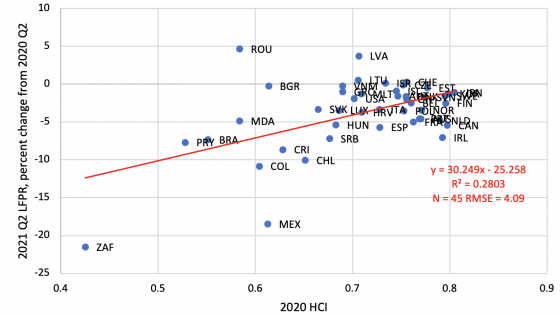

Baldwin and Forslid (2020) posit that labour markets are more robust in nations better endowed with human capital, as high-skill workers are more likely to have flexible work arrangements. High-skill jobs can also be accommodated more easily in a period of social distancing and lockdown measures. If this hypothesis is correct, the recovery in labour force participation in the wake of COVID-19 will be faster in countries with higher human capital. We find that this is indeed the case in a sample of 45 mostly OECD economies during the first year of the pandemic (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Nations with higher human capital recovered faster

Note: The change in the Labour Force Participation Rate is measured between second quarter of 2020 and second quarter of 2021. We use a measure of human capital accumulation as proxy for the share of footloose high-skill jobs in danger of moving to either other countries or being lost to robots. The sample comprises 45 economies with available quarterly data on labour force participation: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Bulgaria, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Korea, Rep., Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Mexico, Moldova, Netherlands, Norway, Paraguay, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Serbia, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United States, and Vietnam.

Source: Authors’ calculations using the Angrist et al. (2021) dataset and the labour force participation rate measured by OECD, last accessed on October 30, 2021.

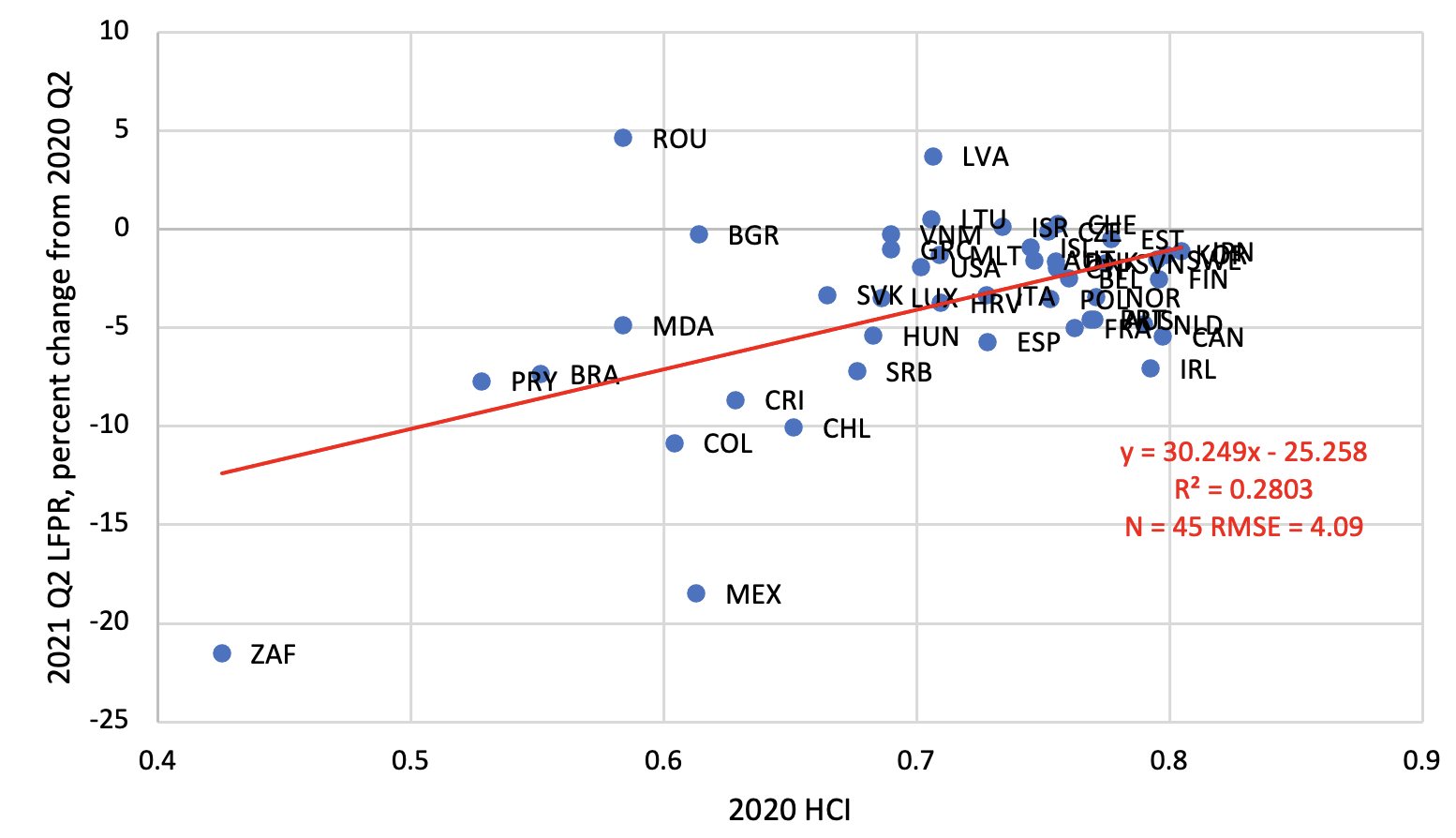

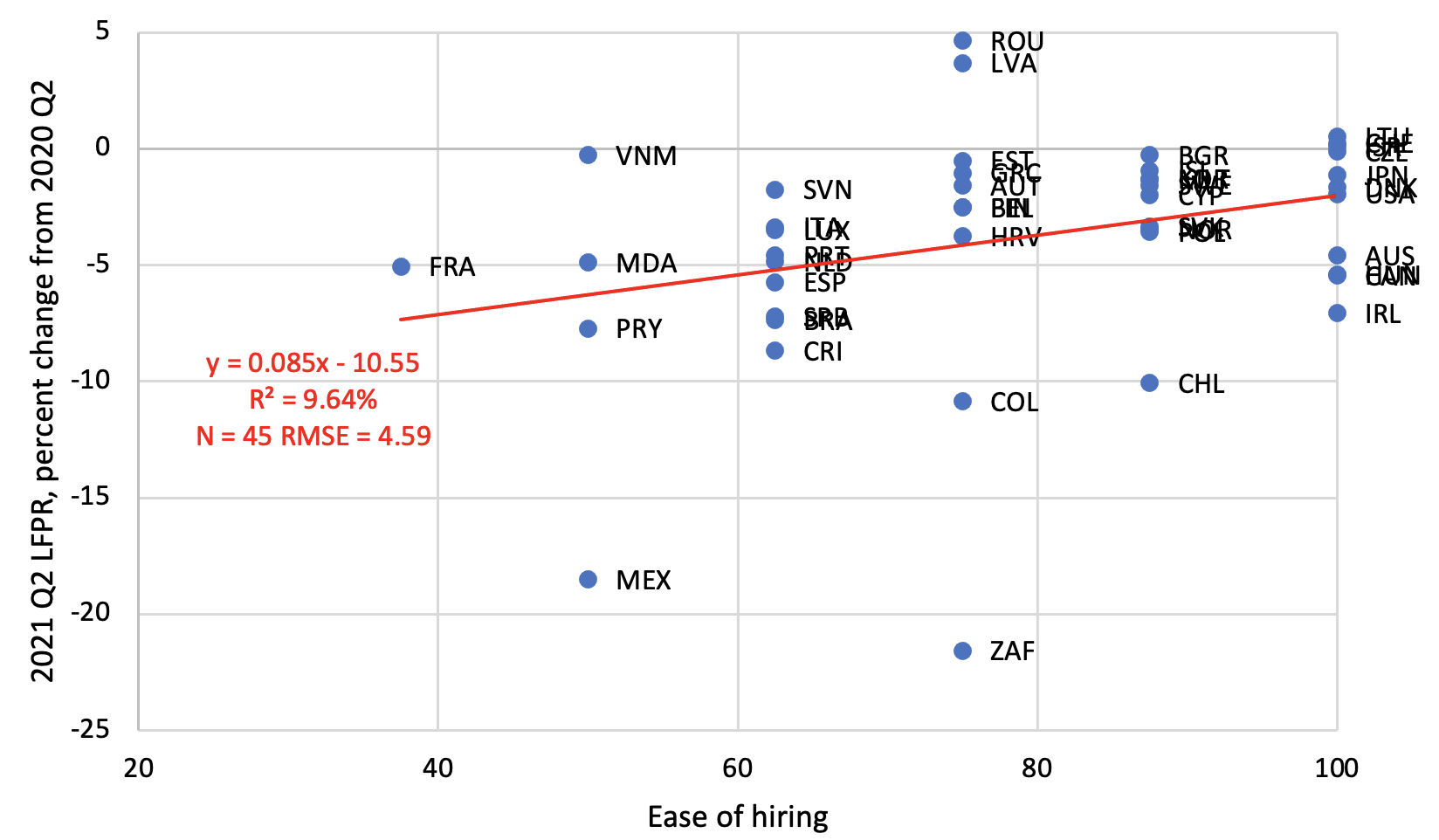

Other, more traditional forces may be at play in the job recovery process too. Since the 1980s, labour regulation has become more flexible in much of the world (Blanchard et al. 2013). The effects of this dynamic have been the subject of much empirical research, particularly in the European context. Bjuggren (2018) finds, for example, that a 2001 reform that increased labour market flexibility in Sweden also improved participation. Bentolila et al. (2012) demonstrate that the wide insider-outsider labour marker divide in southern European economies is reduced with flexible labour rules. Cournede et al. (2016) use OECD data to show that easing employment regulation benefits employment transitions, which in turn increases labour force participation. Botero et al. (2004) use a global dataset to show that flexible labour regulation brings workers to formal jobs, increasing labour force participation.

We find some support for the hypothesis that flexibility in labour market regulation aids the job recovery. In particular, there is a positive correlation between the percentage change in the labour force participation rate in the first year of the pandemic and a regulatory index on the ease of hiring (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Nations with flexible regulation on hiring recovered faster

Note: The change in the Labour Force Participation Rate is measured between second quarter of 2020 and second quarter of 2021. The analysis is performed on the 2019 pre-pandemic data on the ease of hiring, and in particular the availability and maximum length of a fixed-term contracts for permanent tasks. The sample comprises 45 economies with available quarterly data on labour force participation: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Bulgaria, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Korea, Rep., Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Mexico, Moldova, Netherlands, Norway, Paraguay, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Serbia, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United States, and Vietnam.

Source: Authors’ calculations using the updated Botero et al. (2004) dataset and the labour force participation rate measured by OECD, last accessed on October 30, 2021.

We further test the human capital and regulatory flexibility hypotheses using regression analysis. Human capital is positively and statistically significantly correlated with a faster recovery in labour force participation. This is true when controlling for income per capita and ease of hiring regulation. These qualitative results are maintained if we control for other proxies for flexible labour regulation.

The coefficients on labour regulation are positive, though not statistically significant. The interaction terms between regulation and human capital are negative, but also insignificant. Overall, the results show that both high levels of human capital and flexible labour regulation allow labour force participation to recover faster during crisis. The effect of the former is, however, dominant. Irrespective of the level of regulation, countries that prepare to fight the effects of globalization and robotics have also managed to alleviate the effects of the pandemic’s shock on the labour market.

Policy advisors should take note of this result, as it may distort the inference of which labour market policies have yielded positive results during the pandemic. Initial conditions play a significant role in designing such policies, both in terms of regulation as well as – as this column argues – human capital accumulation.

References

Angrist, N, S Djankov, P Goldberg, and H Patrinos (2021), “Measuring human capital using global learning data”, Nature 592: 403–408.

Baldwin, R and R Forslid (2020), “Covid 19, globotics, and development”, VoxEU.org, 16 July.

Bentolila, S, J Dolado, and J Francisco Jimeno (2012), “The Spanish labour market: A very costly insider-outsider divide”, VoxEU.org, 20 January.

Bjuggren, C M (2018), “Employment protection and labor productivity”, Journal of Public Economics 157: 138–57.

Blanchard, O, F Jaumotte, and P Loungani (2013), “Unemployment, labour-market flexibility and IMF advice: Moving beyond mantras”, VoxEU.org,18 October.

Botero, J, S Djankov, R LaPorta, F López-de-Silanes, and A Shleifer (2004), “The regulation of labor”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 119(4): 1339-1382.

Cournède, B, O Denk, and P Garda (2016), “Effects of flexibility-enhancing reforms on employment transitions”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers 1348.