Pre-crisis imbalances

The pre-crisis world featured enormous current account imbalances. China’s surplus alone was 0.7% of world GDP in 2008, and the US deficit exceeded 1% of world GDP. At the time, some suggested large imbalances could be sustained for the foreseeable future. Dooley et al. (2003) argued an Asian periphery – primarily China – could pursue a development strategy of export-led growth supported by undervalued exchange rates and capital controls for many years. Moreover, the strategy was a ‘win’ for the US as well, since virtually unlimited demand for its financial assets would have allowed it to run large current account deficits, living beyond its means for years.

The modern mercantilist view, embraced by Aizenman and Lee (2007, 2008) and others, provided a less sanguine interpretation for the persistent global imbalances that emerged in the 2000s. Like earlier mercantilist efforts to expand export markets and accumulate, after the year 2000 countries such as China pushed exports to promote growth, racking up current account surpluses, and growing stockpiles of international reserves. The numbers were impressive. On the eve of the financial crisis, China’s real GDP growth had reached 14% (see Figure 1), its current account surplus had grown to 10% of GDP (Figure 2), and its international reserves had reached almost 45% of GDP, peaking at about 50% in 2010 (Figure 3). However, modern mercantilism could lead to unintended adverse consequences, such as competitive hoarding - a manifestation of growing trade tensions.1

Figure 1 China’s GDP growth rate

Source: Aizenman et al. (2013)

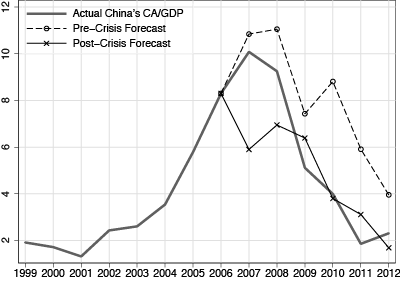

Figure 2 China’s current account/GDP (%)

Source: Aizenman et al. (2013)

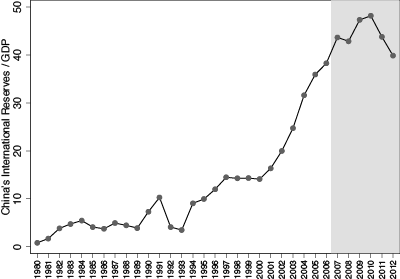

Figure 3 China’s international reserves/GDP (%)

Source: Aizenman et al. (2013)

Imbalances following the crisis

Then, the financial crisis hit. In the US, the private sector was forced to deleverage, and reduced its demand for imports. Other crisis-hit developed countries also cut back on imports. As China experienced weaker export demand, it began promoting greater domestic consumption and investment with the help of a domestic credit boom. It also pursued fiscal stimulus and allowed its real exchange rate to appreciate. It attempted to diversify its holdings of dollar-denominated reserve assets by creating a sovereign wealth fund and encouraging outward foreign direct investment.

Since the onset of the financial crisis, East-West global imbalances have fallen dramatically. China’s current account surplus fell from 10.1% of GDP in 2007, to 2.3% in 2012 (Figure 2). The drop in 2009 alone was the largest ever recorded in the last 30 years. Before the financial crisis, the US current account deficit was about 6% of US GDP in both 2005 and 2006, and 5% in 2007. After the onset of the financial crisis it fell to 2.8% in 2012.

Why current account imbalances fell

Standard macroeconomic models can easily account for the reduction in global imbalances in the immediate aftermath of a financial crisis. Financial frictions and household deleveraging reduce import demand, as well as aggregate demand, in crisis-hit countries, reducing their current account deficits. If weak demand impacts many countries, there are few to take up the slack. Countries with large current account surpluses, such as China, will see demand collapse for their exports, and will experience declining current account surpluses. Policies that stimulate domestic demand to make up for the export shortfall can reduce current account surpluses even more.

In Aizenman et al. (2013), we explore panel regressions as a way to highlight important correlations between current account balances and economic variables, both before and after the financial crisis. The results indicate a structural change post-crisis. The decline in China’s reserve stockpile post-crisis is also shown to be driven by a new wave of outward foreign direct investment into developed economies, as China seeks higher-yielding real foreign assets.2 These developments suggest that China’s smaller current account surpluses and more moderate reserve accumulation may become a longer-term norm, as lower global growth forces China to rely more on domestic demand to expand it economy, and as the high cost of holding international reserves pushes China to place even more emphasis on outward FDI.

Methodology

We assembled panel data on current account balances and other economic variables for a group of developed and developing countries over the period 1980-2012. The estimation draws on the empirical framework in Chinn and Prasad (2003) and Gruber and Kamin (2007). The specification also includes the US demand variable (measured by the US current account deficit as a percentage of GDP) used in Aizenman and Jinjarak (2009) to capture the notion that the US acted as a ‘demander of last resort’ for the exports of China and other countries, enabling them to run big current account surpluses over part of the sample period.

The estimates confirm that a structural change has taken place post-crisis. After the onset of the financial crisis, the US no longer plays such an important role as demander of last resort for the exports of other countries. Its private and public sectors have had to undergo substantial adjustments, making them less able to absorb the world’s exports. The US private sector has had to deleverage in response to the negative wealth effects of declining real estate and portfolio valuations.3 These private and public sector adjustments post-crisis have required the US to retreat from its role as demander of last resort for the world’s exports.

- Prior to the financial crisis, the current accounts of surplus countries are positively and significantly associated with the increase in international reserves, trade, and the increase in the US current account deficit.

- After the financial crisis, the first two correlations are insignificant and the correlation with US demand reverses sign – it is now negative and significant. The role of the US as a demander of last resort is different after 2006.

Figure 4 illustrates China’s current account surplus over the period 1999-2012.4 The pre-crisis forecast predicts a declining current account/GDP surplus for China after 2008. This prediction is in line with the realised decrease in China’s current account surplus, but it under-predicts the magnitude of the decline in each of the post-crisis years. The post-crisis forecast predicts a sharp drop in China’s current account as early as 2007, and over-predicts the decline in China’s current account surplus in both 2007 and 2008. That said, from 2009 onwards, the post-crisis forecast and China’s actual current account match up quite nicely.5

Figure 4 Forecast of China’s current account based on the panel estimation.

Pre-crisis (post-crisis) forecast based on estimated regression coefficients for period 1983-2006 (2007-2012).

Source: Aizenman et al. (2013)

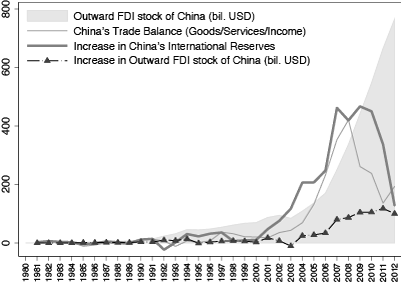

Finally, we examine the changes in China’s international reserves and outwards FDI over the last 33 years (Figure 5). We quantify the sources of these changes. This exercise allows us to trace the changing impact of inward and outward FDI on international reserves, as well as the influence of the trade balance, domestic credit, and real exchange rate appreciation. As there is no reason for the relationship between reserves and these factors to be stable over time, we examine separately the pre-crisis and post-crisis periods.

Figure 5 China’s international reserves and outward FDI

Source: Aizenman et al. (2013)

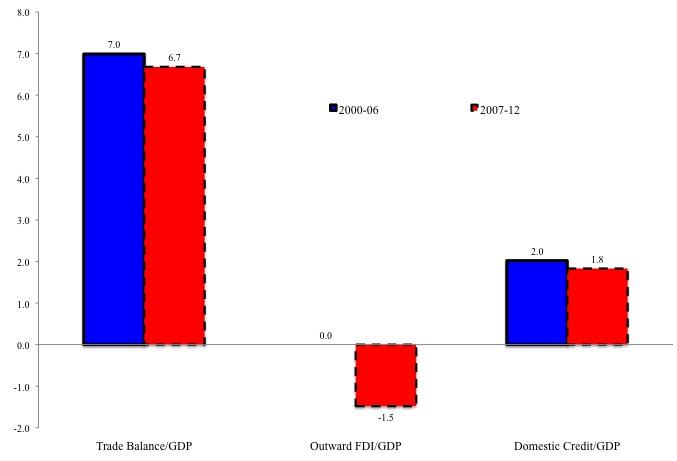

We summarise the sources of changes in China’s international reserves in Figure 6. This figure plots the economic significance of a one standard deviation increase in the source variable on the change in China’s international reserves as a percent of its GDP. The figure reveals the role of China’s trade balance on its international reserves has been remarkably symmetric in the pre- and post-crisis periods, highlighting the common impact of the financial crisis on China’s current account and international reserves. Domestic credit also plays much the same role as a source of change in the pre- and post-crisis periods. The same cannot be said for FDI. Outward FDI played no significant role prior to the crisis but it has become an important source of change in China’s international reserves after the crisis.

Figure 6 Sources of changes in China’s international reserves/GDP (%).

This figure plots economic significance of one-standard-deviation increase in the regressors for China’s international reserves/GDP

Source: Aizenman et al. (2013)

Concluding remarks

To put these results in a broader perspective, it is worth nothing that in 2012, domestic investment in China reached almost 50% of GDP, and domestic credit grew to about 200% of GDP. In addition, China’s saving rate is probably well above the ‘Golden Rule’ rate. These considerations suggest a need to rebalance the economy. China’s remarkable fiscal and monetary stimuli in the early stages of the financial crisis prevented a hard landing during the period 2008-10. However, such policies do not substitute for a needed restructuring of the economy, a restructuring that reverses policies depressing Chinese consumption and preventing faster real appreciation. This rebalancing may entail lower current account surpluses, faster growth of the non-traded sector, and reduced hoarding of reserves. Channeling international reserves into foreign equity and outward FDI may be part of this transformation.

References

Aizenman, J, Y Jinjarak and N Marion (2013), “China's Growth, Stability, and Use of International Reserves”, NBER Working paper No. 19739.

Aizennman, J and F Pasrich (2013), “Why do emerging markets liberalize capital outflow controls? Fiscal versus net capital flows concerns", Journal of International Money and Finance 39(1), pp. 28-64.

Aizenman, J and Y Jinjarak (2009),“The USA as the ‘Demander of Last Resort’ and the Implications for China’s Current Account”, Pacific Economic Review 14(3), pp. 426-442.

Aizenman, J and J Lee (2007), “International Reserves: Precautionary versus Mercantilist Views, Theory and Evidence”, Open Economies Review 18(2), pp. 191-214.

Aizenman, J and J Lee (2008), “Financial versus Monetary Mercantilism -- Long-Run View of large International Reserves Hoarding”, The World Economy 31(5), pp. 593-611.

Chinn, M M and E S Prasad (2003), “Medium-term Determinants of Current Accounts in Industrial and Developing Countries: An Empirical Exploration”, Journal of International Economics 59, pp. 47–76.

Dooley, M, D Folkerts-Landau and P Garber (2003), “An Essay on the Revived Bretton Woods System”, NBER Working Paper No. 9971, published in (2004) as “The Revived Bretton Woods System”, International Journal of Finance and Economics 9, pp. 307-13

Eichengreen, B (2007), Global Imbalances and the Lessons of Bretton Woods, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Feldstein, M (2008), “Resolving the Global Imbalance: The Dollar and the US Saving Rate”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 22(3), pp. 113-25.

Gruber, J W and S B Kamin (2007), “Explaining the Global Pattern of Current Account Imbalances”, Journal of International Money and Finance 26, pp. 500–22.

Obstfeld, M and K Rogoff (2005), “Global Current Account Imbalances and Exchange Rate Adjustments”, Brookings Papers on Economics Activity 1, pp. 67-123.

1 Eichengreen (2007) and Feldstein (2008) argued the Asian periphery was not monolithic; some member of the periphery might abandon fixed exchange rates against the dollar sooner than later, either willingly, or in response to speculative pressures, thereby reducing East-West global imbalances.

2 This new trend is supported by easing capital controls on outward flows. The Wall Street Journal, December 19, 2013 reported from Beijing, “Beijing will ease the approval process for all but the largest Chinese investments in overseas companies and projects, a major relaxation of regulatory oversight that analysts say is aimed at encouraging Chinese firms to expand abroad.” China has joined other emerging markets, easing outflow controls more in response to higher stock price appreciation, higher appreciation pressures in the exchange market and higher real exchange rate volatility (see Aizenman and Pasricha 2013).

3 The more limited access of households to the credit market has raised private savings. The U.S. public sector has contracted in response to the end of the federal fiscal stimulus, the drop of public investment and spending, and the negative stimulus stemming from declining tax revenues and mounting debts in the 50 US states.

4 It also depicts two forecasts of China’s current account for the post-2006 period. The pre-crisis forecast is based on the estimated regression coefficients of the pre-crisis regression, while the post-crisis forecast is based on coefficients from the 2007-12 period regression.

5 The forecast predicts a 1% higher surplus in 2011 than was realized, possibly because it does not account for the fiscal package adopted by China’s government to stimulate the economy.