With the recent souring of relations between China and the US, the notion of trade wars is no longer consigned to academic treatments of the disastrous interwar period (Bown and Zhang 2019). Indeed, trade wars have re-emerged as a topic of considerable interest to policymakers. And naturally, observers have been quick to draw parallels between recent changes in commercial policy and the experience of the world economy in the 1930s.

But what precisely were the causes and consequences of the trade wars in the 1930s? Were there perhaps deeper forces at work in reorienting global trade prior to the outbreak of WWII? And what lessons may that particular historical episode provide for the present day? In a new paper (Jacks and Novy 2019), we attempt to answer these questions. But at the same time, we emphasise the limits of historical parallels across two time periods with some common features that nevertheless emerge from very different environments.

Post-war recovery of global trade

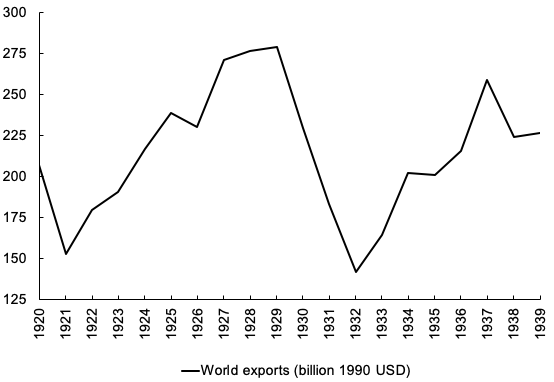

After suffering through the short-lived worldwide deflationary episode of 1920-1921, world exports grew by 82.5% in the eight years from 1921 to 1929 (see Figure 1). Additionally, the distribution of world exports as depicted in Figure 2 was quickly converging to its pre-war equilibrium. In 1929, European exports were 53.9% of the world total (as compared to their 57.7% share in 1913) Thus, the global economy seemed well on its way to a successful recovery from the trauma induced by WWI.

Figure 1 World exports, 1920-1939

Data source: Jacks and Tang (2018)

Figure 2 Shares of world exports, 1920-1939

Data source: Jacks and Tang (2018)

The twin shocks of 1929

However, all such expectations faded shortly after 1929 when two large shocks emerged in the world economy. The simultaneous decline in global economic activity and the drafting of the Smoot-Hawley tariff bill from the summer of 1929 (signed into law in June 1930) constituted serious threats to the two drivers of the 1920s trade boom: buoyant incomes and relatively open commercial policy.

In combination with other factors, these two forces drove world trade to a screeching halt. A trade collapse set in from 1929 to 1932 with real exports down by 49.1%, as seen in Figure 1. As both cause and effect of this drop, much of the protectionism of the 1930s was built on the foundation laid during WWI, giving rise to the substitution of exchange controls, licensing systems, and quantitative restrictions for tariffs as the primary levers of commercial policy.

Trade blocs and trade wars in the 1930s

However, the overwhelming aim of both tariff and non-tariff barriers was as a defence to the deflationary forces embedded in the global economy, particularly for those countries that remained wedded to the gold standard (Eichengreen and Irwin 2010). Thus, protectionism was exercised primarily against all trade partners and in a distinctly uncoordinated fashion with instances of bilateral retaliation being relatively minor in comparison (Gordon 1941).

Instead, bilateralism was most prevalent in the series of concessions and treaties that were signed throughout the 1930s. For instance, the Imperial Economic (or Ottawa) Conference of 1932 had as its main purpose the promotion of intra-imperial trade, primarily through preferential concessions to Commonwealth members negotiated on a strictly bilateral basis (Jacks 2014). One of the underlying goals of a number of such treaties was, then, the strengthening of existing trade blocs, primarily centred on Germany and the UK and at least partially geared towards securing food and raw materials on the basis of national security concerns (Kindleberger 1989).

Thus, the theme of trade blocs has dominated the academic literature on interwar trade (Eichengreen and Irwin 1995).

Bloc gravity in the interwar period

To isolate the effects of bloc formation on interwar trade, we consider the well-established gravity model of international trade. Over the past 20 years, the gravity model has emerged as the incontestable workhorse of empirical international trade. By now, a very large literature documents its applicability both over particular episodes in the history of globalisation and in the long run (Jacks et al. 2011). Moreover, it has been shown that gravity equations can be derived from a wide range of leading trade models.

But what do we mean by gravity? Simply that, at the bilateral level, trade is governed by the attractive force of economic mass and is mitigated by the presence of trade costs. Thus, gravity models indicate how consumers allocate expenditure across countries subject to trade frictions.

We use a data set of annual bilateral trade flows from 1920 to 1939, covering 53 countries and constituting 82% of world GDP over this period. We consider two trade blocs (the Commonwealth and the Reichsmark bloc) and two currency blocs (the gold bloc and the sterling area), also controlling for time-varying country-level features.

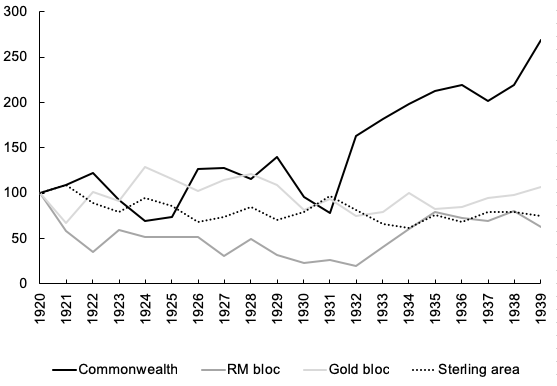

Figure 3 depicts the value of bloc dummy coefficients in every year for our four blocs – within the Commonwealth, within the Reichsmark bloc, within the gold bloc, and within the sterling area (normalised to 100 for the year 1920). The most striking observation is the rise of within-Commonwealth trade – the Commonwealth coefficient more than doubles throughout the interwar period, reaching a value of 269 in 1939. It shows a particularly strong upward trend after 1931, suggesting an intensification of trade within the Commonwealth due to the imposition of discriminatory trade policies by Britain (de Bromhead et al. 2019).

Figure 3 Bilateral trade within blocs, 1920-1939

Note: Coefficients for bloc membership by year, normalised to 1920 = 100

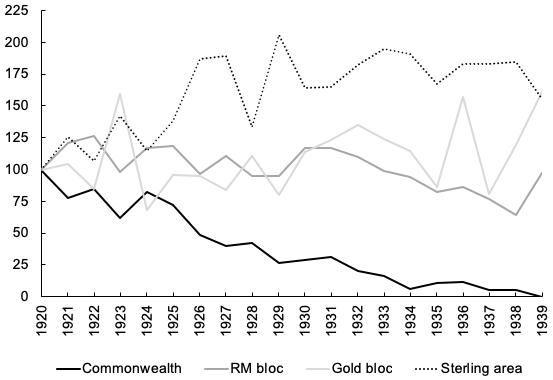

In Figure 4, we plot distance elasticities for each bloc that are allowed to vary over time. That is, we allow for a triple interaction of distance by time by bloc. Again, we normalise these coefficients to 100 for the year 1920. What is most remarkable from this figure is the fact that the distance elasticity for the Commonwealth (1) is consistently falling throughout the 1920s and 1930s in absolute magnitude, and (2) attains a value of zero in 1939.

In summary, we conclude that interwar trade patterns can be roughly characterised by two dominant observations. First, there was a persistent long-run trend towards the ‘death of distance’ in the context of bilateral trade flows within the Commonwealth, but decidedly nowhere else. Second, there were substantial increases in bilateral trade flows within both the Commonwealth and the Reichsmark bloc from 1931 and 1932, respectively. However, in the case of the Commonwealth, the trade collapse of 1929-1932 and its related trade wars seemed to only reinforce a pre-existing trend built around a surging trade bloc, spanning nearly all continents of the globe.

Figure 4 Bilateral distance elasticities within blocs, 1920-1939

Note: Value of regression coefficient for distance by year, normalised to 1920 = 100

The lessons and limits of historical parallels

We offer up some final observations, highlighting the lessons and limits of historical parallels as they relate to the notion of trade wars. First, the present day does seem to share some common features with the 1930s. In particular, there is the prospect of a formerly dominant multilateral trading system in danger of being replaced by a set of bilateral ‘deals’, initiated primarily by the current US administration. But so far, we have not witnessed a wholesale collapse of the modern trading system. This is partially due to the fact that policymakers seem to have learned some of the lessons of interwar history by not responding in a general fashion to unilateral moves toward protectionism.

This does, however, raise the prospect that the trade wars of the present day may serve the same purpose of those in the 1930s – that is, the intensification of existing and nascent trade blocs. In this vein, it requires no great imagination to see a future in which consumers’ preferences, firms’ perceptions of uncertainty, and states’ apprehensions of one another endogenously lead to a reorientation of world trade around China- and US-centric trade blocs.

The composition of trade and global value chains

Of course, one particularly telling difference of the present day from the interwar period comes from the composition of trade. The interwar trading system was still dominated by inter-industry trade. In contrast, manufactured goods now constitute the overwhelming majority of world exports, and the subsequent fragmentation of production has given rise to both a heightened sensitivity of trade flows to protectionist measures and a heightened sense of mutual interdependence across countries (Baldwin 2016). Thus, the extent to which global value chains can be unravelled arguably places limits on how far this prospective bloc-based trajectory for world trade might proceed.

References

Baldwin, R (2016), The Great Convergence: Information Technology and the New Globalization, Harvard University Press.

Bown, C, and E Zhang (2019), “Trump’s 2019 Protection Could Push China Back to Smoot- Hawley Tariff Levels”, PIIE Trade and Investment Policy Watch (May 14).

de Bromhead, A, A Fernihough, M Lampe, and K H O’Rourke (2019), “When Britain Turned Inward”, American Economic Review, 109 (2), 325-352.

Eichengreen, B, and D A Irwin (1995), “Trade Blocs, Currency Blocs and the Reorientation of World Trade in the 1930s”, Journal of International Economics, 38 (1), 1-24.

Eichengreen, B, and D A Irwin (2010), “The Slide to Protectionism in the Great Depression: Who Succumbed and Why?”, Journal of Economic History, 70 (4), 871-891.

Gordon, M S (1941), Barriers to World Trade: A Study of Recent Commercial Policy, New York: The Macmillan Company.

Jacks, D S (2014), “Defying Gravity: The 1932 Imperial Economic Conference and the Reorientation of Canadian Trade”, Explorations in Economic History, 53 (1), 19-39.

Jacks, D S, C M Meissner, and D Novy (2011), “Trade Booms, Trade Busts, and Trade Costs”, Journal of International Economics, 83 (2), 185-201.

Jacks, D S, and D Novy (2019), “Trade Blocs and Trade Wars during the Interwar Period”, CEPR Discussion Paper 13716.

Jacks, D S, and J P Tang (2018), “Trade and Immigration, 1870-2010”, NBER Working Paper 25010.

Kindleberger, C P (1989), “Commercial Policy between the Wars”, in P Mathias and S Pollard (eds.), The Industrial Economies: The Development of Economic and Social Policies, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.