Does urban concentration spur economic growth? According to dominant views, urban concentration is deemed to produce a wide range of benefits. It is linked to reductions in poverty (Sekkat 2017), pollution (Makido et al. 2012) and inequality (Castells-Quintana and Royuela 2015, Oyvat 2016), but, more consistently, to the formation of agglomeration economies and productivity gains, which, in turn, lead to greater national economic growth (for an overview, see Martin 2008). More concentrated urban structures – in particular at low levels of development – are frequently regarded as growth enhancing (Brülhart and Sbergami 2009, Henderson 2003, World Bank 2009).

However, this perception may be built on thin ice. Two factors point in this direction. First, there is limited information about how urban concentration has evolved across different countries in the world. The majority of studies on the topic analyse what drives the city size distribution within countries (Anthony 2014). The few that analyse patterns are either cross-sectional (e.g. Short and Pinet‐Peralta 2009) or focus on a specific country or region (e.g. Aroca and Atienza 2016, Behrens and Bala 2013). Second, levels of urban primacy – that is, the concentration of a country’s urban population in the largest city (Anthony 2014, Behrens and Bala 2013, Henderson 2003) or the share of the urban population living in cities above a certain size threshold (Brülhart and Sbergami 2009, Sekkat 2017) – are used, but these are poor indicators of urban concentration.

In a recent article, we address these shortcomings in the relationship by assembling an entirely new dataset – which permits the construction of more nuanced indicators of urban concentration for a large number of countries – and examine how the level of urban concentration has evolved between 1985 and 2010 across a large set of countries (Frick and Rodríguez-Pose 2018). We then turn to how changes in urban concentration have affected economic growth in the same time period, paying particular attention to differences in impact between developed and developing countries.

Testing the link between city size and economic growth

Using census data for each country available on citypopulation.de, and complementing it with information from the 2014 edition of the World Urbanization Prospects (United Nations 2014), we build a new city population dataset from scratch. The dataset covers 68 countries over the period 1985 to 2010. Armed with these data, we construct three different Herfindahl-Hirschman indices (HHI) as our measures of urban agglomeration. The first index (HHI50) includes all cities of a country with 50,000 or more inhabitants; the second (HHI100), all cities with 100,000 inhabitants or more; and the final one (HHIrank) includes the 25 largest cities, independent of their size. These indices are employed to analyse the evolution of urban concentration from 1985 to 2010.

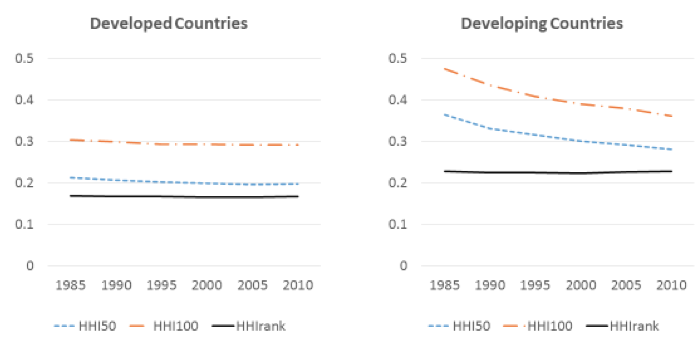

Figure 1 Evolution of urban concentration in developed and developing countries, 1985- 2010

The average of the different HHIs, dividing the sample into developed and developing countries, are plotted in Figure 1. Three insights emerge.

- First, developed countries have much less concentrated urban structures than developing countries. The difference is particularly marked for HHI50 and HHI100 indicators, despite a significant decrease in urban concentration for developing countries over the last three decades.

- Second, the average levels of concentration have remained relatively stable for developed countries but have changed dramatically in developing countries. While the average level of HHI50 and HHI100 in developing countries was higher than in developed countries, it decreased sharply in the former (from 0.36 to 0.28 and 0.48 to 0.36 respectively), pointing to a declining concentration of the urban population. Rapid urbanisation processes in the emerging world are behind this trend. The number of people living in cities doubled in middle-income countries between 1985 and 2010, and almost tripled in the least developed countries. This has resulted in the birth of new cities and rapidly growing urban populations across the spectrum of city sizes.

- Finally, there are differences between the indicators in terms of their evolution. The average of the HHI50 and HHI100 indicators declined – albeit at a different pace – for both developed and developing countries, suggesting lower concentration levels. In contrast, the average HHIrank indicator remained stable for both groups of countries.

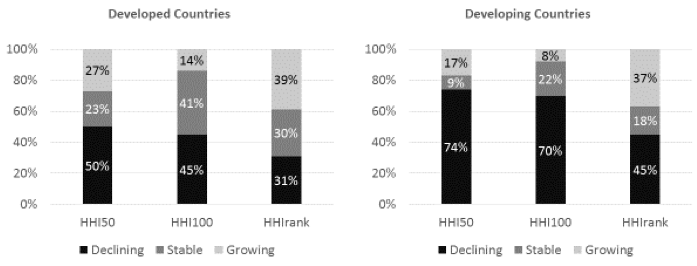

Considerable heterogeneity can be found within both country groups. Figure 2 shows the percentage of developed and developing countries in which the different indicators either displayed a declining, a stable or a growing urban concentration. In developed countries, there was considerable diversity in urban concentration. Yet, according to HHI50 and HHI100, more countries had less concentrated urban structures in 2010 compared to 1985. The HHIrank indicates, however, that almost four out of ten developed countries had more concentrated urban structures in 2010 than in 1985. Only three out of ten had less concentration.

Figure 2 Evolution of urban concentration in developed and developing countries, 1985-2010

Among developing countries, the picture is more homogenous. Driven by increasing urbanisation rates and a general increase in the size of cities, an overwhelming majority of the countries became less concentrated during the period of analysis (as measured by HHI50 and HHI100). Urban concentration decline was strongest across Latin America. Many Asian countries, in contrast, had increasing levels of urban concentration. One in two Asian countries is more concentrated today than in 1985. In Africa the picture differs strongly depending on the indicator chosen.

Urban concentration and economic growth

How have changes in urban concentration at the national level affected economic growth? The analysis of the link between urban concentration and economic growth suggests that, contrary to the dominant view, there is no uniform relationship between both factors. Urban concentration has been beneficial for economic growth in high-income countries, but this effect – in line with Pholo-Bala (2009) and Castells-Quintana (2017) – does not hold for developing countries. This contrasts with some of the most prominent previous studies (e.g. Bertinelli and Strobl 2007, Brülhart and Sbergami 2009, Henderson 2003) and especially with those that reported a particularly important effect for low levels of economic development. For lower levels of economic development, urban concentration seems to be wholly disconnected from a country’s economic performance. Continued high levels of urban concentration have gone hand in hand with ever increasing city sizes in developing countries. While the average size of the largest city in each country grew by around 20% between 1985 and 2010 in developed countries, the size of the largest city in a given developing country more than doubled in the same period, from an average of 1.8 million to 4 million inhabitants (numbers based on United Nations 2014). The relative growth of city size in developing countries was similar for the period between 1960 and 1985 (from an average of 0.85 million to 1.8 million), but the absolute increases as well as the levels became much larger in the latter period. This development may lead to a prevalence of urban diseconomies of scale – congestion, pollution, emergence of large slums – as well as other diseconomies, such as inequality and social and political conflict (Rodríguez-Pose 2018). Urban diseconomies may thus largely undermine any positive effects from the concentration of economic activity.

What are the implications of these results for policymakers who face the question of whether to promote further agglomeration or to stimulate development outside of the primary urban areas?

As with most questions, there is no easy answer. On the one hand, the results show that, despite decreasing levels of urban concentration in many developing countries, urban concentration remains high and many countries saw their levels increase. Urban concentration may, thus, not be self-correcting with economic development as frequently hypothesised. Furthermore, the analysis dispels the prevailing notion that a more concentrated urban structure is best for economic growth, in particular at low levels of economic development (e.g. World Bank 2009). While no uniform relationship can be deduced, the results show that many countries in the developing world are likely to suffer more from congestion generated through increased concentration than benefit from it. Hence, promoting development outside of primary urban areas would be beneficial from an economic point of view.

On the other hand, developed countries with the right urban infrastructure in place and an economy with industries strongly benefiting from agglomeration economies highlight that certain countries can, in fact, benefit from urban concentration. This suggests that sweeping policy recommendations may be ill-advised and that more specific, country-based research may be the way forward in order to set up policies that may foster and make best use of the economic potential of cities and urban agglomeration on a case by case basis.

References

Aroca, P and M Atienza (2016), “Spatial concentration in Latin America and the role of institutions”, Investigaciones Regionales 36: 233-253.

Behrens, K and A P Bala (2013), “Do rent‐seeking and interregional transfers contribute to urban primacy in Sub‐Saharan Africa?” Papers in Regional Science 92(1): 163-195.

Bertinelli, L and E Strobl (2007), “Urbanisation, urban concentration and economic development”, Urban Studies 44(13): 2499-2510.

Brülhart, M and F Sbergami (2009), “Agglomeration and growth: Cross-country evidence”, Journal of Urban Economics 65(1): 48-63.

Castells-Quintana, D (2017), “Malthus living in a slum: Urban concentration, infrastructure and economic growth”, Journal of Urban Economics 98: 158-173.

Castells-Quintana, D and V Royuela (2015), “Are increasing urbanisation and inequalities symptoms of growth?” Applied Spatial Analysis 8(3): 291-308.

Frick, S A and A Rodríguez-Pose (2018), “Change in urban concentration and economic growth”, World Development 105: 156–170.

Henderson, J V (2003), “The urbanization process and economic growth: The so-what question”, Journal of Economic Growth 8(1): 47-71.

Makido, Y, S Dhakal and Y Yamagata (2012), “Relationship between urban form and CO2 emissions: Evidence from fifty Japanese cities”, Urban Climate 2: 55-67.

Martin, R (2008), “National growth versus spatial equality? A cautionary note on the new ‘trade-off’ thinking in regional policy discourse”, Regional Science Policy & Practice 1(1): 3-13.

Oyvat, C (2016), “Agrarian structures, urbanization, and inequality”, World Development 83: 207.

Pholo-Bala, A (2009), “Urban concentration and economic growth: Checking for specific regional effects”, Center for Operations Research and Econometrics (CORE), Université Catholique de Louvain, Discussion Paper 2009/38.

Rodríguez-Pose, A (2018), “The revenge of the places that don’t matter (and what to do about it)”, Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 11(1).

Sekkat, K (2017), “Urban concentration and poverty in developing countries”, Growth and Change 48: 435–458.

Short, J R and L M Pinet‐Peralta (2009), “Urban primacy: Reopening the debate”, Geography Compass 3(3): 1245-1266.

United Nations (2014), World Urbanization Prospects: The 2014 Revision.

World Bank (2009), World Development Report 2009. Reshaping Economic Geography, Washington, DC: World Bank.