A growing literature has explored gender differences in making financial decisions. At the same time, there is a parallel literature on the implications of marital status. This research generally reveals a higher degree of risk aversion among women and single people. Studies such as Sundén and Surette (1998), Jianakoplos and Bernasek (1998), and Barber and Odean (2001) consider marital status and gender jointly and conclude that single women exhibit the most cautious attitude.

A common explanation for these findings is that different choices directly reflect innate risk aversion, i.e., an exogenous personal characteristic that exhibits little time variation. With a focus on gender, Crozon and Gneezy (2009) survey the experimental literature and confirm that the stereotype that women are more risk-averse is supported by a robust and significant body of evidence which also points to nature, rather than nurture, as the driving force. But they also notice that gender differences in risk preferences are attenuated, and even disappear, when the subjects of the investigation are appropriately selected; particularly among managers and professional business persons, women no longer behave differently than men. They conclude by suggesting that different subsamples of the workforce may reveal similar patterns.

In a recent paper (Bertocchi et al. 2010), we focus on the impact of marital status on portfolio decisions, investigating the presence, determinants, and evolution of gender differences. In order to address these questions, we have two hypotheses.

Marriage as a risk-free asset

Our first hypothesis is that married women should become less risk-averse because marriage itself can be considered a fairly “safe asset”, especially for women. The idea of marriage as a source of financial security comes from the fact that women tend to have a more insecure societal role. Imagine there are two components of wealth: financial assets and the present value of labour earnings. By getting married, a woman becomes entitled to at least a portion of the gender gap in labour earnings. When no risks are associated with marriage status and the gender earnings gap, or when such risks are uncorrelated with the risks on financial returns, marriage can indeed be viewed as a sort of safe asset that decreases the overall variance of a married woman’s asset position. From this position of relative “safety”, the propensity to invest in risky financial assets should be higher for a married woman. Moreover, the difference between single and married women should be more pronounced than the difference between single and married men, originating a gender gap for the impact of marital status.

Time-invariant marital gap

This leads to our second hypothesis that, because the structure of the family and of the labour market has changed over time, this marital status gap should not be time-invariant. In recent times, the perception of being married as a risk-free status may well have changed in the face of the observed evolution of intra-family dynamics and women’s professional careers. The increasing rates divorce and the decline of marriage have caused a progressive decline of the “traditional family”, while the growing participation of women to the labour market has provoked a parallel reduction of the gender earnings gap.

Yes, married women are less risk-averse…

To explore these hypotheses, we base our analysis on a dataset drawn from the 1989-2006 Bank of Italy Survey of Household Income and Wealth, which supplies information on households’ financial decision makers. Italy provides an ideal setting for our investigation. The last decade has witnessed significant developments in the financial behaviour of Italian households, along both the gender and the marital status dimensions, with a substantial increase of the number of females and singles in charge of financial decisions. Italian society has also experienced a particularly fast and pronounced transformation of its family structure. While divorce became legal only in 1974, divorce figures have boosted in the past ten years. Moreover, the post-war period has witnessed an almost uninterrupted expansion of women’s participation in the labour market.

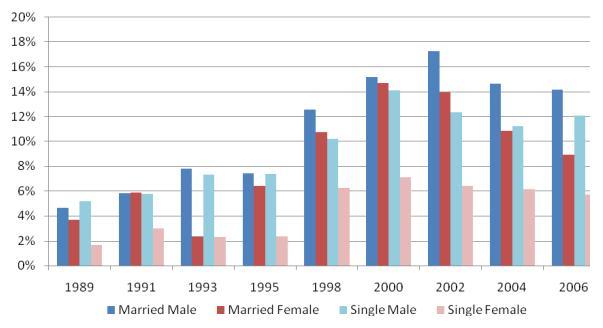

In Figure 1, we document that in 1989-2006 the rate of participation in risky financial assets shows considerable time variation along the gender and the marital status dimensions. Participation increases sensibly, with a peak between 2000 and 2002 as a consequence of the stock market boom. Males generally participate more than females and married participate more than singles. The marital status gap is more marked for women than for men, consistently with our first hypothesis.

Figure 1. Participation rate by gender and marital status, 1989-2006

Note: Percentage of household heads investing in risky financial assets by gender and marital status for each SHIW wave available between 1989 and 2006.

We estimate a probit model for the decision to participate, i.e., the probability to invest in risky assets, separately for males and females. In a basic specification where, beside time and regional dummies, we insert as a regressor a marital status dummy, we find that married household heads are more inclined to invest in risky assets than single ones, and that this marital status gap is larger for women, consistently with our first hypothesis. Including standard explanatory variables reflecting income, wealth, family size, number of children, age, and education, plus a set of interactions between time and marital status, we find that the marital status gap is fully explained for men, but not for women, which reinforces our preliminary conclusion. Moreover, for women – but not for men – we find evidence of a humped-shaped evolution of the marital status gap, with a peak during the intermediate years, which supports our second hypothesis.

…as long as they are not working

But what explains the marital status gender gap? Is it determined by aggregate factors that shape the evolution of gender roles at the societal level? We focus on a subsample of employed household-heads and find that, for women who work, there is no longer any differential behaviour to be attributed to marital status. Any time variability is also gone. Thus, working women align their behaviour to that of men’s, which implies that the humped marital status gap of the full sample has to be attributed to those women who are unemployed or do not belong to the labour force.

Our findings therefore confirm that:

- a gender gap in the valuation of marital status when making portfolio choices, with women valuing marriage more than men;

- an evolution of women’s evaluation of marriage; and

- the absence of all the above for working women. The last finding provides support for the conjecture by Crozon and Gneezy (2009) regarding the potential role of selection through labour markets.

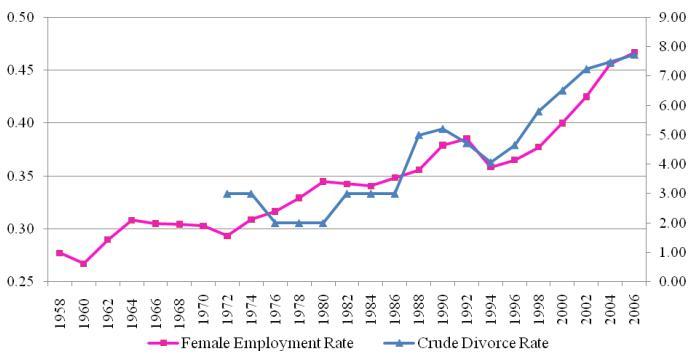

Figure 2. Crude divorce and female employment rates in Italy, 1958-2006

Note: Authors’ elaborations based on data from Istat and OECD. The female employment rate (left scale) is computed as female employment over female working age population (OECD), while the crude divorce rate (right scale) is defined as the number of divorces every 1000 individuals (OECD data up to 1990, Istat thereafter).

We interpret our results as follows. The initial emergence and subsequent decline of the marital status gap for women is the joint product of two forces which are often interconnected (see Stevenson and Wolfers 2007). The first is the increase in labour participation (see Figure 2), which drives a general tendency to the emancipation of all women, even those who are still outside the labour force. Emancipation also involves the ability to make financial decisions, so that we observe an increase of the fraction of married women, including housewives, who take charge. The lagged, cumulative impact of this process can explain the initial expansion of the marital status gap, as it widens the financial participation of women so that, at some point at the beginning of the 1990s, different preferences between married and single emerge.

In those days, married women could still count on a stable position within their marriage, so that their choices differ sharply from those of single women. The marital status gap peaks around 1998-2000. Subsequently, a second force comes into the picture, as documented again in Figure 2. Gradually, the previous decade has shaken the foundations of family structure, with an increase of divorces which has in turn eroded the perception of marriage as a safe asset. It is this devaluation of marriage which, consistent with our hypotheses, can explain the convergence of married women to the same preferences of single women.

References

Barber, Brad M. and Terrence Odean (2001), “Boys will be Boys: Gender, Overconfidence, and Common Stock Investments”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116:261-289.

Bertocchi, Graziella, Marianna Brunetti, and Costanza Torricelli (2010), “Marriage and Other Risky Assets: A Portfolio Approach”, CEPR Discussion Paper 7162, revised, February.

Croson, Rachel and Uri Gneezy (2009), “Gender Differences in Preferences”, Journal of Economic Literature, 47:448–474.

Jianakopolos, Nancy A and Alexandra Bernasek (1998), “Are Women More Risk Averse?”, Economic Inquiry, 36:620-630.

Stevenson, Betsy and Justin Wolfers (2007), “Marriage and Divorce: Changes and Their Driving Forces”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21:27-52.

Sundén, Annika E and Surette, Brian J (1998), “Gender Differences in the Allocation of Assets in Retirement Savings Plans”, American Economic Review, Papers & Proceedings 88:207-211.