The design of social insurance and welfare programmes is a complex balancing act. Policymakers aim to target social transfers to individuals who need them the most. One way of achieving this goal is to restrict the receipt of transfers to people exposed to specific conditions, or to the occurrence of particular events (i.e. ‘bad shocks’ such as health issues, disability, or unemployment). The idea is that people value transfers highly when subject to these shocks. Still, there may be tremendous variation in the value of receiving transfers. How, then, can we improve targeting?

A classic approach in economics to elicit individuals’ valuations is by letting them choose. But in practice, social insurance programmes leave remarkably little choice to their beneficiaries. Individuals are mandated to pay social security contributions; in return, they get pension benefits, coverage of health expenditures, disability and unemployment benefits, and so on. These social transfers may depend on different characteristics of the beneficiaries, and how much they were mandated to contribute in particular, but otherwise the levels are beyond their control. The transfers can often be complemented – think of tax-favoured retirement savings or private top-ups of health insurance – but in many instances the room for choice does not exist at all.

Unemployment insurance (UI), for example, is compulsory in almost all countries and no choice is given to workers over how much coverage to get. But why restrict choice, given that it can improve the targeting of individuals who value UI the most? The main rationale underlying the UI mandate is the potential for adverse selection – only workers who face high unemployment risk would buy UI. Adverse selection could thus put pressure on any market or system that leaves choice to individuals, and potentially lead to full unravelling a la Akerlof. To see whether it actually would, we need to look beyond the ‘lamp post’. While a long literature, both theoretical and empirical, has analysed how to design mandatory UI, the question of whether we should actually mandate UI has not been explored (Chetty and Finkelstein 2013).

Voluntary insurance in Sweden

In a recent paper, we study whether adverse selection can indeed rationalise the universal mandate of the generous UI programmes we see in most European countries (Landais et al. 2017). We exploit an exceptional setting in Sweden in combination with rich, administrative data on UI choices and unemployment histories. All Swedish workers are entitled to a minimum, flat benefit level when unemployed, but can opt to buy income-related UI. This voluntary UI programme – also in place in Denmark, Finland, and Iceland – stems from the UI funds originally set up by trade unions. Around 80% of workers in Sweden opt for the income-related comprehensive insurance. To become eligible, a uniform premium (independent of income) needs to be paid for twelve months. This premium was heavily subsidised up to 2007, when a newly elected right-wing government tripled the price.

Positive correlation tests

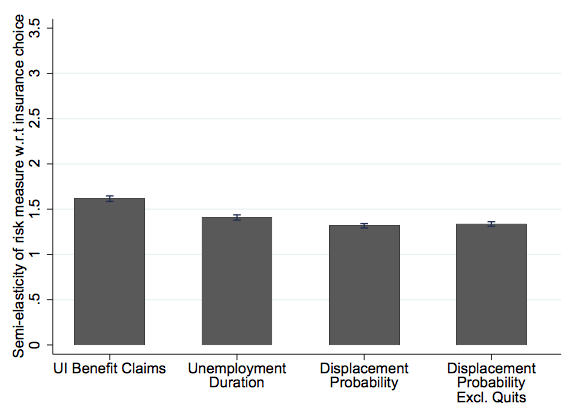

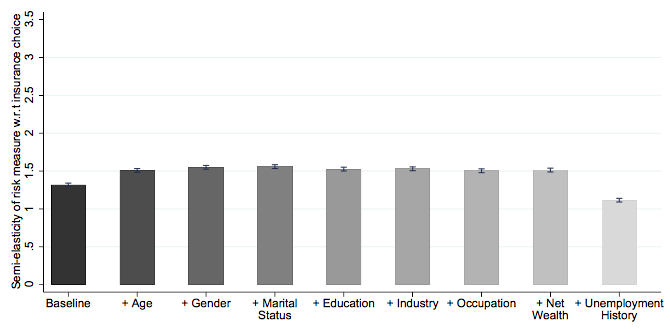

A prominent literature studying adverse selection in insurance markets has focused on so-called positive correlation tests (Chiappori and Salanié 2000) which, applied to the UI context, test whether workers who choose to buy more coverage are more likely to be unemployed. Figure 1 shows a large positive correlation – workers buying the income-related UI in year t are more than twice as likely to be unemployed in year t+1. Interestingly, the large difference is robust to various measures of unemployment risk and to the introduction of a rich set of controls, which could potentially be priced. As shown in Figure 2, even when absorbing the variation in unemployment risk coming from differences in age, education, industry, occupation, and so on, workers' choices remain strongly correlated with unemployment risk. This suggests strong asymmetries in information that cannot be priced.

Figure 1 Positive correlation tests, baseline

Notes: The figure displays the correlation between UI coverage and unemployment risk. The estimates can be interpreted as percentage increases of the unemployment risk for individuals buying comprehensive insurance compared to those who don’t. The four measures of risks are: (i) total UI claims under comprehensive coverage, (ii) time spent unemployed, (iii) probability of displacement, and (iv) probability of displacement excluding voluntary quits. We also control for the limited set of characteristics that affect individuals’ price and coverage.

Figure 2 Positive correlation tests: The role of unpriced heterogeneity

Notes: The figure displays the correlation between UI coverage and unemployment risk, using the probability of displacement in t+1. Each column to the right of the baseline adds a further set of controls to the baseline specification of Figure 1. We start by adding demographic controls (age, then gender, and marital status), then control for skills and other labour market characteristics (controls for education, industry, occupation) and wealth level (quartiles). We finally add controls for past unemployment history (dummies for having been unemployed in t-1, t-2, and up to t-8).

Separating adverse selection

That workers with more coverage are more likely to be unemployed can also be driven by moral hazard rather than by adverse selection. Estimating the incentive costs of UI has been the central theme of a prominent literature (Schmieder and Von Wachter 2016). Disentangling moral hazard and adverse selection is a well-known challenge, but it is of first-order importance since moral hazard by itself does not rationalise a universal mandate, and can be controlled by reducing the generosity of the insurance.

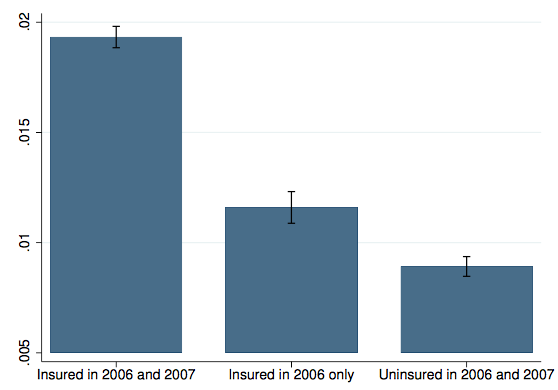

In the Swedish context, the large premium increase in 2007 allows for a direct test of adverse selection (Einav et al. 2010) as we can compare the unemployment risk of workers who differ in revealed willingness to pay, but have the same insurance coverage. Figure 3 shows the unemployment risk for three groups of workers: workers who stayed on comprehensive UI despite the price increase (76%), workers who switched out of comprehensive UI after the price increase (8%), and workers who were on basic UI even before the price increase (16%). The latter two groups of workers have only basic coverage in 2007. While subject to the same incentives, the switchers who valued the comprehensive coverage above the pre-2007 premium are 25% more likely to be unemployed than those who didn’t buy the coverage in either year. In our paper, we provide further evidence that workers also change their UI choice in response to changes in their unemployment risk.

Figure 3 Unemployment risk by willingness to pay

Notes: The figure uses the 2007 price reform to rank individuals according to their willingness-to-pay for the comprehensive coverage, and shows the probability of displacement in 2008 by willingness-to-pay. The group on the left are individuals who buy comprehensive coverage both in 2006 and 2007 and have the highest level of willingness to pay. The middle group are individuals who buy the comprehensive coverage in 2006 but switch out in 2007 when the premium increases. They have higher willingness-to-pay than the last group on the right, of individuals who buy the comprehensive coverage neither in 2006, nor in 2007.

Universal mandate?

Our study demonstrates the importance of adverse selection in UI choices, and corroborates the evidence in Hendren (2017) that private information about unemployment risks (as elicited through surveys) may be detrimental to private UI markets. A universal mandate, excluding any choice, naturally combats adverse selection. However, it comes at the cost that workers are forced to buy insurance even when they value it below cost. In Sweden, the estimated average cost of providing comprehensive insurance to job seekers who decide not to buy it at the low pre-2007 price is above their valuation. Hence, forcing them to buy comprehensive coverage would reduce welfare, assuming that no other frictions underlie their low valuation (ee Ericson and Sydnor 2017, Finkelstein et al. 2017).

Allowing for choice

The question then becomes how to allow for more choice in a setting where workers risk being priced out of suitable insurance. A first simple response is to subsidise the prices of more comprehensive insurance and improve the pool of risks these plans attract. A second, complementary response is to introduce a minimum mandate, which mitigates the loss of being priced out of comprehensive insurance. How to set these instruments will crucially depend on the interplay between insurance value, moral hazard costs, and selection effects, as we show in our paper. Importantly, the Swedish unemployment system combines these instruments already and by doing so provides a lamp post that allows light to be shed on these effects.

References

Chetty, R, and A Finkelstein (2013), “Social insurance: Connecting theory to data”, in A J Auerbach, R Chetty, M Feldstein and E Saez (eds.) (2013), Handbook of public economics. vol. 5, 111-193, North Holland.

Chiappori, P A, and B Salanie (2000), “Testing for asymmetric information in insurance markets”, Journal of political Economy 108(1): 56-78.

Einav, L, A Finkelstein, and M R Cullen (2010), “Estimating welfare in insurance markets using variation in prices”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 125(3): 877-921.

Ericson, K, and J Sydnor (2017), “The Questionable Value of Having a Choice of Levels of Health Insurance Coverage”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 31(4): 51-82.

Finkelstein, A, N Hendren, and M Shepard (2017), “Subsidizing Health Insurance for Low-Income Adults: Evidence from Massachusetts”, working paper.

Hendren, N (2017), “Knowledge of future job loss and implications for unemployment insurance”, American Economic Review 107(7): 1778-1823.

Landais, C, A Nekoei, P Nilsson, D Seim, and J Spinnewijn (2017), “Risk-based Selection in Unemployment Insurance: Evidence and Implications”, working paper.

Schmieder, J F, and T von Wachter (2016), “The Effects of Unemployment Insurance: New Evidence and Interpretation”, Annual Review of Economics 8: 547–581.