The appeal of pay gap reporting in addressing the gender pay gap is straightforward. Using simple statistics, usually calculated by employers, pay gap reporting offers evidence on the gap between women’s and men’s pay. This gives workers tangible information with which to advocate for fair pay and against discrimination. Relative to other, more costly public policies targeting gender equality, pay transparency rules appear to offer up easy wins.

The recent implementation of the EU Pay Transparency Directive underscores the growing interest in this approach. The Directive gives countries three years to comply with a range of measures, including salary transparency in job advertisements, gender pay gap reporting rules for firms, and a shift in the burden of proof in pay discrimination cases from the employee to the employer.

In June 2022, the OECD conducted an extensive policy questionnaire surveying gender, labour, and social ministries across its 38 member countries. The questionnaire aimed to provide an updated and comprehensive assessment of wage mapping and pay transparency initiatives targeting equal pay, with a specific focus on gender pay gap reporting and equal pay audits. This column explores the findings from the questionnaire, aligns with existing quantitative evidence in this area, and highlights ways in which this information can help inform the implementation, monitoring, and monitoring of pay transparency systems going forward.

Mixed evidence on closing the gender pay gap

National reporting requirements vary in their effectiveness to reduce the gender pay gap, as evidenced by quantitative research.

In quasi-experimental studies of the UK (Blundell 2021, Duchini et al. 2020) and Denmark (Bennedsen et al. 2020), pay gap reporting requirements appear to have led to a narrowing of the gender pay gap in affected firms, likely through a slowdown in the growth of men’s wages. In the UK, transparency has been noted as a contributing factor to closing the wage gap in leadership positions in universities (Bryson and Bachan 2022). Similarly, a more descriptive analysis of the pay reporting system in France suggests the French rules are improving gender equality over time (Briard et al. 2021). In contrast, quasi-experimental studies of Austria and Sweden suggest that pay reporting rules have had little effect on narrowing the wage gap (Böheim and Gust 2021, Swedish National Audit Office 2019).

The fact that national-level pay gap reporting rules do not have a consistently positive effect on narrowing gender pay gaps illustrates the importance of policy design and implementation.

Promising practices and pitfalls

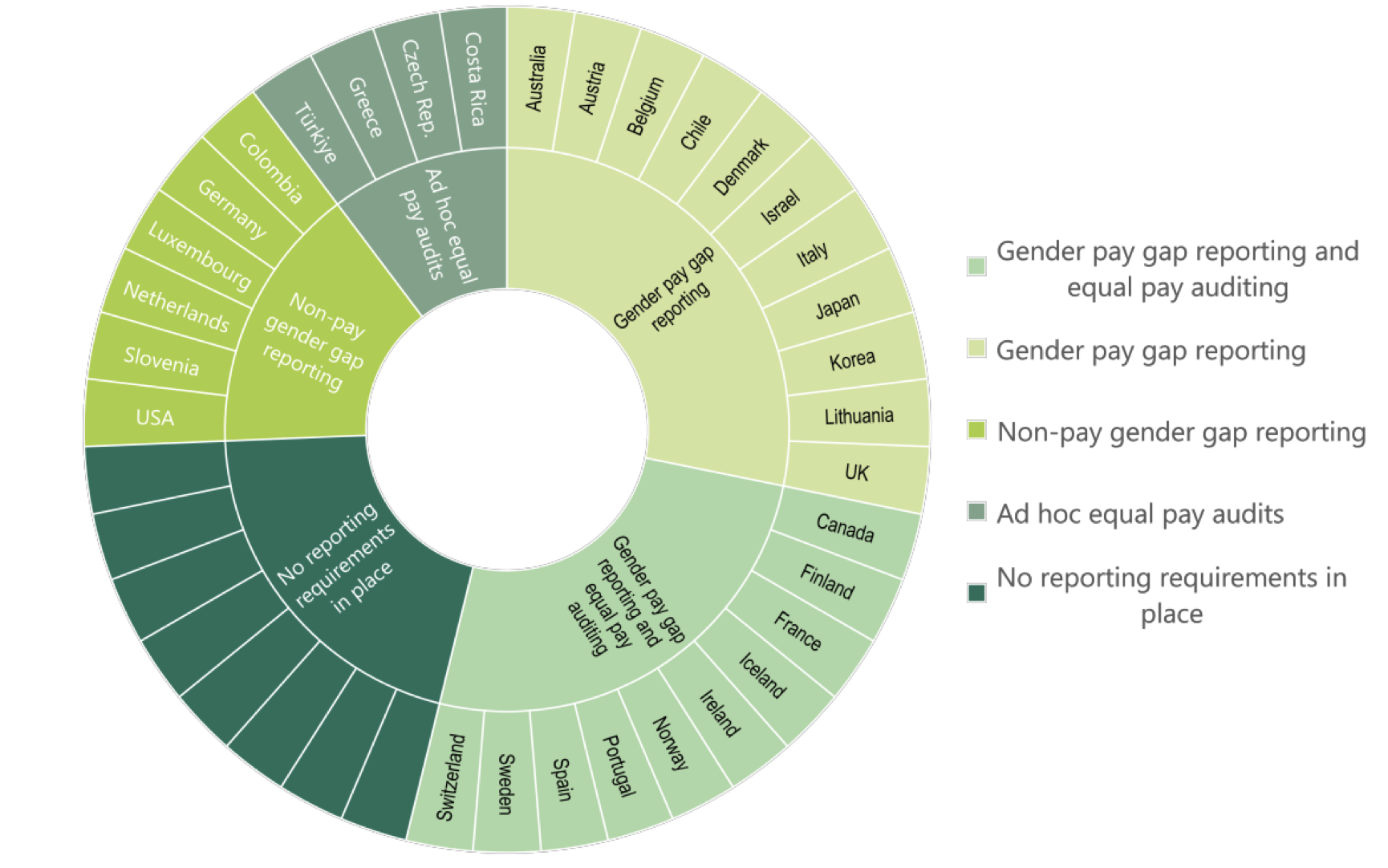

Today just over half of national governments in the OECD (21 of 38) require private sector employers to analyse their pay data and report gender-disaggregated pay information to stakeholders like workers, their representatives, the government, and the public. While pay reporting is increasingly common, no two countries’ pay reporting systems are the same.

Our comprehensive investigation of these 21 national pay gap reporting systems (OECD 2023), combined with the aforementioned quasi-experimental research, offers insights into effective strategies and potential challenges.

Figure 1 Pay transparency measures in place across the OECD

Note: See Figure 1.5 in OECD (2023) for definitions of these groupings. While many OECD countries have subnational pay gap reporting requirements, this study focuses on national-level pay reporting obligations for private sector firms.

Digital tools help firms comply

First, we find digital investments in pay transparency likely pay off in improving employers’ compliance with reporting rules. Governments have been simplifying pay reporting and easing employers’ burden by providing free and accessible calculating/reporting software, as is the case in France, Switzerland (where the introduction of the Logib calculator likely contributed to a smaller gap; see Vaccaro 2017), the UK, and several other countries.

Another particularly novel approach is the use of pre-existing data enabling the government to calculate gender-disaggregated wage statistics for firms. Through semi-structured expert interviews we learned that Lithuania, for example, calculates gender pay gaps for employers using social security contribution data and then reports these gaps on a public website, while Statistics Denmark calculates pay gaps using firm-specific data in its Structure of Earnings Survey and reports these gaps back to firms (OECD 2023).

Of course, these kinds of digital infrastructure may be indicative of a broader public commitment to – and investment in – pay reporting.

Lack of enforcement threatens effectiveness of pay gap reporting regimes

Second, when reviewing countries’ extensive responses to our questionnaire, we were disheartened to learn that very few governments have systematic compliance mechanisms in place to ensure that firms actually report. Sanctions against non-compliant firms are also generally weak. France is arguably the most strongly mobilised on securing compliance: since 2019, the French Labour Inspectorate has carried out over 37 000 interventions and issued 635 formal notices related to its Professional Equality Index (OECD 2023). In the end, however, this resulted in just 42 companies being sanctioned for failing to publish their gender equality score or take adequate corrective measures to address gender gaps – a statistic that has been criticised in the press.

As countries explore regulatory strategies, the role of public ‘naming and shaming’ – or perhaps ‘naming and praising’ – should not be underestimated. Public disclosure of firms’ pay gaps has been cited as critical to ensuring high compliance with reporting rules in the UK (Duchini et al 2020). In the first two years regulations were in effect, the government reported that 100% of firms complied with reporting rules.

Equal pay audit systems hold promise

Third, we found promising practices in equal pay auditing systems, which assess gender pay gaps in more detail, often look at human resources practices related to gender equality, and recommend targeted action to try to address the inequalities that have been found. France and Iceland offer noteworthy examples that merit further evaluation. These systems will likely go further than simple pay gap reporting rules to close gender gaps.

Further evaluations are needed

Combining the quantitative evidence with the results of our policy questionnaire and interviews across countries, improvements in wage gap outcomes appear to be associated with strong third-party involvement in pay reporting. Denmark, for instance, commissions its National Statistics Office to calculate the gap using existing data, while Switzerland provides a free calculator tool and has independent audit requirements. In the UK, reporting gaps to the government and the public implies visibility and informal oversight. And France has an intense pay reporting regime in which the government collects detailed information from firms and monitors compliance.

Critically, more evaluations are needed to understand what works. Only a handful of national regimes – mentioned above – have been analysed quantitatively to assess effects on gender wage gap outcomes. Yet pay gap reporting rules are ripe for quasi-experimental evaluation, with all the usual methodological considerations in mind, as these rules are typically introduced across different thresholds (e.g. firm size) over time. Regular evaluations of programme functioning, including compliance and awareness of rules, are also lacking across countries.

Recognise the limits of pay transparency

Finally – and perhaps most importantly – the big (gender equality) picture matters. Pay transparency can only go so far in promoting gender equality. Too often the onus of identifying, raising, and rectifying pay inequity still rests on individual workers and their representatives – and this is a tremendous burden (OECD 2021). Pay transparency also often comes too late to solve the gender wage gap. It cannot correct choices and constraints accumulated over the life course. It is therefore important to design pay transparency rules in the context of broader, holistic efforts to end gender inequalities in labour markets, society and at home.

References

Bennedsen, M, E Simintzi, M Tsoutsoura and D Wolfenzon (2022), "Do Firms Respond to Gender Pay Gap Transparency?", NBER Working Paper No. 25435.

Blundell, J (2021), "Wage Responses to Gender Pay Gap Reporting Requirements", CEP Discussion Paper 1750.

Böheim, R and S Gust (2021), “The Austrian Pay Transparency Law and the Gender Wage Gap”, IZA Discussion Paper No. 14206.

Briard, K, F Meluzzi and M Ruault (2021), "Index de l’égalité professionnelle : quel bilan depuis son entrée en vigueur?"

Bryson, A and R Bachan (2022), “One high-paid occupation where the gender wage gap has disappeared: Vice Chancellors of the UK’s universities”, VoxEU.org, 15 August.

Duchini, E, S Simion and A Turrell (2020), "Pay transparency and cracks in the glass ceiling".

OECD (2023), Reporting Gender Pay Gaps in OECD Countries: Guidance for Pay Transparency Implementation, Monitoring and Reform, OECD Publishing.

OECD (2022), Report on the implementation of the OECD Gender Recommendations for the Meeting of the Council at Ministerial Level, 9-10 June 2022, OECD Publishing.

OECD (2021), Pay Transparency Tools to Close the Gender Wage Gap, Gender Equality at Work, OECD Publishing.

OECD (2019), Fast Forward to Gender Equality: Mainstreaming, Implementation and Leadership, OECD Publishing.

Swedish National Audit Office (2019), "The Discrimination Act’s equal pay survey requirement – a blunt instrument for reducing the gender pay gap".

Vaccaro, G (2017), "Using econometrics to reduce gender discrimination: Evidence from a difference-in-discontinuity design",

Bennedsen, M, E Simintzi, M Tsoutsoura and D Wolfenzon (2020), “Pay transparency and its effect on the gender pay gap”, VoxEU.org, 7 May.