Appreciation of the dollar is often associated with a contraction in lending to emerging markets. This pattern has been attributed to flight to safety (Jiang et al. 2018) and foreign currency borrowing (Bruno and Shin 2014). In our recent research (Niepmann and Schmidt-Eisenlohr 2018), we have uncovered a new and surprising relationship: when the dollar appreciates, it is also associated with a contraction of domestic corporate lending by US banks. Credit conditions in the US are subject to the same forces as in emerging markets.

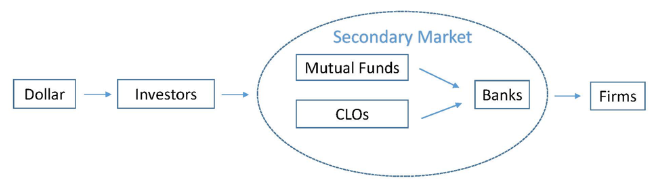

Figure 1 illustrates the mechanism:

- A dollar appreciation is associated with reduced risk appetite among investors with global portfolios.

- These investors lower their demand for collateralised loan obligations (CLOs) and mutual funds that buy syndicated loans, including leveraged loans.

- When these entities buy fewer loans on the secondary market, loan prices fall (especially for risky loans).

- Banks reduce lending to US firms and shift to safer borrowers.

This mechanism is distinct from standard channels through which changes in the US economic outlook and interest rates affect US credit conditions.

Figure 1 How changes in the dollar affect US credit conditions

Source: Niepmann and Schmidt-Eisenlohr (2018).

The role of institutional investors in US corporate lending

Syndicated lending in the US has grown substantially over the last two decades. At the same time, the fundamental structure of this market has changed (Irani et al. 2017). In the 1990s, US banks used to keep most corporate loans on their balance sheets, they now sell around 80% of them on the secondary market within 30 days of origination (Lee et al. 2017).

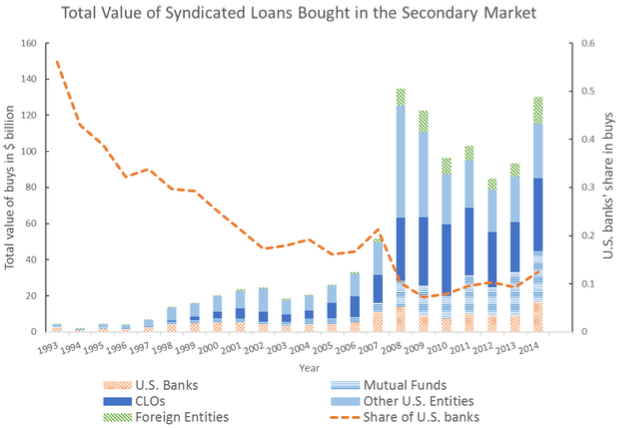

The bars in Figure 2 show the large increase in secondary market sales of US syndicated loans and the composition of buyers derived from Shared National Credit (SNC) data. The increase in sales is striking, but so is a shift in the composition of buyers. In 1993 more than half of the loans were sold to other US banks. This share had declined to less than 15% by 2014 (the dashed line in Figure 2). Today, the largest buyers of loans on the secondary markets are institutional investors – in particular, CLOs and mutual funds.

Figure 2 Syndicated loan sales and the composition of buyers over time

Source: Irani et al. (2017).

Secondary market demand affects US corporate lending

Developments in the secondary market for corporate loans matter for bank lending decisions. When the demand by institutional investors and, hence, prices in the secondary market fall, US banks tighten credit standards and reduce their lending.

Figure 3 illustrates this relationship, plotting thee-quarter moving averages of the S&P/LSTA US Leveraged Loan 100 Index (the blue dashed line), and the share of senior loan officers in the SLOOS survey (the green solid line) that report easing because of secondary market conditions over time.

The green solid line shows the share of loan officers that reported easing credit standards because of improvements in secondary market conditions (corresponding to higher prices). The two lines track each other, highlighting that bank credit standards respond to secondary market prices. Any factor that moves secondary market prices therefore affects borrowing conditions for US firms. We show in the next step that the dollar is such a factor.

Figure 3 Bank lending standards and secondary market loan prices

Source: Niepmann and Schmidt-Eisenlohr (2018).

When the dollar appreciates, investors demand fewer loans on the secondary market

An appreciation of the dollar is associated with lower prices and reduced liquidity in the secondary market for corporate loans. As our analysis shows, this is because institutional investors reduce their demand for this asset class. The lower demand can be seen in mutual fund flow data, for example.

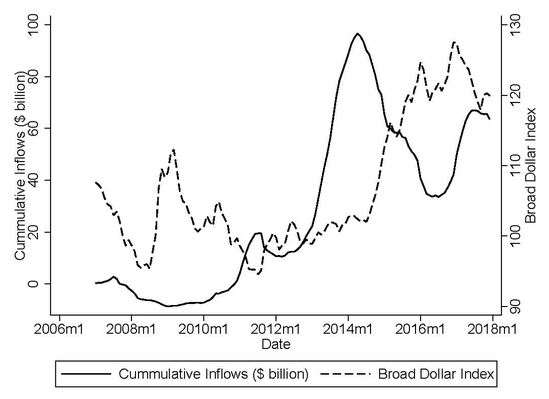

Figure 4 plots cumulative monthly inflows into mutual funds that specialise in US loans from EPFR and the Broad Dollar Index over time. It shows that US mutual funds that specialise in buying US corporate loans (the solid line) experience outflows when the dollar (the dashed line) appreciates.1 Outflows imply that mutual funds have to reduce their holdings of US bank loans. As a result, loan prices fall and banks, in turn, reduce their credit supply, with stronger effects for riskier loans (leveraged loans).

Figure 4 Flows into US bank loan mutual funds and the dollar exchange rate

Source: Niepmann and Schmidt-Eisenlohr (2018).

A stronger dollar implies tighter credit conditions for US firms and higher yields on risky corporate bonds

With the increasing role that institutional investors play as providers of funding for US bank loans, the link between the dollar, loan prices, and bank lending has become stronger over time. The effects are not necessarily confined to those loans that are sold to institutional investors. As banks optimise their balance sheets, they may decide to keep syndicated loans on their balance sheet when investor demand falls and, in turn, reduce other lending – for example, to smaller borrowers.2

We estimate that if the dollar had remained flat from the first quarter of 2014 to the first quarter of 2017, instead of appreciating by around 20%, the largest US banks would have lent an additional $100 billion to US firms. And the association between corporate credit and the dollar is not limited to bank loans. High-yield corporate bond prices also fall when the dollar appreciates, with stronger effects for the riskier bonds. Thus, with the exception of credit for the most highly-rated firms that have access to bond markets, US corporate credit conditions worsen when the dollar appreciates.

Conclusions

Because banks increasingly rely on institutional investors holding global portfolios to buy their loans, US domestic credit conditions have become more dependent on global capital markets –and so exposed to global shocks. While the debate around the Global Financial Cycle (Miranda-Agrippino and Rey 2015, for example) has mainly focused on the effects of US developments on emerging markets, our research suggests that US credit markets may be more exposed to foreign developments than generally understood.

Institutional investors are typically less regulated than banks, and they have more volatile investment strategies. The shift of traditional financial intermediation to capital markets has therefore introduced supply volatility into US credit markets. To promote the stable supply of credit to the US economy and financial stability more broadly, it might not be sufficient to focus on banks. Authorities probably need to take greater account of the role of CLOs, mutual funds and other institutional investors.

Leveraged loan prices fell significantly and high-yield bond issuance dried up at the end of 2018, as global capital markets seem to have less appetite for risk. The first half of 2019 will show how resilient US corporate credit markets are, considering their increased dependence on institutional investors.

References

Avdjiev, S, W Du, C Koch, and H S Shin (2019), “The dollar, bank leverage and the deviation from covered interest parity”, American Economic Review: Insights, forthcoming.

Bruche, M, F Malherbe, and R Meisenzahl (2017), “Pipeline Risk in Leveraged Loan Syndication”, CEPR Discussion Paper 11956.

Bruno, V and H S Shin 2014), “Cross-border banking and global liquidity”, The Review of Economic Studies 82(2): 535-564

Gabaix, X and M Maggiori (2015), “International liquidity and exchange rate dynamics”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 130(3): 1369–1420.

He, Z, B Kelly, and A Manela (2017), “Intermediary asset pricing: New evidence from many asset classes”, Journal of Financial Economics 126(1): 1–35.

Irani, R M, R Iyer, R Meisenzahl, and J-L Peydro (2018), “The Rise of Shadow Banking: Evidence from Capital Regulation”, CEPR Discussion Paper 12913.

Jiang, Z, A Krishnamurthy, and H Lustig (2018), “Foreign Safe Asset Demand and the Dollar Exchange Rate”, NBER working paper 24439.

Lee, S J, L Q Liu, and V Stebunovs (2017), “Risk Taking and Interest Rates: Evidence from Decades in the Global Syndicated Loan Market”, IMF working paper.

Niepmann, F and T Schmidt-Eisenlohr (2018), “Global Investors, the Dollar, and US Credit Conditions”, CEPR Discussion Paper 13237.

Endnotes

[1] More broadly, previous research has found a relationship between risk-taking in global capital markets and the dollar and proposed explanations for the link (Avdjiev et al. 2018, Jiang et al. 2018, Gabbaix and Maggiori 2015, and He et al. 2017).

[2] Bruche et al. (2017) show that banks face 'pipeline risk', the materialisation of which affects credit supply to all firms.