Since 2014, when Russia annexed Crimea and started the war in Donbas, operational safety has been a crucial element of the business climate in Ukraine. The 2022 full-scale invasion made it even more relevant across the whole country. The stream of investments is walled up by Russian aggression and ongoing war. According to the OECD classification (OECD 2023), Ukraine has the highest possible risk level, on par with Afghanistan, Belarus, Cuba, Iran, Iraq, and several African republics. Reconstruction and recovery needs, as of 24 February 2023, are estimated at $411 billion, covering critical steps to becoming a modern, low-carbon, disaster- and climate-resilient country aligned with EU policies and standards, ready to join the EU (World Bank 2023).

Ukraine, with its proximity to some of the world’s biggest consumer markets, skilled labour, natural resources and well-developed logistical networks, has huge growth potential within a well-established pattern for transition economies joining the EU. Experts argue (Janus 2022, Gorodnichenko et al. 2022) that war-risks insurance would be, therefore, one of the necessary conditions to facilitate investment inflows and let these strengths develop.

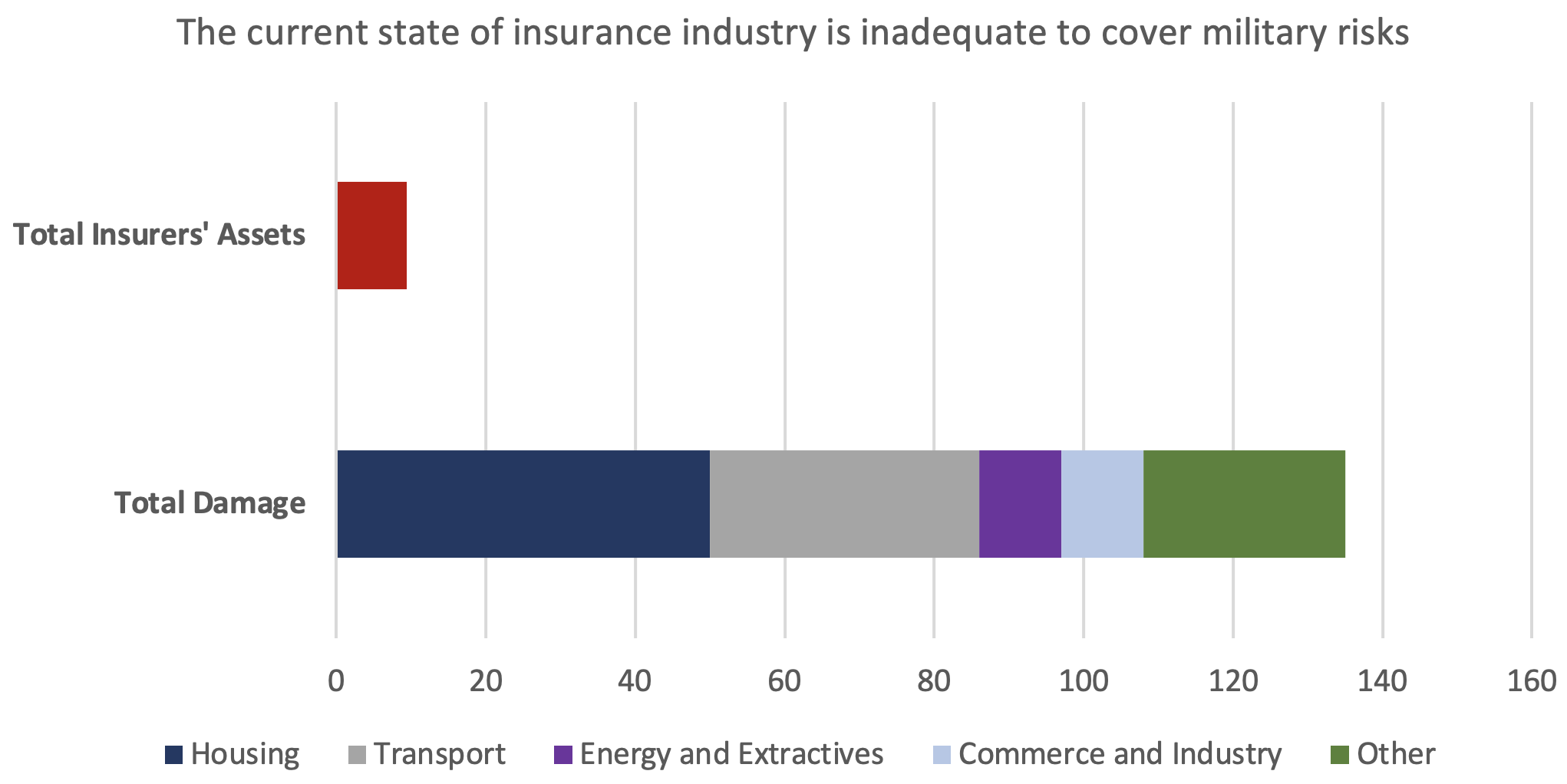

Before 24 February 2022, the Ukrainian insurance market lagged behind its Eastern European counterparts and even the local banking services, with total assets below $2 billion (National Bank of Ukraine 2023). However, insurance and reinsurance coverage for war-related risks were available even in areas near the line of contact in Ukraine’s Donetsk and Lugansk regions, according to several market players. The policies were sold by Ukrainian companies and reinsured on the international markets. Logistics, including marine and aviation, were the most commonly covered packages, but property insurance was also available.

This all changed with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. While there is still a market for some risk coverage like for fire damage, health, or risks in automotive insurance, the insurance coverage of war-related risks became effectively impossible to get in all of Ukraine, with very few exceptions.

Figure 1 Comparison of war-induced damages to insurers’ assets

Notes: Total insurers’ assets are shown for Q4 2022. Damage covers the 12 months from 24 February 2022.

Sources: National Bank of Ukraine, the World Bank.

Currently, there is some international debate focused on a possible solution to this problem. As argued by Alexander Pivovarsky and Ralph De Haas (2023), setting aside a large pool of resources to offer risk insurance via specialised agencies would be critical to mitigate political and war risks. On 21 June 2023, the European Commission, Norway, Switzerland, TaiwanBusiness – EBRD Technical Cooperation Fund, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), and Ukraine signed a statement of intent to cooperate on relaunching the private insurance market in Ukraine, by developing a guarantee facility with key market and public-sector stakeholders (Bennett 2023). While so far only the statement of intention was announced, it nevertheless is an important step to coordinate policies in the future.

Further, the European Commission has proposed a four-year programme of support to Ukraine to set up a new Ukraine Facility as the “Ukraine Guarantee” (European Commission 2023). It is to cover the risks for the following types of operations: (1) loans, including local currency loans; (2) guarantees; (3) counter-guarantees; (4) capital market instruments; and (5) any other form of funding or credit enhancement, insurance, and equity or quasi-equity participations.

Earlier moves from the World Bank’s Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency and the US International Development Finance Corporation, as well as export guarantees from a few governments, are also aimed at insuring against war risks.

But even given all of the above, the organised effort is still in its early stages, and Ukrainian investors are finding themselves in ever more unfair market conditions. Not only do they have much higher borrowing costs compared to European or US companies, but they are also unable to get the risk protection available to foreign investors.

Principles to create an efficient war risks insurance scheme

The following set of principles should help create an efficient war-risks insurance scheme that will enable Ukraine to achieve faster, inclusive, and sustainable economic recovery driven by foreign and local investments (Gorodnichenko and Stepanchuk 2023).

- An international guarantee scheme for war-risks insurance in Ukraine should be governed by a special vehicle with robust corporate governance; funded by international donors as a money pool to carry war-related risks; and implemented by a global reinsurance companies’ consortium to ensure investor confidence. The Israeli approach, where the state covers the damages caused by hostile actions (e.g. terrorism), acts of war by a foreign army, and other damages caused by acts of war by its own Defence Force, is less relevant for Ukraine because of the huge difference in sovereign risk (the credit rating of A+ by Fitch for Israel versus CC for Ukraine). State guarantee from the Ukrainian government would not be enough to gain the trust of foreign investors. Given the incalculable and non-reinsurable nature of the risk, private markets are also not an option. Therefore, the only viable approach would be to seek trustworthy guarantees from third-party entities, such as G7+ governments, to initiate market operations. Such guarantees would also help keep insurance premium rates affordable since, under market terms, the cost of war-related insurance in Ukraine would be prohibitively high for most companies. Additionally, a mechanism for claims against Russia should be established, allowing guarantor countries to recover their funds from the responsible party.

- The insurance should exclusively cover the risks associated with war, such as physical damage to goods and assets, hostile occupation, and contract obligation breaches for war-related reasons, including bank loans, goods, or services supply. It should cover not only total losses of property but also damages of a moderate scale, which is not currently the case (Bennett 2023). Commercial risks, the risk of assets nationalisation and/or capital controls imposition by the Ukrainian state, as well as any risks of sovereign/quasi-sovereigns not honouring financial obligations, should be excluded from this scheme.

- The insurance should be equally accessible to both Ukrainian and international investors, with coverage for all sizes of investments, large and small. While coverage at the initial stages might be prioritised and channelled towards strategic industries, the goal is to open the market to all players, including SMEs, who can purchase insurance policies from their local suppliers.

- The participation of private insurance companies will be necessary. The scheme should not rely on a single state-owned insurance company, as its capacity would be insufficient to cover all the demand, while governance and corruption-related issues might undermine its credibility. Local insurance companies could broker standardised SME deals, while larger international ones could approach large companies and PPP projects on an individual basis. Proper oversight made possible by the pre-war ‘split’ reform, where the National Bank of Ukraine became the insurance market’s supervisor, would be crucial.

- Ukrainian government leadership in the process would be valuable at the conceptual stage, when the eligibility criteria for investors for the insurance and financial service providers for accession to the international guarantee scheme would be determined. The Ukrainian government should also be involved in all the stages of negotiations and scheme design. Supervision over local insurance companies during the implementation stage and ensuring transparency and access to information is also the Ukrainian counterpart’s task. However, the funds and their direct management should be out of the government’s hands to eliminate any possible sovereign-related risks which might affect investors’ trust.

Moving forward

A dedicated and well-coordinated effort is gradually forming to implement a working international mechanism of war-risk insurance for Ukraine’s economic recovery. To succeed, however, work must proceed on three levels. First, international financial institutions and donors must establish a guarantee umbrella, which will be available also for Ukrainian companies. Second, a pool of reinsuring companies and insurance brokers must be created to involve the private sector. And third, a credible and effective mechanism must be established for originating deals in Ukraine that ensure equal access to state and private players, strong market supervision, and an eligibility framework developed aimed at efficient support for Ukraine’s resilience and recovery.

References

Bennett, V (2023), “International move to unlock war insurance for Ukraine investments”, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, 21 June.

European Commission (2023), “Proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on establishing the Ukraine Facility”, COM(2023) 338 final, 20 June.

Gorodnichenko, Y, and S Stepanchuk (eds.) (2023), Ukraine’s road to recovery, Universities UK International.

Gorodnichenko, Y, I Sologoub, and B Weder di Mauro (eds.) (2022), Rebuilding Ukraine: Principles and policies, Paris Report 1, CEPR Press.

Janus, H (2022), “Protection of investments in Ukraine”, Ukrainian economy in war times: Investments desperately seeking cover, Centre for Economic Strategy (Ukraine) Monthly Economic Review.

National Bank of Ukraine (2023), “Non-bank financial sector review, March 2023”.

OECD (2023), “Country risk classifications of the participants to the arrangement on officially supported export credits classification”, 23 June.

Pivovarsky, A, and R De Haas (2023), “The future of finance in post-war Ukraine”, VoxEU.org, 4 January.

World Bank (2023), “Ukraine rapid damage and needs assessment: February 2022 – February 2023”.