A unique feature of the global policy response to the crisis is that, as part of their efforts to boost aggregate demand and growth, some governments adopted expansionary policies that also incorporated a sizable "green fiscal" component. Such measures have been wide ranging, including support for renewable energy, carbon capture and sequestration, energy efficiency, public transport and rail, and improving electrical grid transmission, as well as other public investments and incentives aimed at environmental protection.

Of the $3.3 trillion allocated worldwide to fiscal stimulus over 2008-9, $522 billion was devoted to such green expenditures or tax breaks (Robins et al. 2009 and 2010). Almost the entire global green stimulus has been provided by the world's twenty largest and richest countries, the G20.

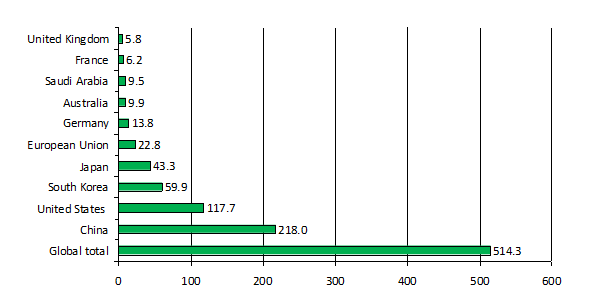

As Figure 1 shows, the US and China accounted for over two-thirds of the global expenditure on green fiscal stimulus during 2008 and 2009. The world's largest economy, the EU, contributed substantially less to the global total. Total green spending by all of Europe totalled only $57 billion; in contrast, the Asia Pacific region spent $342 billion (Robins et al. 2010). The governments of key European economies, such as France, Germany, and the UK, spent much less on clean energy and other environmental investments than the major Asia-Pacific economies, i.e. Japan and South Korea. Several G20 governments commit no – or only very few – funds to green stimulus, including the large emerging market economies of Brazil, India, and Russia

Figure 1. Global green stimulus spending, from September 2008 through December 2009 ($ billions)

Source: Barbier (2010); Robins et al. (2009); Robins et al. (2010).

As shown in Figure 2, green measures and investments amounted globally to around 16% of all fiscal stimulus spending during the recession. However, only a handful of economies devoted a substantial amount of their total fiscal spending to green initiatives. The most notable is South Korea, which allocated nearly 80% of its total expenditure to green investments. China apportioned around a third of its total fiscal spending to green measures. Around 60% of the EU's fiscal stimulus was for green investments, but as indicated in Figure 1, the overall size of this investment was relatively small. In comparison, whereas the US total expenditure on green stimulus was large, it comprised only 12% of total fiscal spending. Overall, most G20 governments were cautious as to how much of their stimulus spending was allocated to low-carbon and other environmental investments during the global crisis.

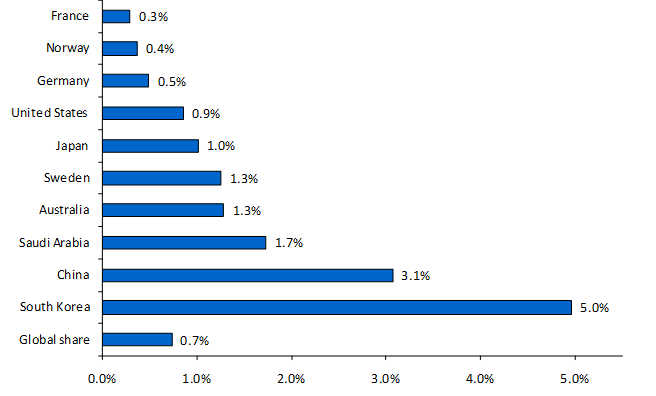

Figure 2. Green stimulus as a share of total fiscal stimulus, from September 2008 through December 2009

Source: Barbier (2010); Robins et al. (2009); Robins et al. (2010).

Figure 3. Green stimulus as a share of GDP, from September 2008 through December 2009

Source: Barbier (2010); Robins et al. (2009); Robins et al. (2010).

Perhaps most revealing, however, was the share of green stimulus measures in GDP, as illustrated in Figure 3. Very few governments spent 1% or more of GDP on green investments during the recession. With the exception of Sweden, all these countries were from the Asia Pacific region. Large-scale green stimulus programs, such as the 5% of GDP planned by South Korea and the 3% of China, were the exception rather than the norm. The US spent 0.9% of GDP on green stimulus, more than the global average, but the EU spent only 0.2% of GDP.

Not green enough

Despite all this, relying on green stimulus alone is simply not enough to instigate a global "green" recovery (Barbier 2009 and 2010a).

Fossil fuel subsidies and other market distortions, as well as the lack of effective environmental pricing policies and regulations, will diminish the impacts of G20 green stimulus investments on long-term investment and job creation in green sectors. Without correcting existing market and policy distortions that underprice the use of natural resources, contribute to environmental degradation and worsen carbon dependency, public investments to stimulate clean energy and other green sectors in the economy will be short lived. The failure to implement and coordinate green stimulus measures across all G20 economies also limits their effectiveness in "greening" the global economy.

Finally, the G20 has devoted less effort to assisting developing economies that have faced worsening poverty and environmental degradation as a result of the global recession. Nor has the G20 taken a leadership role in facilitating negotiations towards a new global climate change agreement to replace the Kyoto Treaty that will expire in 2012.

Urgent: A global green New Deal

Now, more than ever, the world needs a global green New Deal. And it needs the G20 to implement and coordinate this strategy.

There are several reasons why such a worldwide policy initiative is urgent.

- First, the global recession will not diminish the costs of climate change and energy insecurity. The recession was preceded by a surge in global energy prices, with the price of oil reaching $150 a day in July 2008. Due to rising energy costs, prices for food traded internationally increased almost 60% during the first half of 2008, with basic staples such as grains and oilseeds showing the largest increases.

The International Energy Agency (IEA 2008) estimates that, once growth resumes, fossil fuel demand will rise by 45%, and the oil price could reach $180 per barrel. The remaining oil reserves will be concentrated in fewer countries, the risk of oil supply disruptions will rise and oil supply capacity will fall short of demand growth. Greenhouse gas emissions are likely to increase by 45% to 41 gigatonnes in 2030. If atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gasses lead to 5°C to 6°C warming, GDP could fall by 5-10% globally, and by more than 10% in developing economies (Stern 2007).

- Second, the right mix of investments and policies today could not only reduce carbon dependency and improve the environment, but also create jobs and stimulate innovation and growth in key economic sectors.

Certainly, the recovery policies adopted by China and South Korea reflect the belief that investments in clean energy technologies can have a major impact on growth, expanding exports, and creating employment.

For example, one reason that China has adopted green fiscal measures is that its renewable energy sector already has a value of nearly $17 billion and employs close to one million workers. Other green initiatives included promoting fuel-efficient vehicles, rail transport, electricity grid improvements, and pollution control. China has also raised taxes on gasoline and diesel and reduced the sales tax on more fuel-efficient vehicles. In addition, China is the world’s largest recipient of carbon emission reduction credits under the Clean Development Mechanism, currently earning $2 billion from these credits. Overall, China views promotion of green sectors as sound industrial policy: it aims to be the world market leader in solar panels, wind turbines, fuel-efficient cars, and other clean energy industries.

South Korea also sees its industrial strategy tied to green growth. In addition to the green New Deal, the South Korean government plans to establish a $72.2 million renewable energy fund to attract private investment in solar, wind and hydroelectric power projects. In July 2009, South Korea launched a five-year Green Growth Investment Plan, spending an additional $60 billion on reducing carbon dependency and environmental improvements, with the aim of creating up to 1.8 million jobs and boosting economic growth through 2020.

- The most important contribution of a green recovery to the world economy is that it may help alleviate global imbalances (Barbier 2010a and 2010b).

A global green recovery strategy of reducing carbon dependency and improving energy security may help to control both the large current-account deficits incurred by major oil-importing economies, such as the US, or even smaller economies that are facing chronic debt crises, such as Greece, Portugal, and Spain. Globally, such a strategy would also reduce the trade surpluses of fossil fuel exporting economies.

Although the role of any sustained global green recovery in reducing the chronic trade surpluses in Asian and other emerging market economies is more complex, a necessary step will be to rebalance the pattern of economic growth in these economies to absorb more of their savings domestically. Most policy prescriptions advocate moderating the excessive reliance on exports and export-promoting investments, and instead expand imports of capital goods for key sectors with future growth potential and shifting industrial output structure away from labour-intensive goods to skill, capital, and technology-intensive production (Cline 2009; Feldstein 2008; Park and Shin 2009). Such an approach may actually be helped by key elements in a global green recovery strategy (Barbier 2010a and 2010b).

References

Barbier, Edward B (2009), “The G20 agenda should include implementing a global “green” new deal”, Macroeconomics, a Global Crisis Debate, VoxEU.org, March.

Barbier, Edward B (2010a), A Global Green New Deal: Rethinking the Economic Recovery, Cambridge University Press.

Barbier, Edward B (2010b), “Green Stimulus, Green Recovery and Global Imbalances”, World Economics, 11(2):1-27.

Cline, William R (2009), “The Global Financial Crisis and Development Strategy for Emerging Market Economies”, Remarks presented to the Annual Bank Conference on Development Economics, World Bank, Seoul, South Korea, 23 June.

Feldstein, MS (2008), “Resolving the Global Imbalance: The Dollar and the US Saving Rate”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 22(3):113-125

International Energy Agency (2008), World Energy Outlook 2008, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development and the International Energy Agency, Paris.

Park, D and K Shin (2009), “Saving, Investment, and Current Account Surplus in Developing Asia”, ADB Working Paper Series No. 158, Asian Development Bank, Manila, Philippines, April.

Robins, Nick, Robert Clover, and Charanjit Singh (2009), Taking stock of the green stimulus, HSBC Global Research, New York, 23 November.

Robins, Nick, Robert Clover, and D Saravanan (2010), Delivering the green stimulus, HSBC Global Research, New York, 9 March

Stern, Nicholas. 2007. The Economics of Climate Change: The Stern Review. Cambridge University Press.