Several policies around the globe are designed to improve girls’ performance in maths and physics and boost their participation in STEM degrees and careers, including the British Council’s Women in STEM scholarships in the UK, the National Girls Collaborative Project in the US, and the Women in STEM and Entrepreneurship in Australia. The purpose of these programmes is to reduce the gender gap in STEM, which is responsible for a gender pay gap (Card and Payne 2021). What shapes these gender differences in academic outcomes and field of study choices is the focus of recent research (Devereux and Delaney 2019).

Past assumptions suggested that biological factors determine cognitive gender differences in math, while more recent studies emphasise the role of social and psychological factors as drivers of the gender gap in math performance. Research in sociology and psychology supports the notion that teachers treat girls and boys differently overall, and especially in maths instruction. The evidence in economics is limited.

Identifying pro-boy and pro-girl teachers

In a recent paper, we study how teacher gender role attitudes and stereotypes influence the gender gap in STEM by affecting the school environment (Lavy and Megalokonomou 2023). We use administrative data from Greece, where students are randomly exposed to pro-girl or pro-boy teachers in different subjects. This setting offers two unique features: first, students and teachers are quasi-randomly assigned to classrooms within schools; second, students and teachers are followed over time and across grades, giving us panel data information on teachers. Data are also linked to university admissions records for each student.

Our study sample contains more than 400 teachers from 21 high schools over eight years. We first define whether a teacher is pro-boy or pro-girl in a subject in the current class in grade 11. To do this, we use the difference between a blind and a non-blind exam students take in the same grade. The blind is an external exam: the identity of the student, and thus the gender, is hidden and the exam is marked by an external grader. The non-blind is an internal exam in which the identity of the student, and thus the gender, is known to the grader, who is a teacher at the school. Both are high-stakes exams and cover the same material.

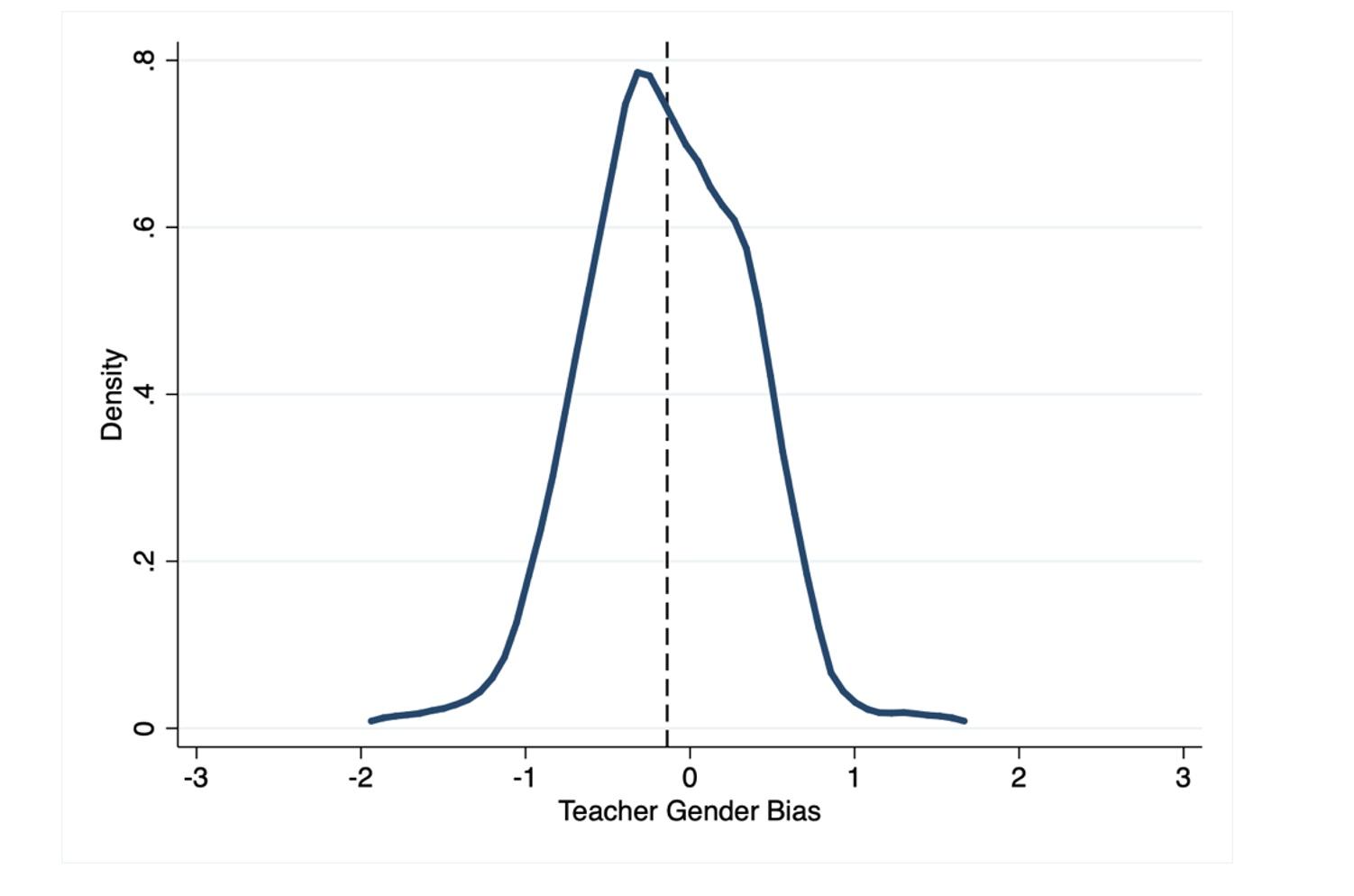

There is substantial variation in teacher gender biases across teachers, as shown in Figure 1. Positive values in the teacher bias measure reveal pro-boy teachers and negative values reveal pro-girl teachers. Gender biases seem to be deeply rooted in teachers’ grading behaviours, since only 15% of teachers are gender-neutral (with a teacher bias very close to zero).

Figure 1 Distribution of teacher gender biases

It is important to note that our bias measure captures grading bias. Since teaching is multidimensional, other aspects of teachers’ instructional styles are likely to be affected by their gendered beliefs and perceptions and have implications for student attainments, motivation, and confidence.

How students are affected, and by how much, depends on which teachers they are assigned. We exploit an institutional setting in which students and teachers are randomly assigned to classrooms (Lavy and Megalokonomou 2023, Dinerstein et al. 2022). In this setting, students are not sorted based on their past behaviour or scholastic achievements. Instead, they are grouped in a random manner and remain with the same group of classmates for most of their high-school classes. Teachers rotate between classrooms to teach classes in subjects of their expertise. Thus, students are assigned to teachers who have different levels of gender-bias across different subjects. For instance, a student may have a pro-girl teacher in history, a pro-boy teacher in physics, and a gender-neutral teacher in chemistry.

There is high persistence in teacher gender biases

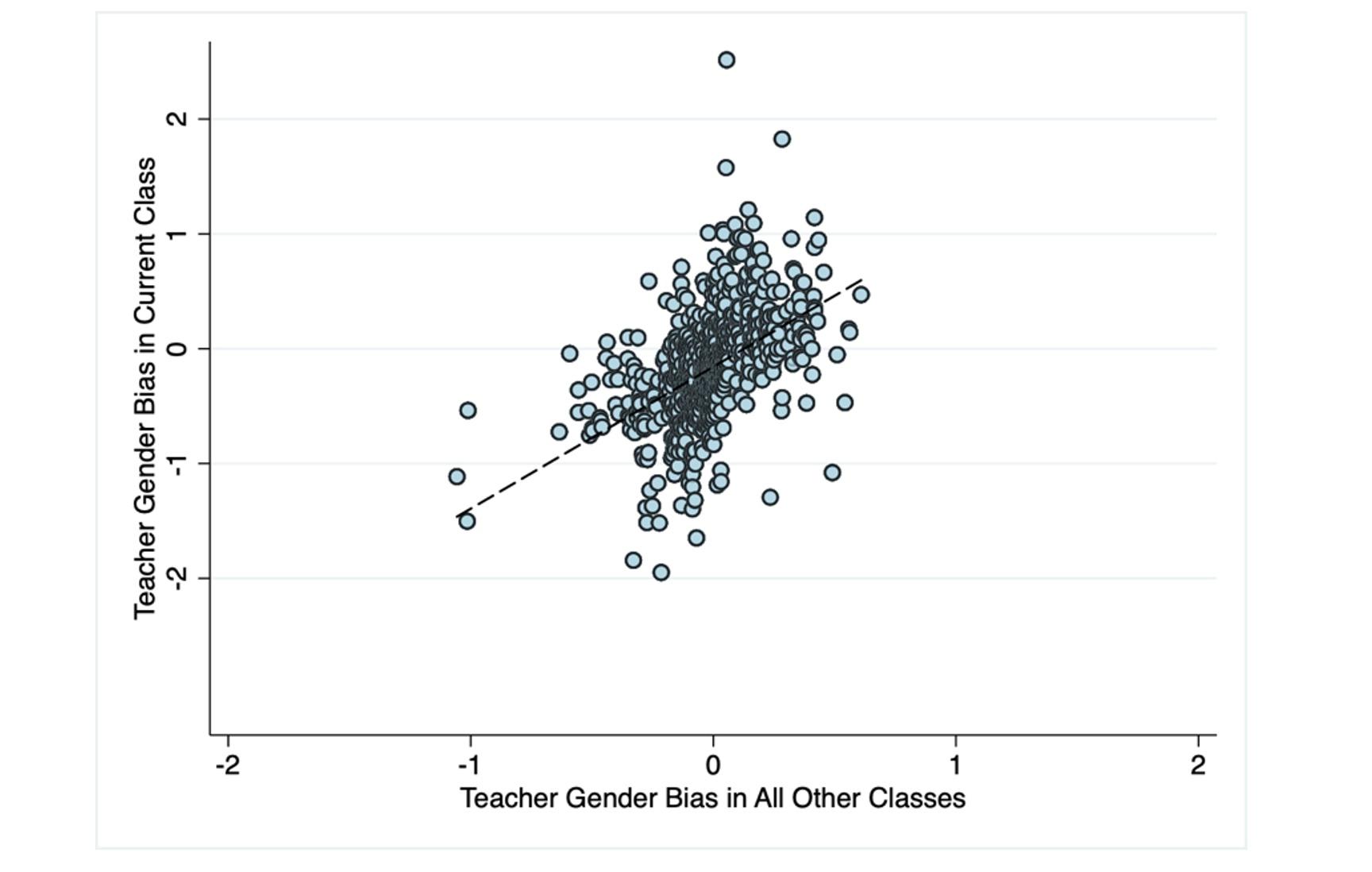

Since we have, on average, observations for each teacher from 16 different classes (and sets of students), we assess the correlation of teachers’ gender biases over time and across classes. To do so, we use ‘out-of-sample’ measures (excluding the current class) of a teacher’s gender bias. This means that we calculate the average bias each teacher exhibits in all other classes they have taught except the current class, and use this as a proxy for their gender bias in the current class. We find a pattern of persistent gender bias among teachers: teachers who show gender-biased behaviour in one class demonstrate the same behaviour in their other classes in the same or other academic years. Figure 2 shows a clustering around the 45-degree line, which indicates high correlation between teacher bias in the current class and teacher bias in all other classes taught by that teacher in the same or other academic years.

Figure 2 Correlation between teacher bias in current class and teacher bias in other classes

Teacher gender biases substantially affect students

Next, we examine the effects of teacher gender biases on student performance in high school and university admissions outcomes. We find substantial effects. Boys randomly assigned to pro-boy teachers in maths or reading in grade 11 perform better in that subject in grade 12. The opposite happens for girls in their maths or reading class: they do significantly worse the next year when they were exposed to a pro-boy teacher in that subject in the previous grade.

We also find that teacher gender biases in early high school have long-term effects on the likelihood of enrolling in a postsecondary institution and the quality of enrolled university degree. The effects are symmetric for boys and girls. Boys who had on average more pro-boy teachers in grade 11 are more likely to enrol in university and for higher quality degrees, and the same is true for girls with more pro-girl teachers. Girls they are less likely to enrol in university and for higher quality degrees when exposed to more pro-boy teachers in grade 11, and the same is true for boys with more pro-girl teachers.

Although the available data limit our ability to decisively understand the mechanisms behind these effects, we find suggestive evidence that teacher biases affect a student’s motivation to attend class. We exploit detailed attendance records and find evidence that students’ unexcused absences changed when assigned to a gender-biased teacher. Boys and girls who are assigned to teachers with biases in favour of (against) their gender reduce (increase) their unexcused absences, while there are no effects on their excused absences. Excused absences are authorised by parents and often require a doctor’s note; unexcused absences capture students’ reluctance to attend class or suspension.

Teacher gender biases have long-term implications for field of study choices

It is not obvious that the short-term effects of teacher gender biases should carry over to long-term impacts on postsecondary choices and attainment, since teachers’ effects on test scores may fade over time (Chetty et al. 2014). Evaluating such long-term effects can help policymakers more accurately assess the potential benefits of training teachers to be aware of unconscious gender biases and correct gendered attitudes and behaviours, given the large impacts these teachers have on students’ lifetime decisions.

We are particularly interested in whether students choose a STEM university degree that leads to a STEM career. STEM degrees are associated with high salaries, innovation, and economic productivity (Peri et al. 2014). In most OECD counties, women are underrepresented in high-paying occupations, and increasing women’s participation in STEM degrees at the university level has triggered widespread discussion of policy (OECD 2023).

We thus ask whether students who were assigned to pro-boy or pro-girl teachers in a specific subject in grade 11 are more or less likely to choose a relevant subject at the university level two to three years later. We find that having a pro-boy or a pro-girl teacher in maths or physics makes no difference for boys, since they are not affected by their teachers’ stereotypic behaviour. But for girls, it does. In particular, having a pro-boy teacher in maths in grade 11 reduces girls’ performance in maths in grade 12 and discourages them from applying for or enrolling in a STEM degree two years later, but having a pro-girl teacher improves their performance and encourages them to pursue a STEM degree. These teachers’ stereotypic biases contribute to the gender gap in academic degrees in STEM fields, and by implication contribute to the gender gap in related occupations as well. These results suggest that teachers’ stereotypic behaviour at important stages in school has long-term implications for occupational choices at adulthood.

Teacher effectiveness is higher for gender-neutral teachers

We next examine whether teachers who discriminate against girls or boys are more likely to be high or low-quality teachers. We find that gender-neutral teachers are higher quality than pro-boy and pro-girl teachers. This suggests that less effective teachers harm their students twice – first by being ineffective, and second by discriminating against one or the other gender.

References

Card, D and A Payne (2021), “High School Choices and the Gender Gap in STEM”, Economic Inquiry 59: 9-28.

Chetty, R, J N Friedman and J E Rockoff (2014), “Measuring the Impacts of Teachers II: Teacher Value-added and Student Outcomes in Adulthood,” American Economic Review 104(9): 2633–79.

Delaney, J M and P J Devereux (2019), “It’s not just for boys! Understanding Gender Differences in STEM”, VoxEU.org, 19 April.

Dinerstein, M, R Megalokonomou and C Yannelis (2022), “Human Capital Depreciation and Returns to Experience”, American Economic Review 112(11): 3725–62.

Lavy, V and R Megalokonomou (2023), “The Short- and the Long-Run Impact of Gender-Biased Teachers”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, forthcoming.

Peri, G, K Shih and C Sparber (2014), “How highly educated immigrants raise native wages”, VoxEU.org, 29 May.

OECD (2023), Joining Forces for Gender Equality: What is Holding us Back?, OECD Publishing.