The Great Recession was characterised by large declines in economic activity in most advanced economies, and in some of those economies the decline has persisted for almost a decade with no sign of the affected economies catching up to long-run trend levels. If anything, the trends are now being revised downward, due to the continuing inability of these economies to close the output gaps first generated in 2008.

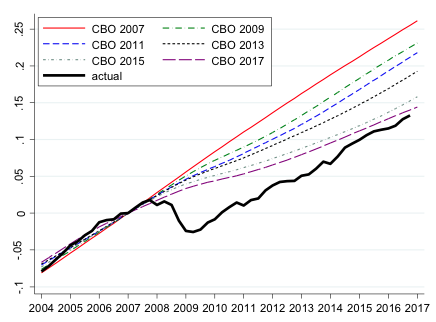

For the US, estimates of potential output have been systematically revised downward since the great recession. Figure 1 shows estimates of US potential output from the Congressional Budget Office. All the current deviations of output from past estimates of potential are now reinterpreted as permanent declines in the productive capacity of the economy. In light of these revisions, some (Summers 2014, 2016, Krugman 2014) have suggested that the US economy has entered a period of secular stagnation. If correct, this interpretation poses seemingly insurmountable challenges for policymakers, given the environment of ultra-low interest rates and limited fiscal capacity to stimulate economic activity.

Figure 1 Historical revisions in CBO estimates of US potential output, and actual GDP

Before we sound the alarm, it is important to understand how estimates of potential output are made, and what determines the revisions of these estimates. In recent research, we have documented how real-time estimates of actual and potential output have responded to economic shocks in the US, and across a range of countries (Coibion et al. 2017).

Institutions do not all estimate potential GDP in the same way. For the US, we consider estimates from the Federal Reserve Board (Fed) and from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). For the cross-section of countries, we look at estimates from the IMF and the OECD. We complemented this with long-term forecasts of output growth

Estimates of potential output respond too much and too slowly

Combining this range of estimates of potential output with a number of different shock measures, we find clear patterns in the data that should make us think twice before we interpret changes in estimates of potential output as indicators of permanent changes in output. Most strikingly, we reproduce the well-documented result that monetary shocks have only transitory effects on GDP. It is startling, though, to see that these shocks are followed by a gradual change in estimates of potential GDP, both in the US and other countries. Government spending shocks have the same pattern: transitory effects on GDP, but estimates of potential GDP again show a delayed response to these shocks, and ultimately respond to the shock in the same direction as the short-run response of GDP. This suggests that estimates of potential GDP fail to distinguish between permanent and transitory shocks. These estimates are sensitive to the cyclical fluctuations in GDP created by demand shocks.

Turning to supply shocks that should affect potential GDP, we again find results that we would not expect from precise estimates of potential output. After productivity shocks that have immediate and persistent effects on GDP, estimates of potential GDP respond only gradually. They take several years to fully incorporate the effects of new productivity levels. Tax shocks create similar results, as estimates of potential GDP catch up to actual changes in GDP only after a long delay. These two supply shocks suggest that estimates will eventually correctly capture changes in potential GDP, but information about these shocks is incorporated into estimates very slowly. There is insufficient cyclical sensitivity of estimates in response to supply shocks.

The role of statistical filters

Statistical and policy organisations that estimate potential output use a variety of methods to do so, including simple statistical filters. Applying a one-sided Hodrick-Prescott filter to real-time US and international data, we can consistently reproduce the way in which estimates of potential GDP respond to shocks. In both US and cross-country data, this approach generates impulse responses to shocks that are nearly indistinguishable from those found using the actual estimates of potential GDP from all organisations, including the counter-cyclical behaviour of potential GDP after oil supply shocks. The HP filter is effectively just a weighted moving-average of recent GDP changes and, by construction, it does not differentiate between the causes (monetary, technology, and so on) of changes in GDP. The widespread use of statistical filters like the HP-filter can therefore explain the gradual response to any economic shock, even those with transitory effects that should be stripped out of estimates of potential GDP.

An alternative approach

We consider an alternative approach, the identification strategy of Blanchard and Quah (1989), which separates supply and demand shocks based on whether they have long-run effects on GDP. This identification restriction, consistent with the empirical results observed in the US and across countries, provides a statistical framework that generates potential output estimates consistent with theoretical predictions.

We applied Blanchard and Quah's approach to real-time data to estimate potential output, defined as the historical contribution of shocks with permanent effects on output. The real-time estimates of potential output using this method react strongly to identified supply shocks, and not significantly to identified demand shocks (monetary policy and government spending shocks). Hence, this new measure of potential output does not suffer from the problems associated with most other measures.

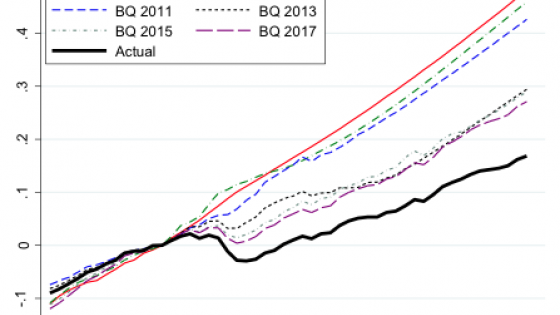

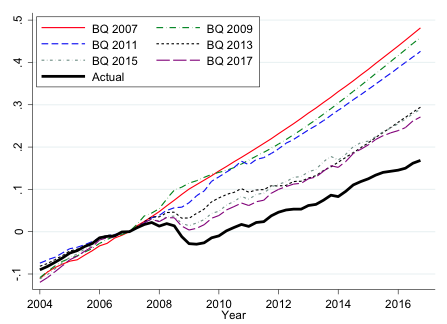

Furthermore, this approach yields a strikingly different interpretation of potential output for the US economy after the great recession. Figure 2 below shows that our estimates imply that US output remains almost 10 percentage points below potential output, leaving plenty of room for policymakers to close the gap using demand-side policies.

Figure 2 Revisions in estimates of US potential output using the Blanchard-Quah (1989) approach, and actual GDP

How should we report changes in potential GDP?

If private and public estimates of potential GDP respond gradually but systematically to every economic shock, and deviate little from what one would expect from simple univariate time series estimates of potential GDP, there are potential policy implications. One is that revisions in estimates of potential GDP currently tell us little about the underlying source of changes in GDP. Also, while revisions in potential GDP are often interpreted as indicating permanent changes in the level of GDP, our results cast doubt on this interpretation. At the moment, even shocks that induce only transitory changes in income cause revisions in estimates of potential GDP. Forecasters attribute much of the decline in output across countries since the great recession to changes in potential GDP, but this tells us little about whether these changes are likely to persist, or can be reversed through monetary or fiscal policies.

There is also much work to be done to create better measures of potential GDP. There are several methods that seem underused. One would be to use additional macroeconomic variables and restrictions to improve the way we identify supply and demand shocks, rather than relying on univariate processes. We could also combine information from public estimates of potential GDP with private sector forecasts, as the private sector seems to have been more successful at isolating supply shocks from demand shocks. Third, we should avoid excessive use of model-averaging, or at least avoid simple approaches like applying HP filters, since these mechanically induce movements in estimates of potential after cyclical demand-driven fluctuations.

More generally, we don't yet have ways to clearly and precisely estimate potential output in real time. This suggests that the practice of relying on the judgement of professional economists should not be discontinued just yet.

References

Blanchard, O and D Quah (1989), 'The Dynamic Effects of Demand and Supply Disturbances', American Economic Review 79(4): 655-673.

Coibion, O, Y Gorodnichenko, and M Ulate (2017), 'The Cyclical Sensitivity in Estimates of Potential Output', NBER Working Paper 23580.

Krugman, P (2014), 'Four observations on secular stagnation', in C Teulings and R Baldwin (eds) Secular Stagnation: Facts, Causes and Cures, CEPR Press.

Summers, L (2016), 'The Age of Secular Stagnation: What It Is and What to Do about It', Foreign Affairs 95(2): 2-9.