Large cross-border banking groups dominate the global banking landscape (Claessens and van Horen 2014). Differences in regulatory systems and imperfect supervisory cooperation across countries provide opportunities for these banking groups to take on higher risk than if they were subject to only one very stringent regulator. In recent years, policymakers have stepped up their efforts to improve supervisory coordination across countries (most prominently, the Banking Union in Europe). However, these agreements are predominantly between two or more countries, but not necessarily all the countries in which a group cooperates. This fact opens up the possibility of regulatory arbitrage.

In a recent paper, we find evidence for risk-shifting by global banking groups in response to cross-border supervisory cooperation (Beck et al. 2022b). However, we also find that specific regulatory policies can mitigate the impact of such risk shifting.

Theory and literature

Empirical evidence has shown that banks adjust their behaviour to changes in regulatory frameworks (Barth et al. 2004, Laeven and Levine 2009) and shift risks to business lines or countries with less stringent regulation (Ongena et al. 2013, Buch et al. 2016). Banks might also change their behaviour following changes in supervisory architecture (Gopalan et al. 2021, Eber and Minoiu 2016).

Theory suggests that the international supervision architecture, including cooperation between national supervisors, can also influence banks’ behaviour. Calzolari and Loranth (2009) show that the allocation of supervisory responsibilities impacts the incentives of a bank to expand outside its home country, as well as the organisational form of this expansion. Calzolari et al. (2016, 2019) find that cooperation between national supervisors increases the supervisory monitoring of banks, which in turn provides incentives for banks to close their foreign operations or change the organisational structure from subsidiaries to branches.

We build on these theoretical insights and test the effect of closer cross-border cooperation on banks’ behaviour, including their risk-taking, using both subsidiary-level and loan-level data.

Data

We use hand-collected data on supervisory cooperation agreements from Beck et al. (2022a). The dataset contains information on cooperation at the country-pair level (but such cooperation may originate from a multilateral agreement) between 1995 to 2013. On average, a banking group has ten subsidiaries spanning on average nine countries.

Our analysis is based on 663 subsidiaries belonging to 113 banking groups in 90 host countries and 40 home countries. The most common case is a subsidiary in a developing country with a parent from a developed country (54%, using the country classification of the IMF), followed by both subsidiary and parent being from a developing country (31% of cases), and the case of both subsidiary and parent being from a developing country (14% of cases).

Methodology

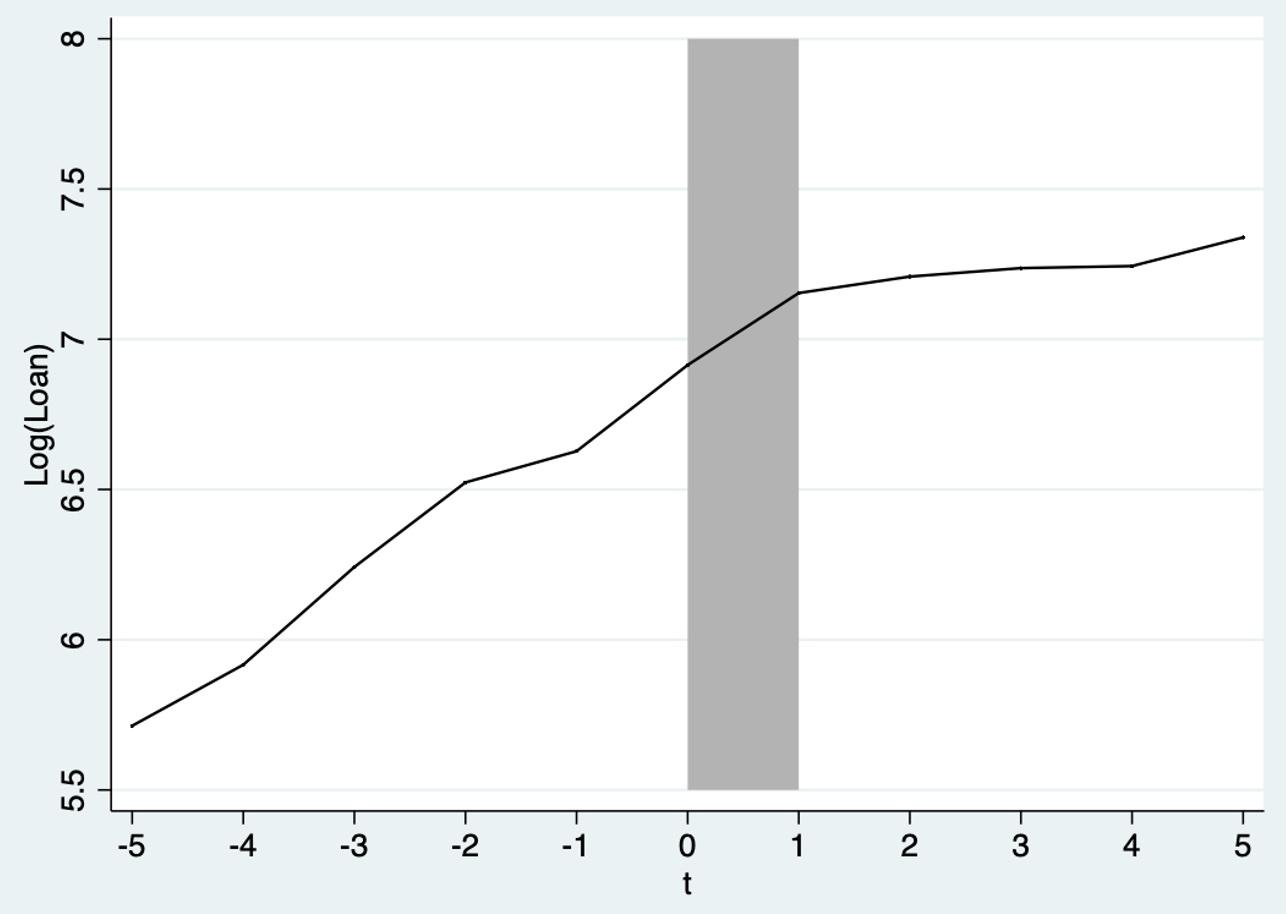

Our main analysis takes place at the subsidiary-level. Figure 1 depicts lending in a subsidiary around the time when cooperation with the home country is (first) initiated. Cooperation starts in the period between time = 0 and time = 1, indicated by the shaded area in the graph. We can see that following cooperation, there is a slowing of loan growth in the affected subsidiary. This is consistent with cooperation limiting regulatory arbitrage and making it more difficult to hide risks (from the home supervisor), resulting in less risk being allocated to the foreign subsidiary.

Figure 1 Lending and subsidiary-parent supervisory cooperation

However, we cannot interpret this evidence as causal, as cooperation agreements might be accorded in light of expected bank behaviour. In our main analysis, we therefore focus primarily on third country effect, i.e. how changes in supervisory cooperation between home and host countries of a banking group affect third-party host countries.

Specifically, we relate different outcome variables on the subsidiary level to a variable that measures the extent to which the subsidiary’s banking group is covered by cooperation between parent and other host country supervisor excluding subsidiaries located in the subsidiary’s country, weighted by the share of each subsidiary’s assets in total foreign assets of the banking group. We saturate our regression model with other subsidiary characteristics and a number of fixed effects. In our most stringent specification, identification will come from the fact that two subsidiaries located in the same country with parents that are also headquartered in the same country are differentially exposed to third countries signing cooperation agreements with the home country, as the geographic footprint of banking groups differs.

To illustrate our approach, Figure 2 shows the example of the Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS).1 RBS has subsidiaries in nine different countries, eight of them developing countries. In 2008, only one subsidiary was covered by a cooperation agreement (the subsidiary in Mexico). However, in 2009, the UK signed cooperation agreements with three countries (Ireland, Poland, and Romania). Thus, the fraction of subsidiaries covered by cooperation agreements increased significantly (four out of nine subsidiaries are now covered) and the question arises whether caused RBS to shift risk into the remaining five subsidiaries without cooperation agreements.

Figure 2 Group structure and supervisory cooperation for Royal Bank of Scotland

Our main findings

- Lending in a subsidiary increases when group-level cooperation between parent bank supervisor and other host country supervisors increases. The effect is an economically large as a one standard deviation change in group cooperation increases subsidiary lending by 29%. We interpret this as evidence for resource shifting following changes in supervisory cooperation.

- This increase in lending is funded by debt rather than equity, and thus the subsidiary’s liability side becomes riskier. We do not find any evidence for potentially offsetting effects, such as from safer or more profitable lending. Together with the previous results, this evidence suggests risk shifting into subsidiaries not yet subject to supervisory cooperation.

- Risk shifting is larger into better-capitalised subsidiaries, while there is no risk shifting if there is a cooperation agreement between the specific subsidiary host supervisor and the parent bank supervisor. We also find that higher cooperation of the host country supervisor with other host countries’ supervisors results in lower lending when supervisory cooperation between home and third-party host country supervisors increases.

- Risk-shifting into the subsidiary is stronger when the subsidiary’s host country has weak supervision relative to other countries where the group has foreign operations and when (relative) market discipline in the host country is lower, as indicated by the existence and generosity of a deposit insurance system.

- Using syndicated loan data, we find that the probability of booking a specific syndicated loan at a specific subsidiary increases as cooperation between home country and other host country supervisors increases, providing additional evidence for risk shifting to parts of the banking group that are not subject to supervisory cooperation. The probability of shifting syndicated loans to subsidiaries not subject to changes in supervisory cooperation is higher for riskier borrowers.

Conclusions

Our results thus indicate that supervisory cooperation between parent and host country supervisor can lead to risk-shifting within a banking group, consistent with regulatory arbitrage. Such risk-shifting may make cooperation less effective and possibly render it ineffective overall. These findings might also explain why in previous work (Beck et al. 2019, 2022a) we find that, whereas supervisory cooperation makes smaller cross-border banking groups safer, this is not the case for the larger ones. Those that operate across many countries and therefore have more opportunities for regulatory arbitrage.

Notably, our results suggest that cooperation creates potential conflicts across countries. Cooperation between two countries may benefit those countries by shifting risk to third countries. Cooperation thus potentially entails negative externalities. This evidence indicates that actual cooperation decisions made (relatively) independently by pairs of countries (or sets of countries) can lead to inefficient outcomes. This fact points to a rationale for ‘cooperating on cooperation’.

References

Barth, J R, G Caprio and R Levine (2004), “Bank regulation and supervision: what works best?”, Journal of Financial Intermediation 13: 205-24.

Beck, T, C Silva-Buston and W Wagner (2019), “The effectiveness of cross-border cooperation in banking supervision”, VoxEU.org, 4 September.

Beck, T, C Silva-Buston and W Wagner (2022a), “The Economics of Supranational Bank Supervision”, Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, forthcoming.

Beck, T, C Silva-Buston and W Wagner (2022b), “Supranational cooperation and regulatory arbitrage”, CEPR Discussion Paper 16978.

Buch, C, M Bussiere, and L Goldberg (2016), “Prudential policies crossing borders: Evidence from the International Banking Research Network”, VoxEU.org, 9 December.

Calzolari, G, J Colliard and G Loránth (2016), “The Single Supervisory Mechanism and multinational banks”, VoxEU.org, 30 July.

Calzolari, G, J Colliard and G Loránth (2019), “Multinational Banks and Supranational Supervision”, Review of Financial Studies 32: 2997-3035.

Calzolari, G and G Loránth (2011), “Regulation of Multinational Banks: A Theoretical Inquiry”, Journal of Financial Intermediation 20: 178–98.

Claessens, S and N van Horen (2014), “Foreign Bank: Trends and Impact”, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 46: 295-326.

Eber, M and C Minoiu (2016), “How do banks adjust to stricter supervision?”, working paper.

Gopalan, Y, A Kalda and A Manela (2021), “Hub-and-spoke regulation and bank leverage”, Review of Finance 25: 1499-1545.

Laeven, L and R Levine (2009), “Bank governance, regulation and risk taking”, Journal of Financial Economics 93: 259-75.

Ongena, S, A Popov and G Udell (2013), “When the cat is away the mice will play: Does regulation at home affect bank risk-taking abroad?”, Journal of Financial Economics 108: 727–750.

Endnotes

1 This is a simplified organisational structure, focusing only on the subsidiaries within our sample and relevant for our analysis. Dark gray boxes indicate that cooperation exists between the two countries, light gray boxes indicate that no cooperation exists. The percentages in the boxes show the asset-weighted cooperation indicator between the UK and the Royal Bank of Scotland's subsidiaries' host countries, excluding the subsidiary's country.