Europe has many flavours of social contracts depending on the degree to which individual countries protect their citizens from socioeconomic risks, how much they redistribute revenue generated, and which citizens are entitled to benefit from those contracts. Within this diversity, however, Europe’s social contracts have a common backbone – they are based on a long-established inclusive growth model characterised by a more egalitarian view of revenue generation and distribution (Esping-Andersen 1999).

European cracks

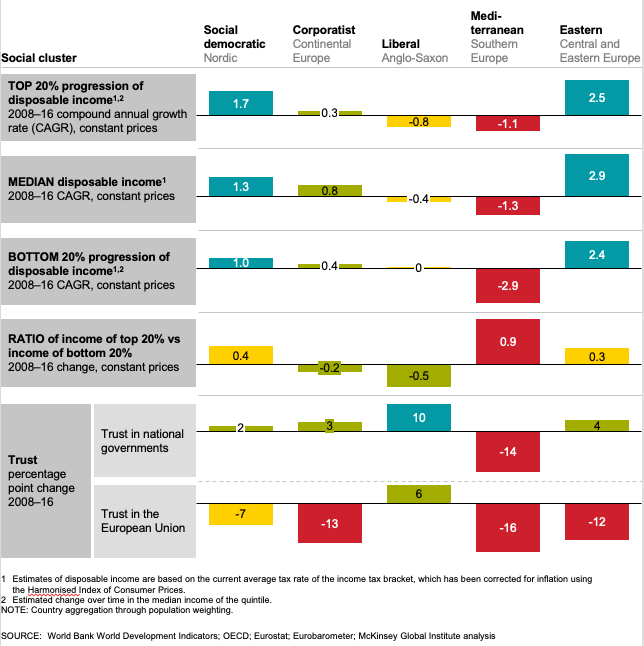

Europe’s social progress had been remarkable (Fehder et al. 2017, Benabou 2000). However, in recent years, the economic crisis has put significant strain on this model, especially for the Mediterranean cluster. Countries in that cluster have been the most hit by the crisis and in response have cut social spending, among others, leading to increased inequality with many citizens still fearing that worse is to come. More broadly speaking, the median income growth in Europe has been trailing beyond its long-term trend, and many citizens are expressing those fears by voting for non-mainstream political parties and voicing their reluctance to accept more migration. Trust in institutions (both own-country and EU, for member states’ citizens) has also been declining in one-third of European countries (Algan et al. 2017, Foster and Frieden 2017), see Figure 1.

Figure 1 Social clusters' performance has diverged in Europe since the crisis, with the Mediterranean cluster appearing worst off

Evidently, social contracts in the EU have been tested in every recent decade – by the oil shock in the 1970s, the growth of world trade and rising competition from Asian economies in the 1980s, and the information and communications technology bubble at the turn of the 21st century. During these periods, inequality rose, but then, as growth returned, settled back again.

A new ball game?

But this time may be different. New McKinsey Global Institute research suggests that the upward pressure on inequality could – this time structurally – intensify as the result of the interaction of six global trends that are coming of age at the same time. The six trends are ageing demographics; digital technology, automation, and artificial intelligence (AI); increased global competition and migration; climate change and pollution; and shifting geopolitics.

The ultimate impact of these megatrends on inclusive growth will depend on how actively European policymakers respond to them, either to seize positive opportunities or to mitigate potential negative effects.

Unlikely, but theoretically possible, is a ‘denial’ scenario in which the EU and European countries do not respond to the megatrends (and roll back current policies such as increases in the retirement age). The result would be prolonged secular stagnation (Gordon 2015), rising inequality, and growth in welfare costs that outstrip gross income growth. Our simulation suggests that the strength of the headwinds induced by the megatrends could be sufficiently large to reduce baseline income growth from an average of 1.6% per year to 0.3% (an 85% drop), not accounting for the likely depressive effect of rising inequality on income growth.

In contrast, if Europe scales up current policies on, for instance, ageing, actively enables the diffusion of digital and AI technologies, and invests in the circular economy (Ellen MacArthur Foundation and McKinsey Center for Business and the Environment 2015) – a ‘deliver’ scenario – it could achieve more solid per capita income growth of 1.9% a year, producing an additional €9,000 of per capita gross income that could fund additional public social spending to help citizens, whatever the disruptions that lie ahead.

However, even if Europe delivers necessary policies, rising inequality appears to be inevitable because of concomitant forces at work. For instance, digital technology and AI will put pressure on the wages of those doing routine jobs and pay premiums to the higher-skilled, while the deployment of the circular economy could potentially hit some sectors (including manufacturing) more than others.

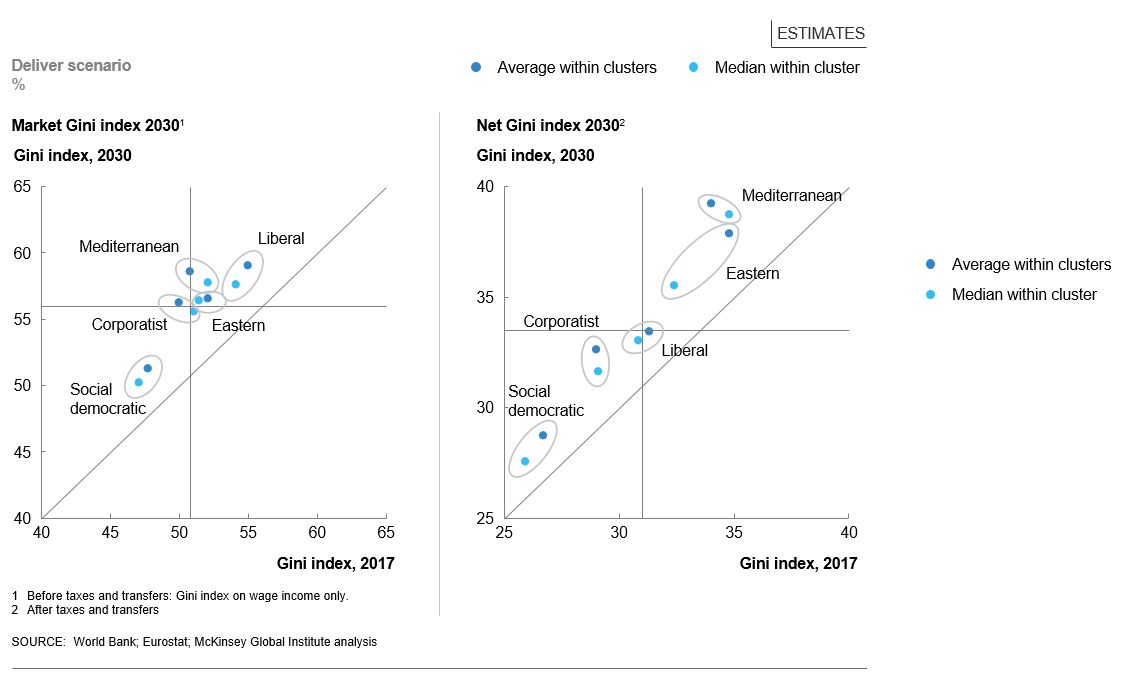

Alongside rising inequality among citizens within EU member states, more social divergence may develop among European countries. Europe’s ‘social democratic’ cluster of countries, which includes Nordic economies, has fared relatively well. These economies have experienced the highest GDP growth in the EU, leading to real positive growth in per capita income and a slight increase in inequality due to superior income growth in the top decile; there has been improved social progress and rising institutional trust (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Social divergence may spread within the EU28 even in a ‘deliver’ scenario

In stark contrast (and as highlighted in Figure 1), the ‘Mediterranean’ cluster of Southern Europe has still not fully digested the impact of the 2007/8 crisis. All income deciles and quintiles have lost between 1% and 3% a year of disposable income per capita with the lowest-income households experiencing the largest losses. Poverty and relative income inequality have increased. Among the most affected economies, median disposable incomes declined by as much as 5% a year in Greece over this period, and by about 1% per year in Italy and Spain.

Even in McKinsey Global Institute’s ‘deliver’ scenario, Southern Europe will continue to be challenged by its demographics, and, if it does not catch up with the rest of Europe on digital and AI capabilities, have lower potential to benefit from technology. Our estimate suggests that the cluster of Mediterranean countries may generate less than 1.5% of per capita income growth, compared with more than 2% in the other European clusters. Moreover, Southern Europe could experience double the increase in inequality as the north (see Figure 2).

With such challenges ahead, it may be tempting to resist change or alternatively to give up on the essence of the social contracts in Europe. This, however, may be a strategic mistake and backfire. Inequality may, in fact, boost entrepreneurship (Grigoli et al. 2016, Aghion 2003).

Furthermore, in the ‘deliver’ scenario, a large part of inequality is due to transformational change in the way we work (Acemoglu and Restrepo 2018), in the way we rethink pollution and climate externalities, and in the way we must adapt the pay-as-you-go model of pensions, for instance. These challenges need to be met no matter what, and the best – and vital – form of action is investing in skills, developing new models of workforce participation, and innovating. Only by doing so can Europe achieve inclusive growth in the medium term (Atkinson 2015).

Keeping the essence of its current inclusive growth model does not preclude Europe adapting its current social contracts in order to enable a fast and more effective transition. During a previous societal revolution, countries financed a new model of education, mandating citizens to go to high school, for instance, and launched the first model of union-firm industrial relations. In the new green and digital revolution, Europe will need to embed lifelong learning in the workplace, experiment more with the gig economy, and enforce new behavioural models with respect to limiting pollution and overuse of natural resources.

Some of the elements that need to be put in place may require strong political mandates, which could be very difficult in an era of low trust in politicians and institutions. But lack of action could leave the European inclusive growth model even more vulnerable. Challenging times – politically and economically – lie ahead. However, history has taught us that nations emerge from uncertain societal transitions by taking rapid action, engaging in fresh thinking, experimenting with new models of social contracts, and using social protection as an insurance against failure.

References

Acemoglu, D, and P Restrepo (2017), “Low-skill and high-skill automation”, NBER working paper 24119.

Aghion, P (2003), “Schumpeterian growth theory and the dynamics of income inequality”, Econometrica, Walras-Bowley Lecture.

Algan, Y, et al. (2017), “The European trust crisis and the rise of populism”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, BPEA Conference Drafts, September 7–8.

Atkinson, AB (2015), Inequality: What can be done?, Harvard University Press.

Benabou, R (2000), “Unequal societies: Income distribution and the social contract”, American Economic Review 90(1).

Ellen MacArthur Foundation and McKinsey Center for Business and the Environment (2015), “Growth within: A circular economy vision for a competitive Europe”.

Esping-Andersen, G (1999), Social foundations of postindustrial economies, Oxford University Press.

Fehder, D, M Porter and S Stern (2018), “The empirics of social progress: The interplay between subjective well-being and societal performance”, American Economics Association Papers and Proceedings 108.

Foster, C, and J Frieden (2017), “Crisis of trust: Socioeconomic determinants of Europeans’ confidence in government”, European Union Politics 18(4).

Gordon, RJ (2015), “Secular stagnation: A supply-side view”, American Economic Review 105(5).

Grigoli, F, E Paredes and G Di Bella (2016), “Inequality and growth: A heterogeneous approach”, IMF working paper 16/244.

McKinsey Global Institute (2018), “Testing the resilience of Europe’s inclusive growth model”, discussion paper.