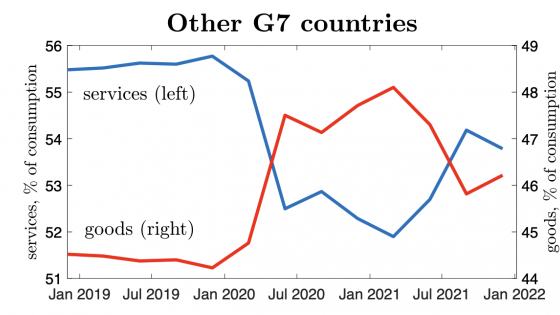

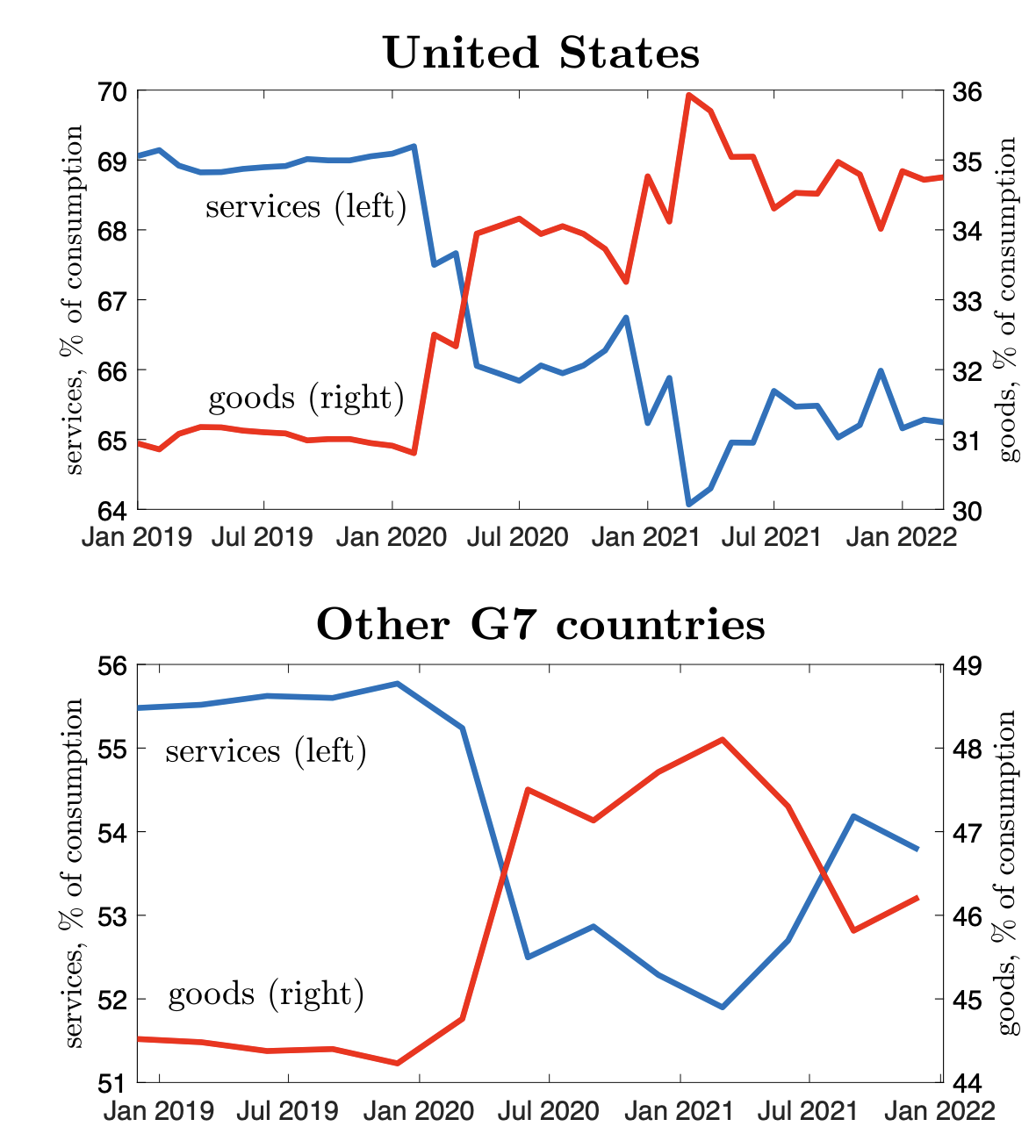

A salient feature of the ongoing recovery from the Covid-19 recession is its unbalanced nature. Throughout the world, demand for goods is buoyant, while demand for contact-intensive services is subdued (Figure 1). Considering that goods are typically traded across countries while most services are not, the global economy is effectively experiencing a large reallocation of demand away from non-tradable services and towards tradable goods. Unsurprisingly, this period of exceptionally high global demand for goods is associated with rising goods prices, and stress on the global supply chains (Eo et al. 2022).

Figure 1 Goods and services share in total consumption expenditure

Note: See Fornaro and Romei (2022a) for data sources.

In a recent paper (Fornaro and Romei 2022a), we propose a multi-country Keynesian model with multiple sectors to understand the macroeconomic implications of this unusual demand pattern. Our analysis is organised around three questions: What is the optimal monetary policy response to a reallocation of global demand from services to goods? How are international spillovers shaping the global recovery and the inflation outlook? Are there gains from international cooperation?

Monetary policy and the structuralist approach to inflation

We study a world composed of countries producing tradable goods and non-tradable services. Nominal wages are rigid, so that monetary policy has real effects, and involuntary unemployment may arise due to weak demand. We consider a global reallocation shock, that is, a temporary rise in consumers' demand for goods relative to services, leading to an increase in the share of consumption expenditure on goods similar to the one observed during the pandemic.

Our first insight is that this reallocation of demand from services to goods can push the global economy into stagflation. Intuitively, lower demand induces firms in the service sector to reduce production and fire part of their workforce. To contain the increase in unemployment, a rise in inflation in the traded sector is needed. On the one hand, higher prices induce firms in the goods sector to hire more workers and increase production. Moreover, as workers receive more income from the tradable sector, their demand for services rises.1 Through this income effect, higher goods prices lift employment in the service sector too.

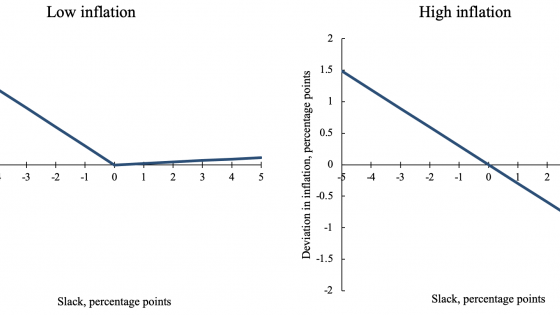

The optimal monetary policy trades off the costs arising from high inflation against the employment gains.2 A reallocation shock thus acts as a cost-push shock, leading to a contemporaneous rise in inflation and unemployment. These results are in line with the structuralist view of inflation (Olivera 1964, Tobin 1972, Guerrieri et al. 2021), which argues that some inflation is needed to reallocate smoothly workers across different sectors. This literature, however, has mainly focused on closed economies, while we are interested in its international implications.

Capital flows, trade imbalances, and inflationary spillovers

In a financially integrated world, a country can increase its consumption of traded goods by borrowing from the rest of the world and running trade deficits. Indeed, in our model the regions experiencing the strongest increase in demand for traded goods adjust by running trade deficits toward the rest of the world. This helps explain why the US trade balance deteriorated during the recovery from the Covid-19 recession, since in the US the rise in goods consumption has been particularly pronounced.

Trade deficits, however, generate international inflationary spillovers. When a country runs a trade deficit, it exacerbates the scarcity of tradable goods on the global markets and worsens the trade-off between inflation and employment in the rest of the world. Through this channel, a country experiencing a rise in its demand for tradable goods exports high inflation abroad.

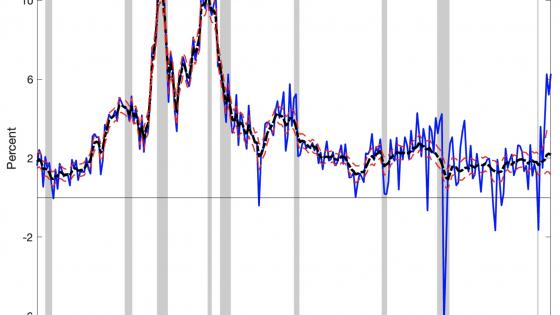

Our work thus formalises the notion that global factors are playing an important role in the recent rise in inflation, which was largely synchronised among advanced economies (Forbes et al. 2021). It also warns against the use of inflation differentials to measure the strength of relative demand, say between the US and the euro area. The reason is that high goods demand in the US, and the associated trade imbalances, lifts inflation in the euro area too. A more complete approach to understanding demand differentials should thus look at a combination of inflation and trade imbalances.

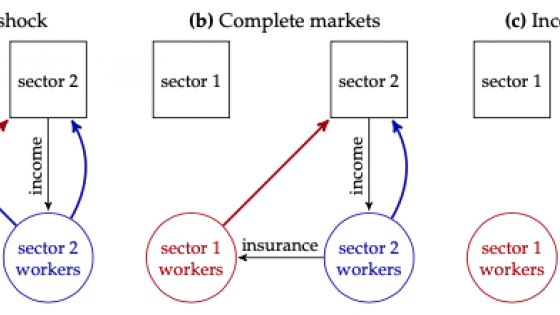

Free riding and gains from monetary policy cooperation

We also highlight the presence of a free riding problem among national central banks, arising when global demand for tradable goods is exceptionally high. When a country implements a monetary expansion, it fosters its production of traded goods and increases its net exports toward the rest of the world, thus easing pressure on the global markets for tradables. As global consumers gain access to a greater supply of tradable goods, their demand for non-tradable services rises. Through this channel, a monetary expansion lifts aggregate demand and employment not only domestically, but in the rest of the world as well.

The presence of this international aggregate demand spillover implies that national central banks are likely to fall in a coordination trap. The reason is simple. The inflation costs associated with monetary expansions are fully borne by domestic agents. The gains in terms of higher demand and employment, instead, are partly enjoyed by the rest of the world. National monetary authorities have thus an incentive to free ride on foreign monetary expansions, meaning that lack of international cooperation may lead to excessive unemployment during periods of exceptionally high demand for tradable goods.

This result is connected to the debate on the international externalities triggered by countries running large trade surpluses. A long tradition argues that current account surpluses are detrimental when global demand is scarce, because they export abroad domestic demand weaknesses.3 But we show that things are very different when global demand for tradable goods is high, such as during the recovery from the Covid-19 recession. In this case, policies that foster the domestic production of tradable goods – and current account surpluses – alleviate the pressure on the global goods market, and act as a benign disinflationary force on the rest of the world. These considerations suggest that current account surpluses should be discouraged when global demand is weak but encouraged when the weakness is on global supply. Of course, this makes designing a system to regulate international trade imbalances a daunting task.

Energy shocks in the global economy

Partly due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, global energy prices are rising fast. In ongoing work (Fornaro and Romei 2022b), we show that a rise in energy prices exacerbates all the stagflationary forces described above. High energy prices, in fact, increase production costs for manufacturing firms, leading to a global scarcity of tradable goods. As discussed above, when traded goods are scarce, central banks face a trade-off between inflation and employment, trade deficits impose deflationary spillovers toward the rest of the world, and monetary expansions produce positive demand spillovers in foreign countries. The main difference is that in this case the euro area, due to its dependence on Russian energy, is likely to be the worst hit region, meaning that the ECB may face a particularly harsh trade-off between containing inflation and sustaining economic activity.

References

Eo, Y, L Uzeda, and B Wong (2022) “Goods inflation is likely transitory, but upside risks to longer-term inflation remain”, VoxEU.org, 29 April.

Fornaro, L and F Romei (2019), “The paradox of global thrift”, American Economic Review 109(11): 3745-79.

Fornaro, L and F Romei (2022a), “Monetary policy during unbalanced global recoveries”, CEPR Discussion Paper 16971.

Fornaro, L and F Romei (2022b), “Energy shocks in the global economy”, forthcoming.

Forbes, K, J Gagnon, and C Collins (2021), “Pandemic inflation and nonlinear, global Phillips curves”, VoxEU.org, 21 December.

Guerrieri, V, G Lorenzoni, L Straub, and I Werning (2020), “Viral recessions: Lack of demand during the coronavirus crisis”, VoxEU.org, 6 May.

Guerrieri, V, G Lorenzoni, L Straub, and I Werning (2021), “Monetary policy in times of structural reallocation”, University of Chicago, Becker Friedman Institute for Economics Working Paper No. 2021-111.

Olivera, J H (1964), “On structural inflation and Latin-American ‘structuralism’”, Oxford Economic Papers, 321-332.

Tobin, J (1972), “Inflation and unemployment”, American Economic Review 62(1): 1–18.

Endnotes

1 Guerrieri et al. (2020) emphasise the role of demand complementarities across different sectors during the Covid-19 pandemic.

2 In the model, inflation imposes a direct utility loss on agents. This is meant to capture a variety of costs linked to high inflation, such as undesirable redistribution across individuals, or the risk that the economy loses its nominal anchor.

3 This idea underlies Keynes' plan of 1941, which envisaged penalties for countries running persistent surpluses. In Fornaro and Romei (2019), we formalised this insight and argued that these dynamics were likely at play in the decade following the 2008 financial crisis.