Lots of people around the world will breathe a sigh of relief at President Trump’s departure from the White House. Yet, however toxic they think his administration was in many dimensions, many might grudgingly concede that, at least until the Covid crisis, Trump presided over a particularly strong economy. Certainly, the same voters that denied him re-election thought so – up to the end they had more faith in him than in Joe Biden on the economy, and despite the pandemic the percentage that regarded his policies as helpful to the economy was higher than for Barack Obama and close to that of extremely popular presidents such as Ronald Reagan (Enten 2020). This has fuelled the legend of ‘the businessman who can at least run the economy’.

This view is wrong for two fundamental reasons. The first is that Donald Trump is far from a successful entrepreneur. He started doing business with his father’s money, and although he never declared personal bankruptcy, his businesses entered bankruptcy proceedings six times and he was rescued by his father on many occasions (e.g. Kranish and Fisher 2016). According to Bartsow et al. (2018), at several critical junctures he received a total of at least $413 million from his father via a stream of 295 contributions, which he used to buttress his failing businesses, starting from the ill-fated extravagant takeover of Atlantic City. He also used another half a billion dollars from his entertainment business (mostly from The Apprentice and related activities) to subsidise his other failing investments. But this source of income is gone too. His brand name (an intangible) – which in 2013 he valued at an outlandish $4.1 billion dollars when making an application for a loan (Enrich et al. 2019), only to value it at almost zero when filing his tax returns – is arguably now worth little after the recent events. He now faces at least $400 million of personal debt coming due in the next three years, and several financial institutions have already announced that they will no longer do business with him. Not to mention the enormous costs of a possible negative outcome of his IRS audit, or of the two legal proceedings for tax evasion that he faces in the State of New York (Buettner and Craig 2021). Given the opacity of Donald Trump’s operations, we might have to wait for the conclusion of these tax evasion trials to have a better idea of his net wealth, but it is not implausible that we will learn that he eroded a good part of the net wealth bequeathed to him by his father, while at the same time claiming to be a self-made man.

Second, and most importantly, the American economy did not do so well under Trump even before the Covid-19 crisis. Of course there is an immense debate about the pros and cons of the Trump administration for the economy (for an example in the economics press, see Ponnuru and Smith 2020). To take one example among many, even sworn enemies of Trump like The Guardian have come to acknowledge that his first three years were very good – comparable to, if not better than, the Obama years (Eliot 2021). Others acknowledge that he rode the wave of an already strong economy under Obama, but that, for instance, “consumer spending has been one of the strongest features” (Fox and Politi 2020). There has also been a huge debate on the effects of his trade dispute on manufacturing jobs.

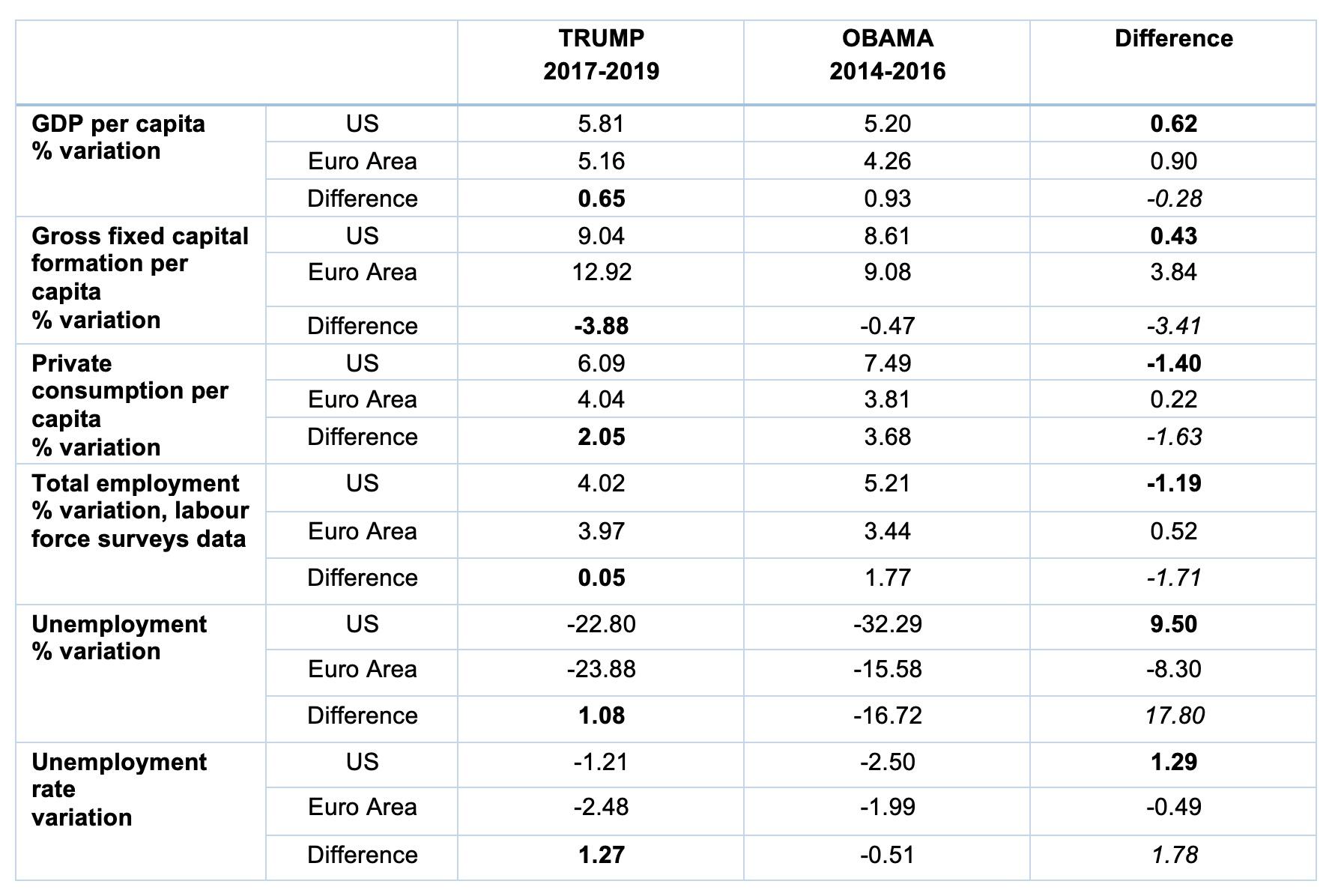

We take a purely macroeconomic perspective and a simple (perhaps simplistic) methodology. We compare the performance of macroeconomic variables such as GDP growth, gross fixed capital formation, private consumption, employment, and unemployment over the first three years of the Trump administration (2017-2019; for obvious reasons we leave out 2020) and the last three years of the Obama administration (2014-2016). We also make the same comparison relative to the euro area – not usually considered a star performer over that period – during the first three Trump years.1 Finally, we compare the first difference with the second difference – a simple difference-in-differences exercise.

The results are displayed in Table 1, which is organised as follows. The first row under each heading (GDP growth, gross fixed capital formation, etc.) displays the US both under Trump (first column) and under Obama (second column), while the second row displays the euro area over the same time periods. The difference between Trump and Obama is displayed in bold in the third column, and the difference between Trump and the euro area is displayed in bold in the third row. The last cell on the right-hand side of the third row, in italics, displays a difference-in-difference: (Trump less euro area) – (Obama less euro area). This is meant to partial out worldwide effects that might influence the difference between Trump and Obama. All the data come from the latest issue of the OECD Economic Outlook database.

Table 1

Five facts stand out. First, per capita GDP growth was only mildly stronger under Trump than under Obama or in the euro area (+0.2 percentage points on a yearly basis) – and the euro area is not usually considered a star performer during the Trump years. Second, in terms of gross fixed capital formation (investment before depreciation), Trump did worse than the euro area and only mildly better than Obama. Note that boosting private investment was perhaps the key argument made by Trump in support of his tax reform which favoured the very rich by reducing the taxation of profits. Third, private final consumption did worse under Trump than under Obama. Unfortunately, data on income distribution after taxes and transfers, which would be useful, inter alia, to understand if this difference can be attributed to redistribution favouring households with a lower propensity to consume, are not yet available. Fourth, the labour market did better under Obama and in the euro area than under Trump. The unemployment numbers – both the levels and relative to the labour force – are particularly striking in this respect.2

Fifth, and perhaps most interestingly, the last cell of each panel shows that compared to the euro area, Obama did better than Trump in all variables.

So, where does the perception that Trump was particularly good for the economy come from? A possible reason is the tendency to interpret the stock market performance as a measure of economic activity. Nasdaq jumped by 140% over the course of the Trump administration, twice as much as under Obama’s second administration. The performance of the Dow Jones (+57%) was slightly better under Trump, while European stocks did much worse (Frankfurt: +20%; Eurostoxx50 index: +10%).

It is well known that Trump eagerly followed the daily performance of the stock market as a measure of the health of the US economy. This is another indication of his incompetence – 84% of American stocks are owned by the individuals in the top decile of the income distribution (Wolff 2017). Furthermore, a lesson from the Great Recession, and even more so from the Covid-19 crisis, is that the performance of the stock market can be largely independent of underlying economic performance, notably when central banks massively inject liquidity and interest rates are close to zero or negative.

The real danger behind the view that Trump was good for the economy is that it suggests that economic policy can be best handled by entrepreneurs. This view paved the way for the electoral success of Berlusconi in Italy, who brought Italy to the brink of collapse at the time of the 2011 debt crisis – in part caused by the behaviour of the Berlusconi government itself. The lesson that Italians (and hopefully Berlusconi as well) have learnt from that experience is that there is virtually no relationship between running a country and managing a company.

Now Joe Biden will have to deal with President Trump’s legacy. The $2 trillion package announced by Biden goes in the right direction, but it mistakenly allows for a $2,000 transfer to all families with a joint income of up to $75,000 and phasing it out progressively above this threshold, rather than concentrating federal support on the truly needy. This gross wastage of public resources is another legacy of Trump’s incompetence in economic policy. Just before Christmas he rejected – as always, via Twitter – the stimulus package sent by Congress on the grounds that it contained too much “pork” (i.e. spending items unrelated to the Covid crisis). He did not realise, however, that to save time Congress had sent him the Federal budget together with the stimulus bill. Then, on a whim of the moment and in an act of pure demagoguery, he decided – again, on Twitter – to increase the transfer from $600 to $2,000. Just before the Georgia elections, this left the Democrats little choice but to follow him. Biden would do well to reconsider this choice. There is no such a thing like a soft budget constraint, and in an emergency like this it would be much more effective to concentrate resources on the many Americans who have been left out in the cold by the pandemic.

References

Bartsow, D, R Buettner, and S Craig (2018), “Trump Engaged in Suspect Tax Schemes as He Reaped Riches From His Father”, New York Times, 2 October.

Buettner, R and S Craig (2021), “The Financial Minefield Awaiting an Ex-President Trump”, New York Times, 19 January.

Economist (2020), “How the American economy did under Donald Trump: An international comparison", 17 October.

Elliot, L (2021), “Trump saw the economy was his ticket to a second term – then Covid struck”, The Guardian, 15 January.

Enrich, E, M Goldstein and J Drucker (2019), “Trump Exaggerated His Wealth in Bid for Loan, Michael Cohen Tells Congress”, New York Times, 27 February.

Enten, H (2002), “How Trump Won the Economic Message Battle”, CNN Politics, 25 December.

Fox, B and J Politi (2020), “The rise and fall of the Trump economy in charts”, Financial Times, 4 November.

Kranish, M and M Fisher (2016), Trump Revealed, Simon and Schuster.

Ponnuru, R and K W Smith (2020), “Did Trumponomics Actually Beat Obamanomics?”, Bloomberg, 21 November.

Smith, K W (2020), “Trump’s Economy Really Was Better Than Obama’s”, Bloomberg, 20 October.

Wolff, E (2017), “Household wealth trends in the united states, 1962 to 2016: has middle class wealth recovered?”, NBER Working Paper No. 24085.

Endnotes

1 This exercise is similar to one performed recently by The Economist (2020), which compared the performance of GDP growth and of business investment with the forecasts made at the beginning of the Obama and of the Trump presidencies, and with the median G6 performance.

2 A Trump supporter would argue that he inherited a labour market close to full employment, and that it was difficult to further reduce the unemployment rate (e.g. Smith 2020). However, there was still a large inactivity rate to reabsorb and Trump also did worse than Obama on employment.