By now, there is a body of evidence demonstrating that racial and ethnic minorities face discrimination in many aspects of life – including labour markets, the criminal justice system, housing markets, consumer markets, even newspaper ratings of professional athletes (e.g. Lang and Kahn-Lang Spitzer 2020, Yinger 1998, van Ours 2021).

A lack of representation in decision-making bodies may increase the likelihood of unequal treatment. This is particularly salient in the criminal justice system, where minority groups tend to be underrepresented amongst jurors or judges while being overrepresented amongst defendants (e.g. Anwar et al. 2012, Anwar et al. 2021, Anwar et al. 2022). Moreover, the consequences of such disparate treatment in the criminal justice system may be especially severe (e.g. Mueller-Smith and Schnepel 2020, Agan et al. forthcoming, Finlay et al. forthcoming) and contribute to the reinforcement and amplification of economic inequalities between minority and majority groups.

For policymakers concerned with addressing unequal treatment in the criminal justice system, a key step is to understand both the extent to which such decision-making biases exist and how they are affected by events that can impact the perceptions of a minority group. The under-representation of minorities amongst judicial decision makers is not a modern-day phenomenon. Historically, minorities were systematically barred from such roles. Did discrimination within the criminal justice system originate with these historical institutions? In a recent paper (Bindler et al. 2023), we study one such historical context – 19th-century jury decisions for Irish defendants and victims – when juries were male, of sufficient wealth, and required to be English-born. This historical context contains potential lessons for today – including the extent to which societal biases are carried over to the courtroom and how biases respond to shocks such as negatively selected immigration waves and terrorist attacks.

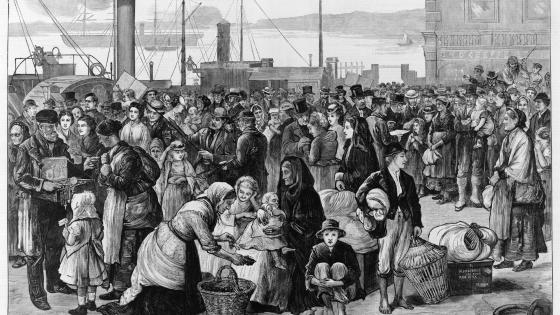

The Irish in 19th-century London

Specifically, we look into the case of the Irish in London during the 19th century, a period of dynamic change. The Irish potato famine (1846–1852) led to a rapid increase in the number of Irish migrants to London (and elsewhere in the country). The Irish became ensconced as an economically disadvantaged group, with gaps in wealth that can be traced to today (Cummins and Ó Gráda 2022a, 2022b). During the second half of the century, political unrest developed with aspirations for an independent Ireland. The campaign for Irish self-government within the British Empire grew and eventually involved a series of bombing attacks by the Irish Republican Brotherhood in the 1880s.

Throughout the century, historical records document open discrimination against the Irish by such means as adding “No Irish Need Apply” to job advertisements. In our paper, we empirically test whether such discrimination carried over to the courtroom. Did jurors treat Irish defendants and victims unequally? The court room setting is interesting for two reasons. First, it allows us to explicitly test (to our knowledge for the first time) for discrimination against the Irish during that period. Second, this is a context in which representation of the Irish as a minority was restricted by legislation. Only males of sufficient wealth who were natural born citizens and residents of England were allowed to serve on a jury. Given the relatively low socioeconomic status of the Irish in London, the wealth requirement added to the birthplace requirement meant that the Irish as a minority group were severely under-represented on juries. Judges were university educated – inequalities in university access at the time thus excluded large shares of the population from this role.

The courtroom data

To study how the Irish were treated by the predominantly English courtroom decision-makers, we analysed data on about 150,000 trials at London’s Old Bailey Central Criminal Court between 1800 and 1899. These are based on a digitised version of The Proceedings of the Old Bailey (Hitchcock et al. 2013), published after each court session and including information about the names of defendants and other courtroom participants, charges, and case outcomes.

The proceedings did not systematically record a defendant’s ethnicity or place of birth. A fundamental step in our research approach was thus to identify Irish and non-Irish courtroom participants. We calculated the probability that each name (surname or first name) in the 1881 Census of England and Wales (Woollaard and Schurer 2000) was Irish, English, or neither, and matched the names (or name variants) of courtroom participants recorded in the proceedings to these ‘odds’. We then classified the names as likely to be Irish, English, or neither, which allowed us to study court outcomes for Irish-named defendants and victims compared to their English-named counterparts.

Disparate treatment of the Irish in the courtroom

Our empirical analyses document significant and robust patterns of unfavourable treatment of Irish-named defendants.

- Throughout the century, Irish-named defendants were treated more harshly by juries: juries were more likely to convict them and less likely to recommend mercy in sentencing.

- These disparities originated in the second quarter of the century and persisted until its end.

- Disparate outcomes were larger for violent offenses, but also seen for property crimes.

- Defendants with more distinct Irish names were treated more harshly.

- The disparate treatment is not explained by other (observable) traits associated with Irish names.

The historical context allows us to study other courtroom parties beyond defendants. Our results are consistent with an under-representation of the Irish minority among decision-makers and with biases of the (England-born) jurors, favouring English-named defendants.

- There is a ‘spillover in animosity’. English defendants were more likely to be convicted when they had Irish versus English co-defendants.

- There is lack of representation. Few jurors had Irish names and many courtroom sessions had no Irish named jurors.

- There is evidence of ‘in-group versus out-group biases’. The gap in conviction rates was driven by cases with Irish defendants and English victims, while conviction rates were somewhat lower for English defendants with Irish victims.

Potential shocks to perceptions

The 19th century was characterised by dynamic change for the Irish in London, including two events that have some similarities to some contemporary global events: the Irish potato famine, which quickly and steeply increased the size of a poor minority population in London, and a series of bombing attacks by the Irish Republican Brotherhood. Did these events negatively affect perceptions of the Irish in London to an extent that carried through to the courtroom?

- Yes for the Irish potato famine, when the gap in conviction rates between Irish and English defendants opened up and grew.

- But not for the period of the bombings, when the gap did not widen further.

Why did these events have contrasting effects? Perceptions in the 1840s and 1880s may have been different to start with – with those in the 1880s having been influenced by the previous decades. Another possibility relates to the nature of the events: The bombings may have seemed less generalisable to the Irish population in London as a whole and easier to attribute to specific individuals who could be held accountable. Finally, the 1880s bombing attacks occurred during a period of ongoing economic assimilation of the Irish in London, which could have had a countervailing impact.

Insights for today?

Our study documents disparate treatment of the Irish, a sizeable migrant group at the time, by the legal system of 19th-century London. While extrapolation from historical to contemporaneous settings always comes with its own challenges, two of our insights may carry over to policy questions today.

First, the disparate treatment of the Irish at court coincides with a lack of representation in the legal system. While we cannot study the counterfactual situation of increased representation in the historical context, our results in combination with contemporaneous empirical evidence on racial disparities and lack of representation in the US context strongly suggest that minority representation matters to building a fair criminal justice system.

Second, the unfavourable treatment at court did not affect only defendants, but also Irish victims. That means that if policymakers strive to design and re-design criminal justice systems and policies in a non-discriminatory way, they will have to take into account not only the treatment of defendants, but of all courtroom participants.

More generally, the unequal treatment of minority defendants and victims by the justice system can have significant adverse effects on families and communities. These adverse effects may not be limited to the current generation, but can persist into future generations via direct intergenerational spillover effects or by contributing to social norms and attitudes towards the minority group. It is thus not implausible that some of the economic inequalities still seen for the Irish in England today originated in 19th-century discrimination against the Irish in the legal system.

References

Agan, A, J Doleac and A Harvey (forthcoming), “Misdemeanor Prosecution”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics.

Anwar, S, P Bayer and R Hjalmarsson (2012), “The Impact of Jury Race in Criminal Trials”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 127(2): 1017–1055.

Anwar, S, P Bayer and R Hjalmarsson (2021), “Unequal Jury Representation and its Consequences”, VoxEU.org, 23 April.

Anwar, S, P Bayer and R Hjalmarsson (2022), “Unequal Jury Representation and Its Consequences”, American Economic Review: Insights 4(2): 159–174.

Bindler, A, R Hjalmarsson, S Machin and M Rubio-Ramos (2023), “Murphy’s Law or Luck of the Irish? Disparate Treatment of the Irish in 19th Century Courts”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 18083.

Cummins, N and C Ó Gráda (2022a), “The Irish in England”, CEPR Discussion Paper DP17439.

Cummins, N and C Ó Gráda (2022b), “The Irish in England”, VoxEU.org, 01 November.

Finley, K, M Mueller-Smith and B Street (forthcoming), “Children’s Exposure to the U.S. Justice System: Evidence from Longitudinal Links between Survey and Administrative Data”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics.

Hitchcock, T, R Shoemaker, C Emsley, S Howard and J McLaughlin et al. (2013), The Old Bailey Proceedings Online, 1674–1913, version 7.1, April.

Lang, K and A Kahn-Lang Spitzer (2020), “Race Discrimination: An Economic Perspective”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 34(2): 68–89.

Mueller-Smith, M and K Schnepel (2020), “Diversion in the Criminal Justice System”, Review of Economic Studies 88(2): 883–936.

Van Ours, J C (2021), “Racial Bias in Newspaper Ratings of Professional Football Players,” VoxEU.org, 22 August.

Woollard, M and K Schurer (2000), “1881 Census for England and Wales, the Channel Islands and the Isle of Man (Enhanced Version)”, Federation of Family History Societies, Genealogical Society of Utah, SN: 4177.

Yinger, J (1998), “Evidence on Discrimination in Consumer Markets”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 12(2): 23–40.