What is the problem in Spain? It started with a classic housing bubble financed by foreign capital, and as a textbook would predict, once the inflow of foreign capital stopped and the bubble burst, unemployment soared and the financial system went bust as well (Reinhart 2008).

The current fiscal problems mostly reflect the housing bust. The Spanish government is running a large fiscal deficit as the economy remains weak and the ever-increasing losses in the banking sector hang like a sword of Damocles over the public sector.[1]

On this ground, too much attention has thus been focused recently on the Spanish deficit overshoot in 2011 and what deficit might be attainable in 2012. More attention should be focused on the factors behind the deficit. We argue that the root problem is that the Spanish housing bubble was extreme and that the adjustment has simply been too slow. In particular, we provide a novel angle on two key questions: how long it will take to absorb the legacy of the bubble and how much it will cost?

The Spanish housing bubble

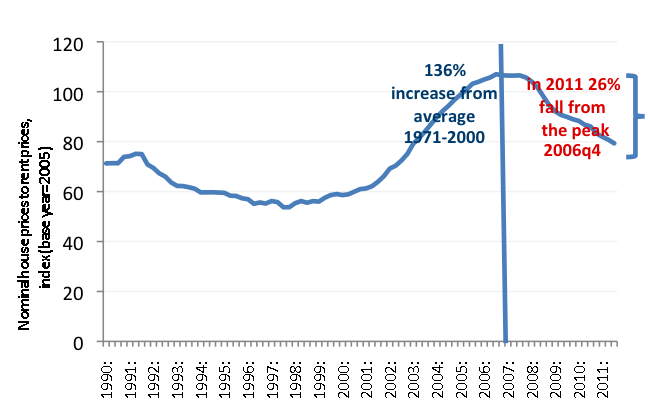

Most commentators concentrate on house prices, usually in real terms, as the measure the housing bubble and its developments (e.g. Münchau 2012). Data suggest that house prices have indeed adjusted, but not enough. Figure 1 shows the house price index for Spain (measured as relative to rents) at roughly the same level as in 2003 and still much above its pre-2000 levels. We favour the price-to-rent index to the real price because it should not be affected by immigration; any increase in demand for housing from that source should manifest itself in upwards pressure on both rents and prices. On the contrary, immigration should put more pressure on rents than on house prices since most immigrants are likely to be short of capital and thus likely to be renting, rather than buying.[2]

The chart confirms that house prices have followed the price-to-rent index since their peak in the last quarter of 2006 but are still higher than the pre-bubble period.

Figure 1. House prices in Spain

Source: OECD

An analogous chart for Ireland would show a full hump-shaped curve, with the current price/rent ratio already back to the level of late 1990s. While Ireland’s price adjustment is close to complete, one could argue that Spain is still only about halfway.

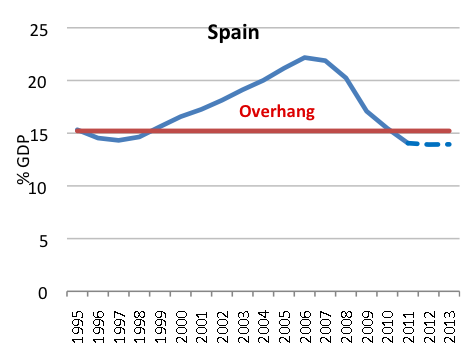

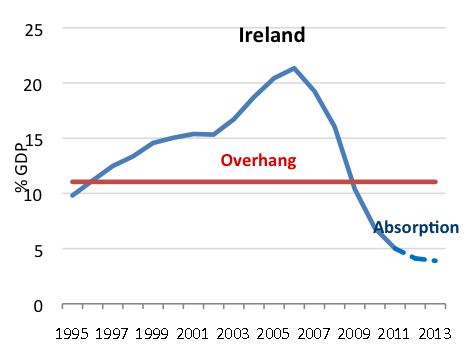

Though this might be true, here we argue that for macroeconomic developments, house prices are less important than the amount of real resources used in the housing sector. What matters for the real economy is the size of the construction sector (especially employment) and its time path relative to the long-run equilibrium. Figure 2 shows spending in construction as a share of GDP for the two countries with the biggest bubbles in Europe: Ireland and Spain.[3]

Figure 2. Housing overhang in Spain and Ireland

Note: Investment in construction as share of GDP on the vertical axis, the red line is the average over the period 1970-2000. Source: European Commission services (Ameco)

The figure can be used to compare the genesis of the housing overhang and its absorption in these two countries. In each chart, the area below the hump curve and above the long-run average of investment in construction (red line) represents our estimate of excess construction and thus our estimate of the overhang (of housing and other fixed structures).[4] For Ireland the cumulated excess of construction between 1997 and 2008 is equivalent to about €99 billion, or 55 % of (2008) GDP. In the case of Spain this is more than €380 billion or 37% of (2010) GDP.

It is often argued that Spain is different because there is a strong demand by foreigners for vacation homes. While this might be true, this is already taken into account in the long run average as shown by an ‘equilibrium’ rate of construction spending (relative to GDP) 5% points higher in Spain than in Ireland and above most European countries.[5]

How far along is the adjustment process?

The area below the red line representing average long-run construction investment measures the process of absorption of the bubble. As houses do not decay rapidly, the only way to bring supply and demand back in balance is by building less.

In both countries, the process is clearly incomplete in the sense that the area measuring the absorption is much smaller than the area measuring the overhang.

- In Ireland, the adjustment has taken place at high speed and about one third of the bubble has already been absorbed.

- In Spain, absorption has hardly started and the forecasts from the EU Commission for 2012 and 2013 (represented by the dotted line) suggest that the adjustment is likely to stagnate.

If construction were to continue at the still relatively high rate of today, the process of absorption of the bubble would take more than 30 years. More recent data, from different sources, on housing starts (and completions) indicate that the Commission forecasts for 2012 and 2013 might understate the fall in the construction activity, which is accelerating again. This might also be the main reason (rather than the fiscal adjustment) why growth rates for Spain are being revised downwards.

The relative good performance of the Spanish economy in 2010–2011 might thus have been due to the fact that during these years the adjustment in both the government accounts and the housing sector slowed down. The long-term costs of this delay are now becoming apparent.

Our very rough estimate of the construction overhang also informs the losses that the banking sector may be facing once adjustment is complete – at least from an order-of-magnitude perspective. In the end, the construction overhang represents the amount of real resources wasted in a sector whose expenditure was financed mostly by credit. It goes without saying that our estimated total of €380 billion exceeds by far the provisions and write downs accumulated by the Spanish banking system (and in particular the savings banks) so far.

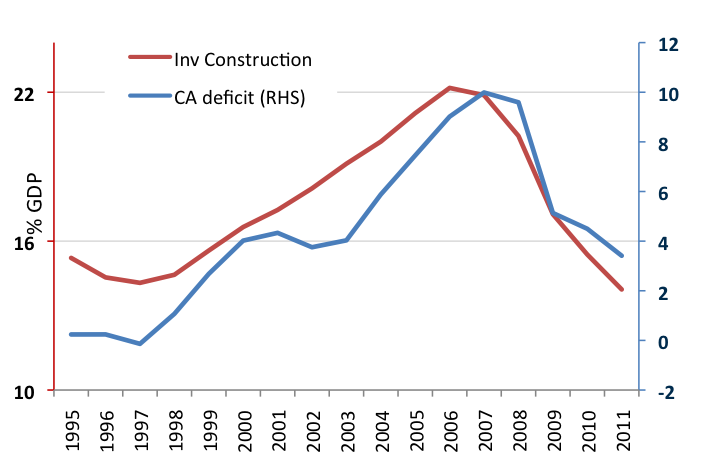

Figure 3. Spain: Construction and current account deficit

The source of funding matters

A housing overhang per se does not have to lead to an acute financial crisis if it was financed by domestic savings (like in Japan and Germany). Unfortunately this as not the case in Spain.

Figure 3 shows that investment expenditure in construction has closely tracked Spain’s accumulation of foreign debt (i.e the current account).

- Over the last decade Spain has accumulated a stock of foreign debt of close to 90% of GDP.

- The Macroeconomic Imbalances Procedure scoreboard of the Commission shows that Spain’s foreign debt already equals Greece’s (EC 2012).

The foreign debt level is rising because the current account is still in deficit. On present trends, it would increase to about 100% of GDP by 2016 (about the level of Portugal today). At this point Spain would clearly be in a danger of being cut off from the market.

What could be done?

Figure 3 shows that the current account adjustment, which was very quick in 2008–2009, slowed considerably when the adjustment in the construction sector slowed as well. The key short-run task for Spain is to stop the accumulation of further foreign debt so that the country no longer depends on continuing inflows of foreign capital. This can be achieved quickly only if the construction sector (which probably wastes further resources) were allowed to shrink further.

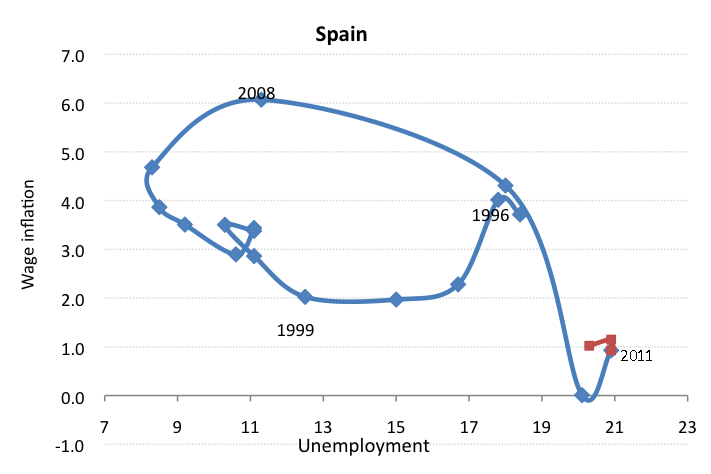

Of course this can work only if the resources liberated by the shrinking construction sector are employed elsewhere in the economy; at this stage the economy can grow only if exports grow as well.[6] This reallocation of labour towards the tradable sector is proceeding only very slowly and will require a fall in wages – at least relative to the rest of the Eurozone, and thus in particular relative to Germany. This requires a labour market in which wages can fall if there is an excess supply. The Spanish record on this account, however, is rather discouraging – as an be seen from the relationship between unemployment and wage growth (the Phillips curve) for Spain shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Spain’s recent Phillips curve

It is apparent that in Spain the Philips curve has deteriorated since 2007 (the rate of wage inflation was much higher in 2008 for the same level of unemployment as during the early 2000s). This is probably due to the backwards wage indexation, which transmits the terms-of-trade shocks from higher oil prices to the labour market. Inspection of this chart seems to suggest that an unemployment rate of over 20% is needed to keep wage inflation close to zero. In Germany, by contrast, wage inflation went to zero at an unemployment rate of about 10%.

Conclusion

All in all, it appears that Spain has not yet fully adjusted to the collapse of its enormous housing bubble, which propelled its economy on an unsustainable path until 2008. House prices have to fall further, the construction sector has to shrink further, and the reallocation of labour towards exportables is slowed down by a labour market that prevents wages from falling quickly enough.

References

European Comission (2012), “Alert Mechanism Report”, February 14.

Gros, Daniel (2007), “Bubbles in real estate? A Longer-Term Comparative Analysis of Housing Prices in Europe and the US”, CEPS Working Document 276, October.

Münchau, Wolfgang (2012), “There is no Spanish siesta for the eurozone”, Financial Times, 18 March.

Reinhart, Carmen M (2008), “Eight hundred years of financial folly”, VoxEU.org, 19 April.

[1] Large fiscal deficits are the consequence of a huge drop in tax revenues after the housing bubble burst and a significant increase in spending for unemployment benefits.

[2] For more details see Annex 2 in Gros (2007).

[3] Here we consider total construction, which includes two main subsectors: dwellings and non-residential and civil engineering constructions. Between 1997 and 2006 the size of the dwelling as share of GDP has almost doubled, going from 6.7% to 12.5%, while the rest of constructions has increased from 7.3% to 9.7%.

[4] Our measure is likely to understate the size of the overhang because during the boom GDP was above its sustainable level as it contained construction and other related activities at an unsustainable pace.

[5] Spain’s long-run average is higher than other European countries’ not only for the overall construction, but also for dwellings.

[6] A recent study by a Spanish bank "Leaving stereotypes behind: Spain recovers competitiveness and productivity faster than any other eurozone economy” (BBVA Economic Watch 2012) shows that exports are indeed growing, but not fast enough to keep unemployment from rising.