Editors' note: This second column in this two-part series, discussing the impact the Brexit vote has had on the Capital Markets Union, will be published on 18 April.

The financial crisis that hit the euro area a decade ago forced policymakers to take extraordinary steps to preserve the integrity of the monetary union. The launch of Banking Union in 2012 was the most important policy initiative to advance euro area integration since the adoption of the common currency in 1999. The second significant step was the launch of the Capital Markets Union (CMU) project in 2015. Financial union is necessary to complete the EMU architecture and help resume the trend towards financial integration that was abruptly reversed in the aftermath of the crisis.

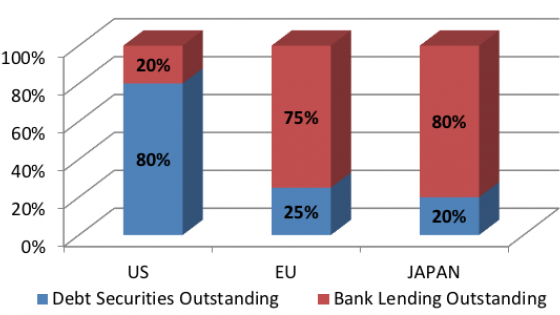

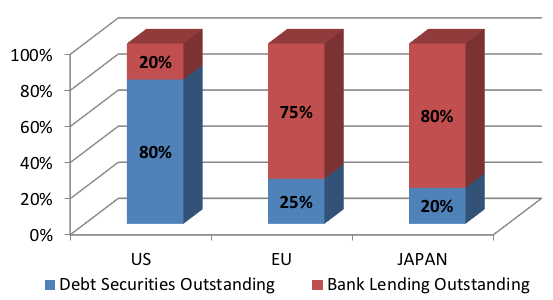

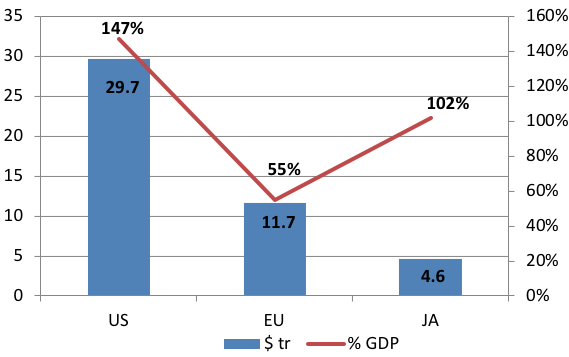

Freedom of capital movements was enshrined in the Treaty of Rome in 1957, but political backing for a road map remained elusive. Impetus for CMU was provided by Europe’s slow recovery from the financial crisis and by the need to identify alternative sources of financing for companies — especially SMEs that make up the bulk of European businesses — at a time when banks were deleveraging. The European Commission laid out its vision for CMU in a Green Paper soon after President Juncker assumed office in November 2014 (European Commission 2015a). The report noted that, compared to the US, European businesses rely much more heavily on banks than on capital markets for funding (Figures 1 and 2). Deeper capital markets would help unlock more funding for investment and attract portfolio investment from the rest of the world. Capital markets also offer an important channel for risk sharing, because the more geographically diversified is a portfolio of financial assets, the less volatile the returns and the less correlated with domestic income. Strong buffers created through private risk sharing were seen as a substitute for public risk sharing (Dijsselbloem 2015). The “Five Presidents’ Report” included Europe’s financial union among the key policy priorities for the future governance of EMU (European Commission 2015b).

Figure 1 Corporate debt financing, 2016 (%)

Data source: SIFMA

Figure 2 Market capitalisation of listed shares, 2016

Data source: Bloomberg and SIFMA

Roadmap

The Green Paper set out the goal of achieving CMU for all 28 EU member states by 2019 to help restart growth and job creation. It proposed to kick-start the process through a €315 billion EU-funded investment package co-financed with the private sector (the ‘Juncker fund’). The EC issued an Action Plan setting out the building blocks of a “well-regulated and fully functioning Capital Markets Union” in the EU by 2019, when a new Parliament and Commission will take office (European Commission 2015c). The proposed reforms are incremental, first tackling the ‘low-hanging fruit’ and gradually building consensus to address more contentious issues in the longer term.

The Brexit vote in mid-2016 was a clear setback, as key elements of the project were delayed to avoid pre-empting the Brexit negotiations. The project’s mid-term review in June 2017 recorded some progress, notably on reviving the market for high-quality securitisations and simplifying prospectus requirements, but other key initiatives were delayed, including harmonising insolvency procedures across EU members. A true CMU requires far-reaching changes in national laws, including harmonisation of accounting and auditing practices, and removal of barriers in areas such as insolvency law, company law, and property rights. EU capital markets remain fragmented as asset managers face barriers in selling their funds across national borders, including diverse tax regimes across jurisdictions and national barriers on clearing, settlement, and custody services. The CMU agenda must ultimately include the transfer of authority over capital markets regulation and supervision to a pan-European authority. Unlike Banking Union, however, this objective was not part of the European Commission’s vision.

Steps taken so far

After a strong start in 2015, implementation of the Action Plan slowed. Two key initiatives – the proposals for “Simple and Transparent Securitizations” and for the simplification of prospectus rules for IPOs and secondary offerings – languished in the European Parliament. The securitisation initiative — one of the flagships of the Action Plan, originally due to be completed in the third quarter of 2015 — was bogged down with complex bargaining over provisions linked to access rights for non-EU members. Agreement on this crucial milestone was finally reached in May 2017 (European Commission 2017a), but it is too soon to tell how STS securitisations, which benefit from lower capital requirements, will work in practice. The STS Regulation and the related Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR) Amendment entered into force on 18 January 2018, but will only take effect on 1 January 2019, after the related secondary legislation is issued, including technical standards and guidelines.

Initiatives relating to the prospectuses for the issuing and offering of securities have also moved forward. A draft regulation that would simplify and standardise the prospectuses was voted into law by the European Parliament in June 2017, and would apply from mid-2019 (European Commission 2017b). The new regulation simplifies the rules and streamlines administrative procedures to make it easier for small businesses to access capital markets. Small issuers (below €8 million) were exempted from the obligation to publish a prospectus.

Although progress has been made, the overall implementation momentum has slowed. The mid-term review of the CMU project in mid-2017 reported progress in completing 20 out of the 33 measures set out in the Action Plan (European Commission 2017c). However, most of these measures were completed past their original deadlines; moreover, ‘completion’ does not imply implementation. While solid groundwork has been completed, in some cases implementation is far from complete and will take time. For example, the initiatives on both STS securitisations and the Prospectus Directive were considered ‘completed’ in 2016, although they will be implemented in 2019. Moreover, some of the Commission’s proposals are not sufficiently ambitious. For example, an EU-wide IPO would still need to be approved by the supervisory authorities of each member state. An IPO by an issuer who wants to be listed on a larger, more liquid market in another member state would still need approval by its home supervisor.

At the mid-term review, the Commission complemented the original Action Plan with nine additional measures. The most important of these was the commitment to strengthen the powers of ESMA to promote the effectiveness and consistency of supervision across the EU, in response to the influx of businesses from London to continental Europe after the Brexit vote (European Commission 2017d). Other new measures were directed at harnessing the transformative power of financial technology and mobilising private capital to fund sustainable investment in green projects, in line with the Paris climate agreement. Proposals were subsequently tabled to promote the growth of crowdfunding platforms and other FinTech initiatives to help match start-up companies and SMEs with savers across the EU (European Commission 2018a). The Commission also set out a road map to channel investments into renewables and energy efficiency (European Commission 2018b).

The mid-term review outlined four legislative initiatives that were subsequently tabled to advance the CMU agenda, which are awaiting approval by the European Parliament and Council:

- A Pan-European Personal Pension Product (PEPP) aims at laying the foundations for a standardised and cost-efficient ‘third pillar’ personal pension scheme that can be managed on a pan-European scale.

- Legal certainty for cross-border securities’ ownership rights: The Commission has tabled proposals to remove the uncertainty surrounding securities ownership in cases when the securities issuer and the investor are located in different EU countries, or when debt claims are used as cross-border collateral.

- EU framework for covered bonds: The aim is to create a more integrated market for covered bonds1 in the EU by setting uniform requirements and strengthening investor protection.

- Capital markets supervision: Strengthening ESMA’s ability to ensure consistent supervision across the EU is essential for the single rulebook to be implemented in a uniform way across the single market. The aim is to apply the same supervisory standard to financial entities with similar business size and risk profiles regardless of where they are located in the EU, thus avoiding regulatory arbitrage.

Conclusion

CMU was motivated by Europe’s slow recovery from the balance sheet recession triggered by the global financial crisis. While CMU was viewed as essential to delivering the Juncker Commission's priority of boosting jobs and growth, this was more of a selling point than any instrument directly targeted at this objective. Stability considerations were not the primary driver, although integrated financial markets were expected to improve Europe’s shock-absorbing capacity through cross-border risk sharing.

The election of pro-reform governments in France and Germany and the rebound in economic activity in Europe are conducive to accelerated implementation of the CMU agenda. However, the incentive to seek alternative funding sources for investment is weakening as bank balance sheets gradually recover. Post-Brexit, the project should focus on achieving CMU among the EU27. Such a project should be viewed as part of a long-term agenda rather than as a short-term expedient to overcome the reluctance of banks to lend and boost investment. Progress toward CMU is possible without impinging on contentious issues involving fiscal backstops. Unlike prudential supervision, which needs to be accompanied by a resolution framework with fiscal implications, enforcement of capital market rules such as those governing authorisation of funds for retail distribution or issuance of securities does not generate fiscal responsibilities.

A successful CMU will emerge through market forces, once regulatory and legal impediments are removed. STS securitisation, streamlining of rules for securities prospectuses, as well as efforts to improve data comparability, increase legal certainty, and harmonise rules for marketing investment products, are all steps in the right direction. At the current pace, however, the building blocks of CMU are unlikely to be in place by 2019. Priority should be placed on deepening financial market integration, as opposed to helping SMEs access market-based finance, tackling investment shortages and promoting infrastructure investment, green bonds or energy-efficient mortgages. These are valid objectives, but they are not central to the CMU project. More effort has to be made in harmonizing insolvency proceedings, improving market infrastructure (‘Giovannini barriers’), developing venture capital and harmonising taxation of financial products. Better harmonized insolvency laws and bankruptcy rules could make it easier for cross-border investors to recoup losses in case a business fails. The World Bank’s Doing Business report for 2018 shows that the recovery rate in insolvency cases ranges from 33.6 cents on the euro in Greece to 88.3 in Finland. The CMU agenda also needs to attract and incorporate more actively household and corporate sector savings in vehicles that will invest in capital markets and encourage them to diversify across the EU, along the lines of the proposed PEPP product. A fragmented financial sector is not only inefficient but also unable to attract investments from overseas.

Author’s note: This column draws on a paper published by CIGI (Xafa 2017).

References

Dijsselbloem, J (2015), Speech by Eurogroup president at the Tatra Summit in Bratislava, 4 November.

European Commission (2015a), “Green Paper: Building a Capital Markets Union”, COM (2015) 63, 18 February.

European Commission (2015b), “The Five Presidents’ Report: Completing Europe’s Economic and Monetary Union”, 22 June.

European Commission (2015c), “Action Plan on Building a Capital Markets Union”, COM (2015) 468, 30 September.

European Commission (2017a) “Capital markets union: agreement reached on securitization”, 30 May.

European Commission (2017b), “Information about Prospectus Regulation (EU) 2017/1129”, press release, June.

European Commission (2017c), “Communication from the Commission on the Mid-Term Review of the Capital Markets Union Action Plan”, COM (2017) 292, 8 June.

European Commission (2017d), “Creating a stronger and more integrated European financial supervision for the Capital Markets Union”, press release, 20 September.

European Commission (2018a), “FinTech: Commission takes action for a more competitive and innovative financial market”, press release, 8 March.

European Commission (2018b), “Sustainable finance: Commission's Action Plan for a greener and cleaner economy”, press release, 8 March.

Xafa, M (2017) “European Capital markets Union Post-Brexit”, CIGI Paper No. 140, August.

Endnotes

[1] Covered bonds are debt securities typically issued by a bank and collateralized against a pool of assets that can cover claims in case the bank fails. Unlike asset-backed securities created in securitization, covered bonds remain on the issuing bank’s balance sheet subject to a capital charge, i.e. they do not create room for new lending.