Two things are certain in life: Death and taxes. As evidenced by Facebook groups like ‘I Hate Paying Taxes!’, it’s not clear which of the two people dislike more. Indeed, people can prefer to pay more for a product and avoid tax than get the product for cheap but know that the government is taking a cut (Sussman and Olivola 2011). This ‘tax aversion’ is no small matter. The US has an estimated annual ‘tax gap’ of almost $400 billion due to non-compliance (Internal Revenue Service 2012), while in the UK the gap stands at £42 billion (HMRC 2013).

In recent research, we tackled a tough problem: Could we make people hate taxes a little less, and in the process raise tax compliance? We found that there are two critical dynamics underpinning people’s tax aversion (Lamberton et al. 2014):

- First, taxpayers have little sense of where their money is actually going – unlike buying a sandwich when you know exactly what you get for your money.

- Second, taxpayers feel that they have no influence in the decision-making as to where their taxes will be spent. As a result, paying taxes can feel like dumping a lot of money into a black hole – no wonder it can be so frustrating.

Solutions

We propose two simple solutions to these two issues.

- The first is to better inform people, bridging the knowledge gap between paying taxes and the public goods that taxpayers receive in return.

- The second is to give taxpayers an opportunity to express their preferences on public spending – to give them increased ‘taxpayer agency.’

In a first experiment, we brought almost 200 people into our lab to complete some tasks in return for cash, with one catch – we informed them that they would need to pay a 30% tax on their wages and leave it behind in envelopes. We allowed some people to tell us where they thought we should spend their taxes – for example, on improvements to our laboratory.

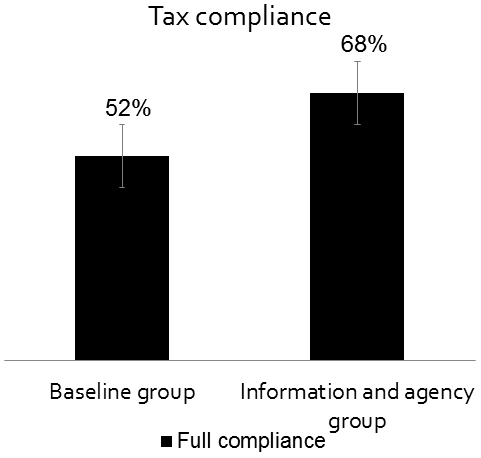

We found that compared to people not given this taxpayer agency, a lot more money ended up in the envelopes from those given a voice. In fact, full tax compliance rose from 52% to 68% simply by allowing people to express their preferences. Even better, when we asked them how they felt about the process, people given agency weren’t any less happy – even though they’d given us more of their money. To the contrary, their attitudes towards taxation actually improved.

Figure 1. Experiment 1: lab tax study

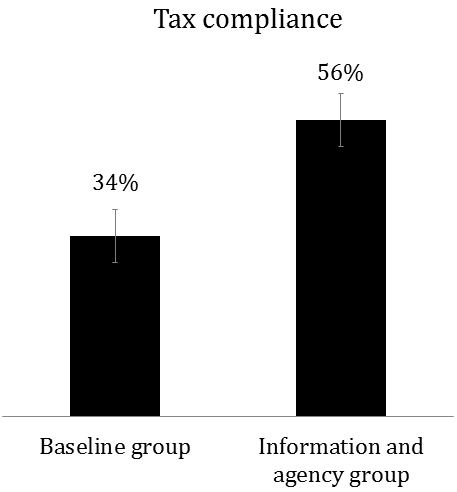

In a second experiment, we explored whether taxpayer agency might lead people to be less likely to take a questionable tax loophole. We showed some people a pie chart of the US national budget – broken down into actual spending categories – and let them tell us what they thought the budget priorities should be by playing with the allocations in the chart. We made it clear that while their preferences would be taken into account, the policymakers would continue to make the final decisions.

Did people cheat more, or less? As before, we witnessed a big shift – those who played around with the budget were much less inclined – a full 20% less likely – to take the questionable tax loophole.

Figure 2. Experiment 2: loophole study

Interestingly, once we compiled people’s preferences for the US budget, there were no dramatic changes from the current spending distribution. Defence spending came down a bit, and education and job training went up. Generally, however, people’s aggregate preferences did not deviate significantly from the current priorities.

Our research shows that these effects occur when taxpayer agency is non-binding – people are given a voice in the process but not the actual decision – distinguishing our results from the old hypothecation debate. Participants in our experiments knew that their preferences would be non-binding – what mattered was that they felt that they were able to contribute to tax policy.

In addition, our results revealed that adding taxpayer agency is substantially stronger than is simply providing information about how taxes are allocated. This is practically important, as both the US and the UK have placed stock in the power of information in increasing taxpayer satisfaction and, presumably, compliance.

Concluding remarks

Our research suggests that the annual tax filing process offers an unexploited opportunity for governments to engage with taxpayers – simply by making the tax form more interactive. Doing so can increase tax compliance, while empowering citizens and improving their attitudes towards taxation.

Furthermore, the costs are low. Most of us have to go through the tax process every year, whether on paper or online, and our intervention involves adding just a few questions to existing forms. Our recommendation? Give taxpayers a voice!

References

HMRC (2013) Measuring tax gaps 2013 edition.

Lamberton C, J-E De Neve and M I Norton (2014) “Eliciting Taxpayer Preferences Increases Tax Compliance.” HBS Working Paper 14-106.

Internal Revenue Service (2012) The tax gap.

Sussman, A B and C Y Olivola (2011), “Axe the tax: Taxes are disliked more thanequivalent costs.” Journal of Marketing Research 48 (special issue), S91-S101.