The literature on innovation and international trade has, until recently, focused almost exclusively on the manufacturing sector. This is not surprising because the bulk of international trade has been in manufactured products and innovation has traditionally been associated with new or improved physical products. The services sector was ignored because it was seen as largely untouched by both trade and innovation. But today, many developing economies, from Malaysia to Mexico, see services exports and innovation as a potential source of dynamism for their economies and as a way of breaking out of the so-called ‘middle-income trap’. Is this faith justified?

While a number of studies from the innovation and marketing literature (for example, Erramilli and Rao 1993) have studied the internationalisation and innovation of firms in the services sector, their focus and methodologies are relatively distant from the current theoretical and empirical economic literature. The few firm-level analyses of services companies have so far focused exclusively on developed economies (Love and Mansury 2007, Pires et al. 2008, Eickelpasch and Vogel 2009 and Jensen and Kletzer 2005), even though the services sector is already the largest in many developing economies and a key determinant of overall productivity. For instance, recent studies suggest that sluggish productivity growth in the services sector of Latin American countries is a key reason for their limited productivity catch-up with the US (IADB 2010).

In a recent study, we compare the manufacturing and ‘tradable’ services sector from a joint trade and innovation perspective, relying on detailed firm-level data (Iacovone, Mattoo and Zahler 2013). We focus on Chile, an upper-middle economy that has undertaken a special effort to promote the internationalisation of its service sector. We analyse a firm-level innovation survey – carried out in 2007 and covering the period 2005-06 – that includes both manufacturing and services firms.

Our results should be seen in the broader context of Chile’s services trade. In recent years, commercial-services exports accounted for as much as one-third of Chile’s non-copper exports. Within commercial services, transport and logistics services made up more than half of the total – thanks to the strength of Chile’s airline and maritime services. The exports of other business services, which include outsourced business process, were only about one-sixth of the total, reflecting their relatively slow development in Chile. Chile is also beginning to export services related to mining – drawing upon its rich experience in extracting copper. Exports of retail services have also grown but mostly take place through the establishment of a commercial presence abroad and are not captured in conventional trade statistics.

But what really is innovation for a services firm? To better understand the elusive notion of services innovation, consider some examples of innovation from three Chilean services companies (borrowed from Bravo et al. 2013):

- Enaex, a firm that provides rock blasting services to mining companies, has become a global pioneer in optimising choices of location, explosive mixing and dosage, while maintaining high safety standards.

It created Milodon, the world's largest truck for mixing and loading of explosives, which reduces the number of people, trucks and equipment moving through the mine in each loading cycle and minimises risks for operators. In parallel, it developed Inteliblast software that processes input data, such as compression and fracture frequency, and determines the type of rock fragmentation strategy. This information is transmitted to the Milodon, which has a GPS device mounted on the arm allowing detection of the location of the perforation, the type and volume of explosives to charge, and thus develop customised designs of the blasting processes based on field data.

- The retail company Cencosud has created a new client interface to enhance customers shopping experience;

For example, in the electronics section, it has moved beyond the standard practice of relying entirely on in-store brand promoters – who bombarded consumers with information on their own specific brands and left them confused – and introduced an initial adviser who advises clients on the best product suited for their needs as well as an expert who is available to answer technical questions and to train costumers in-store.

- The port terminal in the region of Arica and Parinacota has developed innovations related to the improvement of the port’s layout, slot allocation for management of trucks at the port, automation of electronic records of the port loads entered, and designed a system to efficiently trace loads.

The first case shows technological innovation and is similar to innovation in manufacturing. The other two cases are examples of non-technological innovation. The retail case involves rethinking the way a company relates to customers, but affects customer experience, time spent by both salespeople and consumers, and overall productivity. Interestingly, it is precisely this type of innovation which has helped Cencosud become a big player in Latin American retail. The port example involves a reallocation of resources and redesigning the way services are provided, which can also have an impact on productivity, even though it does not incorporate new ‘hard’ technologies.

These examples allow us to better understand the three main sets of findings emerging from our study. The first two relate to services firms’ exporting and innovating behaviour; while the third relates to the links between trade and innovation.

Manufacturing and innovation

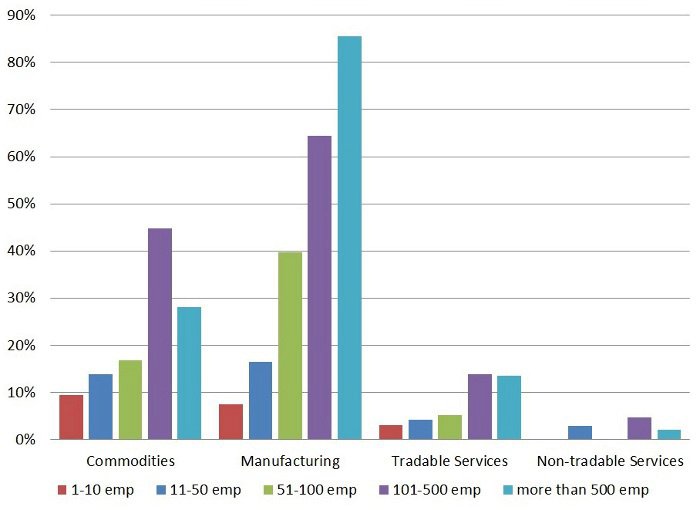

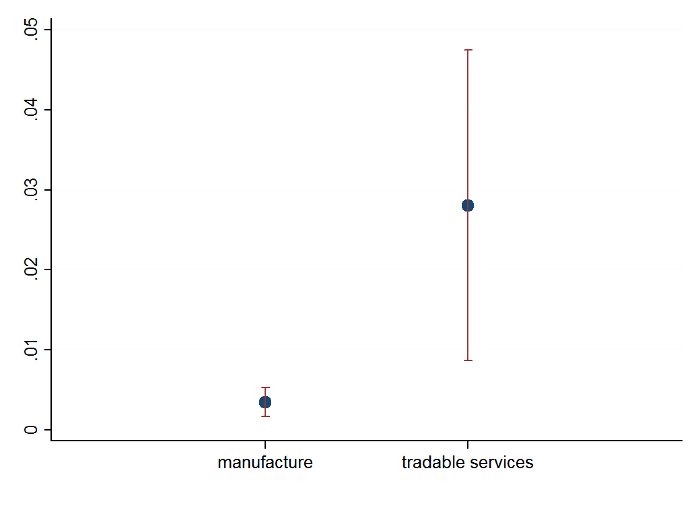

First, even if a much smaller proportion of services firms export when compared to manufacturing, those that do are not necessarily much larger than non-exporters as is the case in the manufacturing sector (Figure 1). We suggest that this pattern can be explained by the relatively greater reliance of services exporters on skills rather than scale. In fact, we find that while all exporters tend to be more skill-intensive than non-exporters, the ‘export skills premium’ is greater in services than in manufacturing (see Figure 2).

Figure 1. Export propensity and firm size: % of firms in relevant size category that export 2005-06 weighted sample

Figure 2. Exporter premium: skill intensity

Services and innovation

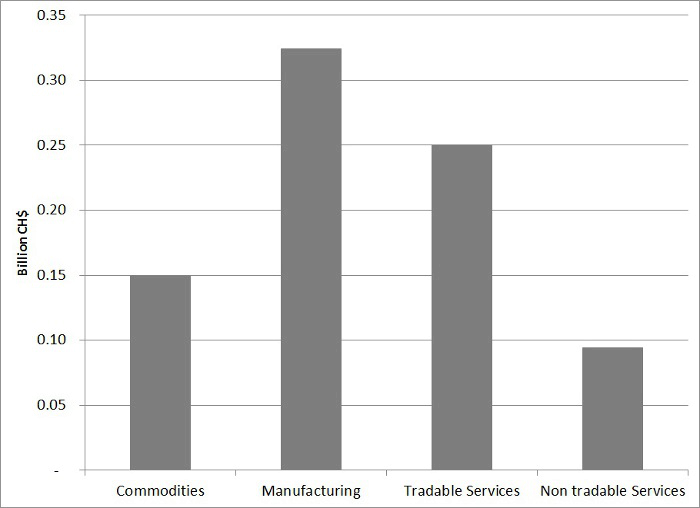

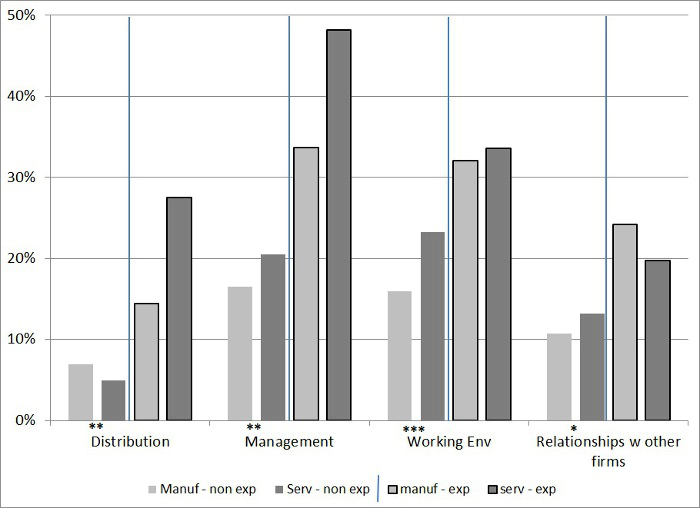

Second, services firms appear to be as innovative as manufacturing firms, in terms both of investments in innovative activities (see Figures 3 and 4) as well as in terms of their results or outputs, measured using both subjective and objective indicators. However, services firms tend to rely relatively more on non-technological forms of innovation than manufacturing firms (Figure 5). These refer to innovations in product design and organisational management in production, work environment or management structure of the firm (i.e. as in the examples of Cencosud and the Port of Arica), as opposed to ‘technological’ innovation, which refers to introduction of new products or processes in the market, and expenditure related to R&D, physical equipment acquisition and training related to them (i.e. the examples of Enaex).

Figure 3. Expenditure on innovation by sector, (Average 2005-2006, using weights)

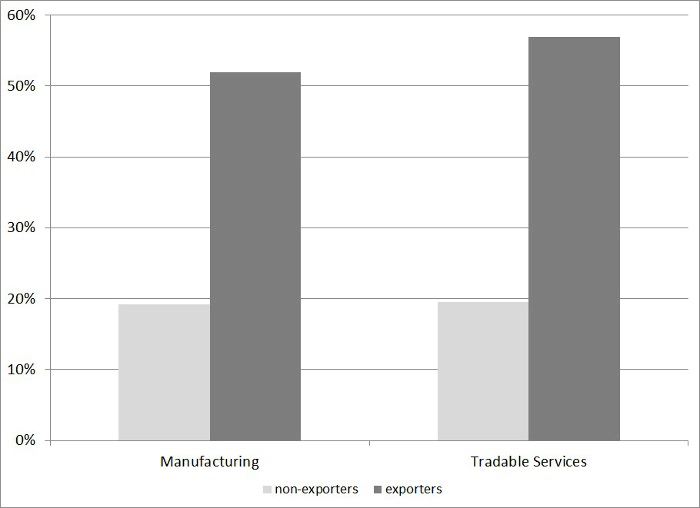

Figure 4. Propensity to spend on innovation of exporters and non-exporters

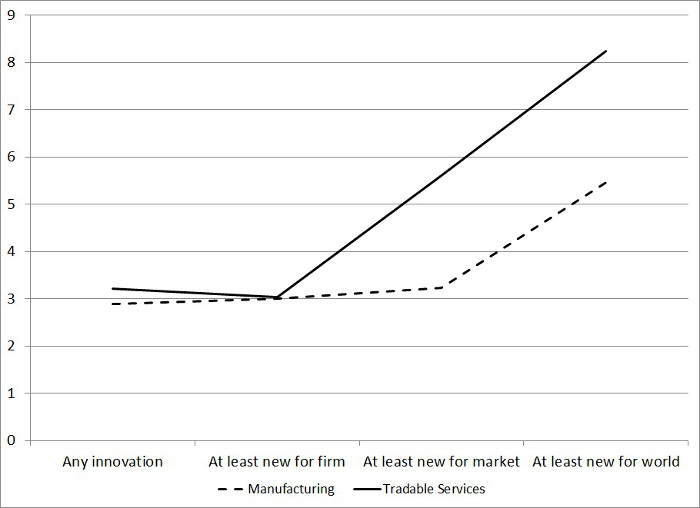

Third, we find that exporters both in manufacturing and services tend to invest more in innovation than non-exporters (Figure 4), and be significantly more innovative than non-exporters (Figure 5). Moreover, the gap in innovation between exporters and non-exporters increases for innovations that are closer to the global technological frontier (Figure 6).

Figure 5. Non-technological innovation propensity and export status

Notes: * Significantly different at 10% ** Significantly different at 5% *** Significantly different at 1%

Figure 6. Ratio of percentage of firms that innovate between exporters and non-exporters

Overall, these findings provide some support in favour of the optimistic view of services as a potential source of growth dynamism. They also suggest that we need to improve our understanding of how firms in the services sector innovate and increase productivity, and of whether tailored policies can promote trade and innovation in services.

References

Iacovone, Leonardo, Aaditya Mattoo and Andrés Zahler (2013), “Trade and Innovation in Services: Evidence from a Developing Economy”, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 6520, Washington, DC.

IADB (2010), “The age of Productivity: transforming economies from the bottom up”, Palgrave Macmillan, March.

Bravo, C and Muñoz, L & Zahler, A & Alvarez, R (2013), “Case Study Analysis for Chile Innovation in Services Project CINVE-IADB”, mimeo, May.

Eickelpasch, A and Vogel, A (2009), “Determinants of Export Behaviour of German Business Services Companies”, DIW Berlin Discussion Papers, 876.

Jensen, JB and Kletzer, LG (2005), “Tradable Services: Understanding the Scope and Impact of Services Outsourcing”, Working Paper Series WP 05-9, Institute for International Economics, Washington DC.

Love, J and Mansury, MA (2007), “External linkages, R&D and innovation performance in US business services”, Industry and Innovation 14(5), 477–496.

Pires, CP and Sarkar, S and Carvalho, L (2008), “Innovation in services-how different from manufacturing?”, The Service Industries Journal 28(10), 1339–1356.