What will be the impact of Brexit on UK-EU trade? A problem researchers face in addressing this question is the lack of systematic information on the content of trade agreements, which makes it difficult to precisely assess the impact that a set of common rules have on trade flows.

A way around this problem is to make assumptions on how different scenarios will lower trade costs (Dinghra et al. 2016) or to use dummies to identify trade agreements that have diverse content (Baier et al. 2008, 2014). In a recent paper, we take a different approach and use new information on the content of trade agreements to assess the impact of Brexit on goods, services, and value added trade (Mulabdic et al. 2017). Specifically, we augment a standard gravity model to quantify the effect that the ‘depth’ of EU agreements had on UK trade and then use the estimates from this analysis to evaluate the future of UK-EU trade relations under different post-Brexit scenarios.

Deep agreements

The landscape of trade and trade agreements has radically changed in the last 25 years. First, we have seen a surge in the number of preferential arrangements from 51 in 1990 to 279 in 2015. In addition, modern trade agreements are increasingly ‘deeper’ in the sense that they cover many regulatory issues and policy areas that go beyond tariffs such as services, investment, competition, and intellectual property rights protection.

Along with the change in trade institutions, the nature of trade has also dramatically changed since the early 1990s, particularly as a result of the growing internationalisation of production and the rise of global value chains (GVCs). The letter sent by the Japanese government to the UK and the EU in the aftermath of the June referendum outlining a number of requests by Japanese businesses operating in the UK on the content of a future UK-EU trade agreement illustrates the importance of a finer understanding of what Brexit entails, beyond a focus on changes in tariffs and gross goods trade flows.

The EU has been a precursor of deep integration. We use new information on the content of trade agreements from the World Bank (Hofmann et al. 2017) to build a measure of ‘depth’ based on the number of provisions covered by the agreement. The data indicate that the EU is the deepest trade agreement among the 279 currently in force covering 44 policy areas ranging from standards to movements of capital, to labour mobility (Figure 1).1

Figure 1 Average depth of trade agreements, 2015

Note: The figure shows the average depth of all the agreements signed by a country weighted by the number of partners.

Trade impact of EU membership

We first investigate the extent to which the depth of the EU contributed to boosting UK trade. We use data from the World Input Output Database (WIOD) on goods, services and value added trade and the World Bank data on the content of deep agreements to estimate a gravity equation augmented with a measure of depth for the period 1995-2011. By interacting the depth of trade agreements with dummies identifying the UK, we can quantify the effect of common trade rules on UK imports and exports of goods, services and value added.

Deep trade agreements are found to increase goods, services and value added trade -this impact has been even stronger for the UK (Figure 2). In particular, the depth of UK’s trade agreements strongly increased trade in services: as a result of its EU membership, UK services trade more than doubled. EU membership also increased domestic value added in gross exports of the UK and boosted its integration in global value chains: UK intermediates’ value added in gross exports (forward linkages) increased by 31%, while foreign value added in UK exports (backward linkages) increased by 37%.

Figure 2 Trade impacts of deep agreements

Note: The estimator is PPML. All specifications include bilateral fixed effects and country-time fixed effects. 90% Confidence intervals are constructed using robust standard errors, clustered by country-pair.

Hard versus soft disintegration

We then analyse the impact that Brexit can have on UK-EU trade relations going forward. We consider three distinct scenarios, with decreasing depth of the post-Brexit agreement between the UK and the rest of the EU. The first scenario is a ‘soft’ Brexit, assuming that the post-Brexit arrangement between the UK and the EU will be as deep as the agreement the EU has with Norway. In the second scenario, the UK and the EU will sign an agreement as deep as the average agreement the EU currently has with third countries. Finally, the third scenario has no agreement at all.

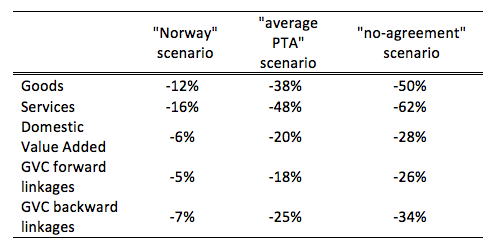

We find that bilateral UK-EU trade declines under all scenarios and that this drop is sharper the lower the depth of the post-Brexit arrangement relative to the depth of the EU agreement. In terms of value added trade, the decline ranges from 6% under the ‘softer’ Brexit scenario to 28% under the ‘harder’ scenario. The largest declines are for UK services and GVC trade (backward and forward linkages). Table 1 offers a summary of results. These predictions should be seen as average effects – an initial weak response is not a sign that bilateral trade will not change much. As it takes time for trade flows to respond to changes in trade costs, we expect the impact in the short run to be smaller than in the longer term.

Table 1 Changes in the UK’s bilateral trade with the EU under different scenarios

Notes: Depth decreases from 44 to 36 in the “Norway” scenario, to 14 in the “average PTA”, and to 0 in the “no-agreement” scenario.

Conclusions

The data point to a tradeoff between the depth of trade agreements and trade intensity. Reasons might be that deep agreements influence trade relations directly, as with services commitments that guarantee market access to the members, or indirectly as with investment, competition, and other deep provisions that make it easier to operate economic activities that span multiple borders.

This tradeoff will likely delimit future policy choices. Policymakers can either choose to undertake more binding commitments in deep agreements (a ‘soft’ Brexit) that will support more trade integration, or opt for weaker commitments (‘hard’ Brexit) and less trade. Our analysis also indicates that a shallower agreement may have a stronger negative impact on the UK’s services and GVC trade, which have relied more on the deep arrangements of the EU.

Many questions on the future of UK-EU trade relations remain open. First, the analysis does not account for the possibility that after Brexit, the UK may choose to sign new trade agreements with other trade partners, and for the EU continuing its process of “ever closer union” by further deepening its integration. How these divergent processes would impact UK-EU trade going forward is difficult to predict.

Finally, while our focus has been on the complementarity between deep trade institutions and trade flows, it could be argued that a high level of trade integration requires some form of political integration (Brou and Ruta 2008, Campos et al. 2015). Indeed, this complementarity between economic and political integration has been at the core of the European project (Padoa-Schioppa 1999). It is possible that the deepest forms of agreement may be difficult to sustain outside the Union.

Editor's Note: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and they do not necessarily represent the views of the World Bank Group or the WTO

References

Baier, S L, J H Bergstrand, P Egger, and P A McLaughlin (2008), “Do Economic Integration Agreements Actually Work? Issues in Understanding the Causes and Consequences of the Growth of Regionalism”, The World Economy 31 (4): 461–97.

Baier, S L, J H Bergstrand, and M Feng (2014), "Economic Integration Agreements and the Margins of International Trade", Journal of International Economics 93, 2.

Brou, D and M Ruta (2011), “Economic Integration, Political Integration, or Both?”, Journal of the European Economic Association, 9:6, 1143-1167.

Campos, N, F Coricelli and L Moretti (2015), “European integration: Benefits of deep versus shallow integration”, VoxEU.org, 19 June.

Dhingra, S, G Ottaviano, T Sampson and J Van Reenen (2016), “The Consequences of Brexit for UK Trade and Living Standards”, VoxEU.org, 4 April.

Hofmann, C, A Osnago, and M Ruta (2017), “Horizontal Depth: A New Database on the Content of Deep Agreements”, Working Paper, World Bank.

Mulabdic, A, A Osnago, and M Ruta (2017), “Deep Integration and UK-EU Trade Relations”, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 7947.

Padoa-Schioppa, T (1999), “Reflections on the Globalisation and Europeanisation of the Economy”, Lecture at the University of Göttingen, 30 June.

Endnotes

[1] The data can be accessed here: http://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/deep-trade-agreements