimate the effect of sudden impoverishment on the probability of civil conflict onset. My estimates indicate that a negative 5% income shock raises the likelihood of civil conflict by 15 percentage points.

ReferencesBanerjee, A., Deaton, A. et al (2006). An Evaluation of World Bank Research, 1998 – 2005.

Ciccone, A. (2008). “Transitory Economic Shocks and Civil Conflict”. CEPR Discussion Paper 7081. For the data and estimation programs see www.antoniociccone.eu

Collier, P. and A. Hoeffler (1998). “On Economic Causes of Civil War.” Oxford Economic Papers 50 (3): 563-573.

Collier, P. and A. Hoeffler (2004). “Greed and Grievance in Civil War.” Oxford Economic Papers 56 (4): 563-596.

Fearon, J. and D. Laitin (2003). “Ethnicity, Insurgency and Civil War.” American Political Science Review 97 (1): 75-90.

International Peace Research Institute (2007). UCDP/PRIO Armed Conflicts Dataset. http://www.prio.no/CSCW/Datasets/Armed-Conflict/

Miguel, E., S. Satyanath, and E. Sergenti (2004). “Economic Shocks and Civil Conflict: An Instrumental Variables Approach.” Journal of Political Economy 112 (41): 725-753.

210 Reads