The determinants of international flows of talented and highly skilled individuals have attracted attention at least since the Royal Society coined the term ‘brain drain’ to describe the migration of scientists and technologists to North America in the 1950s and early 1960s. These flows have important consequences both for the recipient countries and for those whence the flows originate (Kerr et al. 2016, 2017).

Academic migration is a very large component of these flows and differs in many respects from the movement of other skilled individuals (Parey et al. 2017), such as inventors (Miguelez and Fink 2013) and entrepreneurs (Wahba and Zenou 2012). For example, Yuret (2017) reports that approximately one-third of professors at elite US universities obtained their undergraduate education in a different country. Many countries have similar or higher proportions (for surveys, see Yudkevich 2017, Mihut 2016, and Teichler 2017). Yet sound economic investigations of this topic are scarce. In a recent paper (De Fraja 2023), I contribute to addressing this scarcity with theoretical and empirical analyses of cross-border academic mobility.

The simple and fundamental question I ask in the paper is what induces academics to move from an institution in one country to one in a different country. Individual differences in preferences are clearly important: countries differ in the characteristics of their climate, people, landscape, and built environment, and people differ wildly in their preferred places to live. By the same token, some people prefer to live in the country where they grew up, while others are much keener to roam the world.

Unlike most other potentially internationally mobile individuals, academics are able to engage in short-term cross-border moves. This is because the influence of work location on an academic’s productivity is lower than in most other sectors, as cooperation with colleagues in different countries is just as easy as with co-authors whose office is at the other end of town. This is important for my analysis because it makes academics responsive in principle to short-term exchange rate variations. Someone who intends to move permanently to a given country will be concerned with the purchasing power of their pay in that country, as the overwhelming majority of their expenditures will be made in the currency of the country they live in. But if a person, say, plans to move to country A to start a family in two to three years’ time, they may choose to live and work until then in a country where they can save enough to convert at the expected future exchange rate and purchase the best possible home and other durable goods in country A. Similarly, someone planning to retire in country B in a few years’ time may want to live now in the country where the savings (in real and financial assets) they can accumulate until then will allow them the best possible quality of life in retirement in country B.

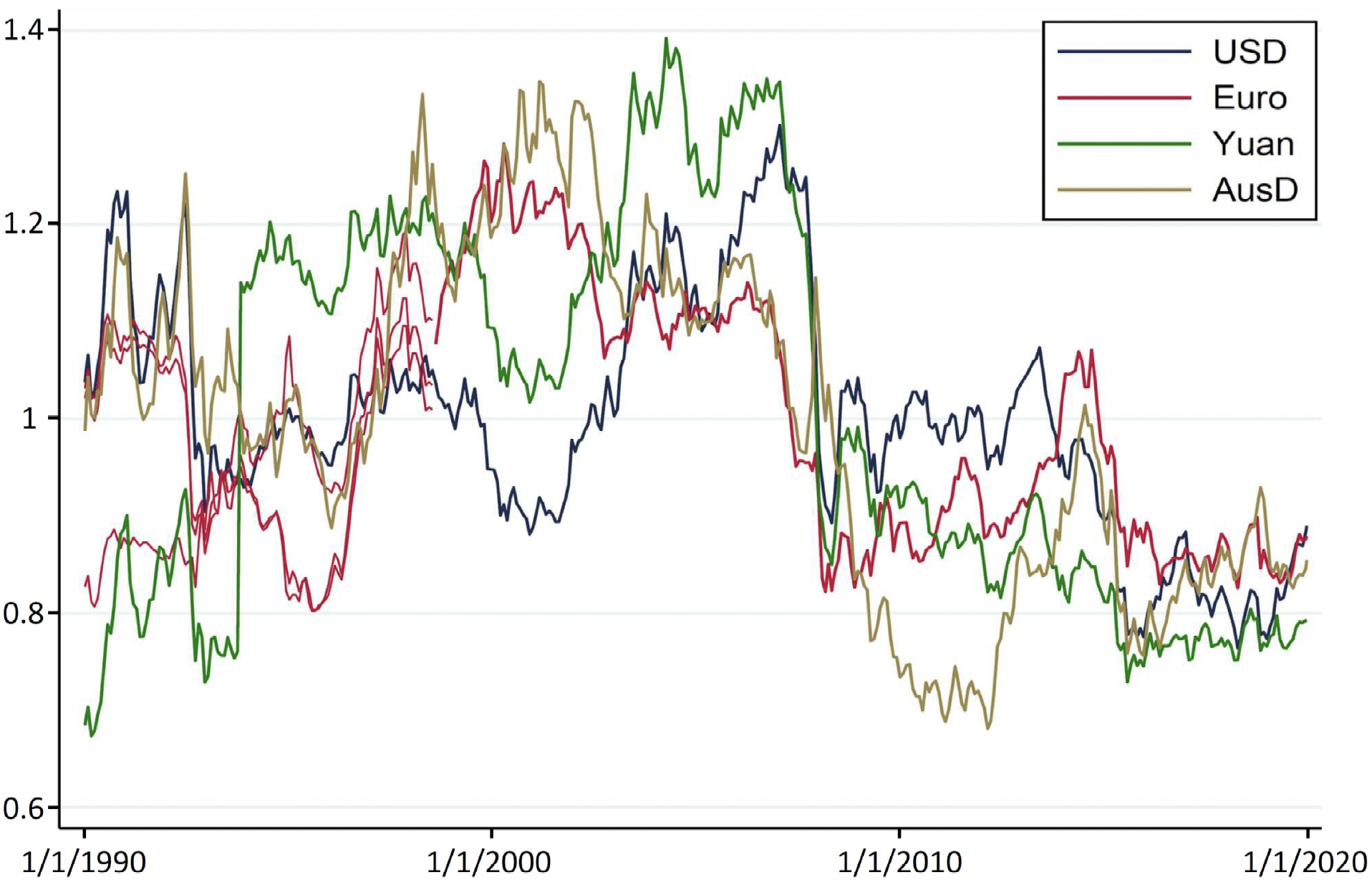

Given this potential influence and the massive extent of exchange rate fluctuations in the period I consider, shown for a selection of currencies in Figure 1, it is essential to include them among the potential determinants of migratory flows. Another category of workers whose choices are affected by exchange rate fluctuations is those who migrate to send remittances to family in their origin country (Nekoei 2013). They, too, care about the purchasing power of their pay in a different currency, and for the same reason as migrating academics: a non-negligible portion of it will be spent after it is converted into a different currency.

Figure 1 Exchange rates fluctuations

Note: Sterling exchange rates 1990-2020, monthly data, for selected currencies. The rates are normalised to 1 on the period average.

The theoretical model in the paper highlights a second reason why exchange rates matter for academics’ location choice, one that does not apply to migrants remitting their pay. While the latter are on fixed (usually low) pay, most academics move as a consequence of successful negotiations with prospective employers. Academics also differ in their bargaining power: clearly, a more successful academic is more attractive to prospective employers, but also more attractive to her current employer, who will therefore be more likely to react to an outside offer with an improved condition in her present post. So it is not obvious whether eminence increases or decreases a person’s likelihood of migration, and to draw the full picture, a formal model becomes necessary. This is based on the two plausible and standard assumptions that academics take into account the effect of today’s choice on future opportunities and aim to maximise lifetime utility, and that both they and their employers can bargain rationally. The results of the model can be summarised thus.

- Academics are, on average, more likely to move to countries where the real exchange rate is higher – that is, countries where their current pay can purchase more units of consumption.

- Academics with more and better publications relative to those of the current members of the institution they negotiate with are more likely to move.

- But academics with more and better publications are less sensitive to exchange rate fluctuations, and can even respond in the opposite way to changes in exchange rates.

- The same is true of older and better-paid academics.

The intuition for the last two points is that more eminent and older academics are less motivated by financial incentives than by prestige and fame. And while an eminent academic can command a higher salary in a negotiation with a foreign institution, the value of this salary decreases as the exchange rate increases.

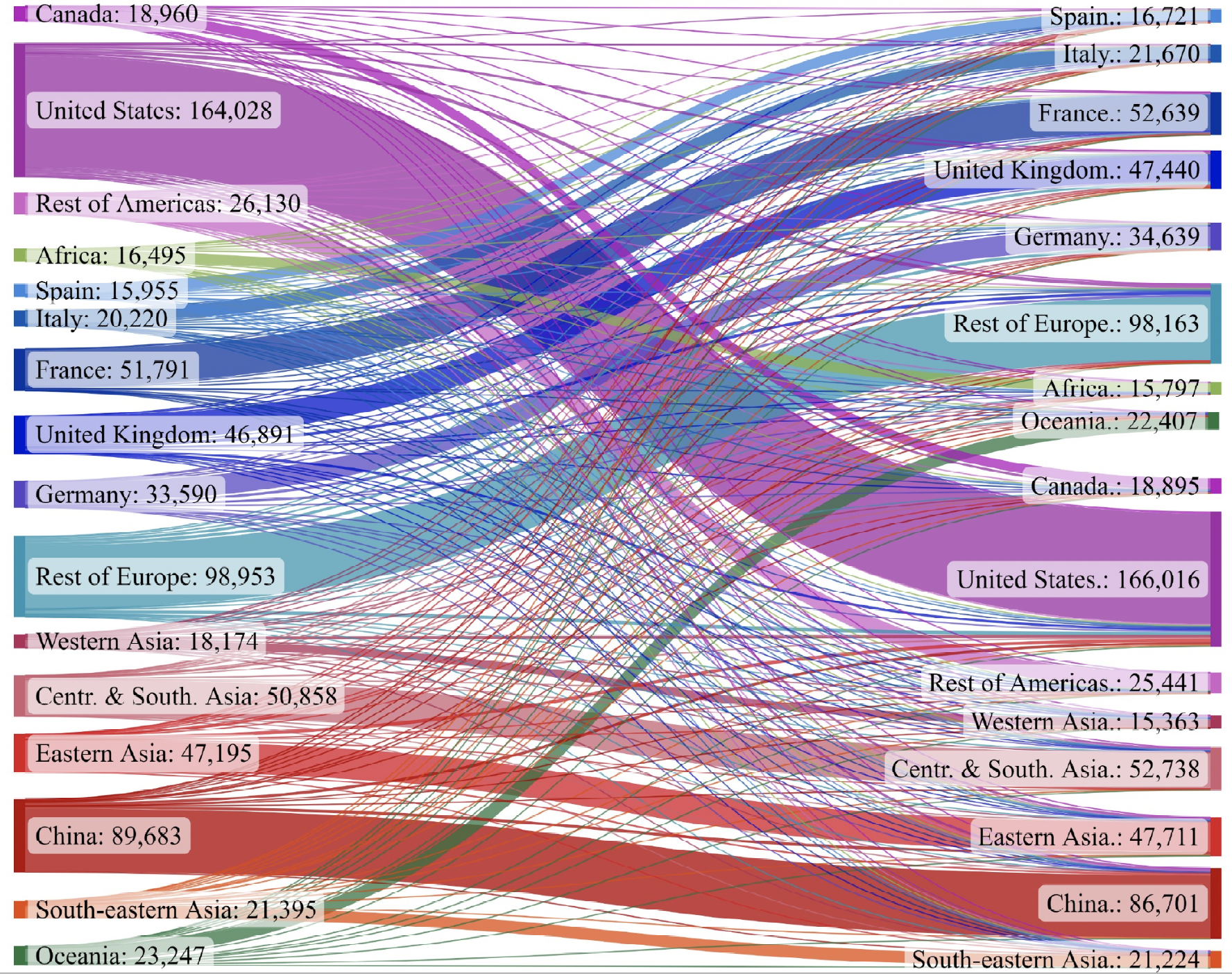

To test the theory, I use public publications records to construct a sample of nearly one million research-active academics working in economics, business, management, statistics, and decision theory over a 33-year period. An academic ‘moves’ when the affiliation indicated in their publications changes from one year to the next. A succinct representation of academic migration for this sample is in Figure 2, which illustrates the movement of academics from one institution to another. The thickness of the flow is proportional to the number of moves from an institution located in a region on the left-hand side to an institution in a region labelled on the right-hand side.

Figure 2 Academic moves

Note: The flows measure academics' moves from one of the regions on the left-hand axis to regions on the right-hand axis. The numbers on the left-hand axies are the number of academics leaving an affiliation in the region, those on the right-hand axis the number of academics moving to an institution in the region.

Note, of course, that some academics will rarely appear in the dataset because they do not publish frequently enough, and so their moves do not register in the data. This implies that I focus on the academics who are more globally visible than those who may instead specialise in necessary and valuable activities such as teaching, or administrative, managerial, and outreach activities. It seems plausible that, precisely because of their more local visibility and their more firm- and country-specific skills, their international mobility is lower and determined more by the mechanisms, personal contacts, head-hunting, and so on that drive other less visible high-skilled workers.

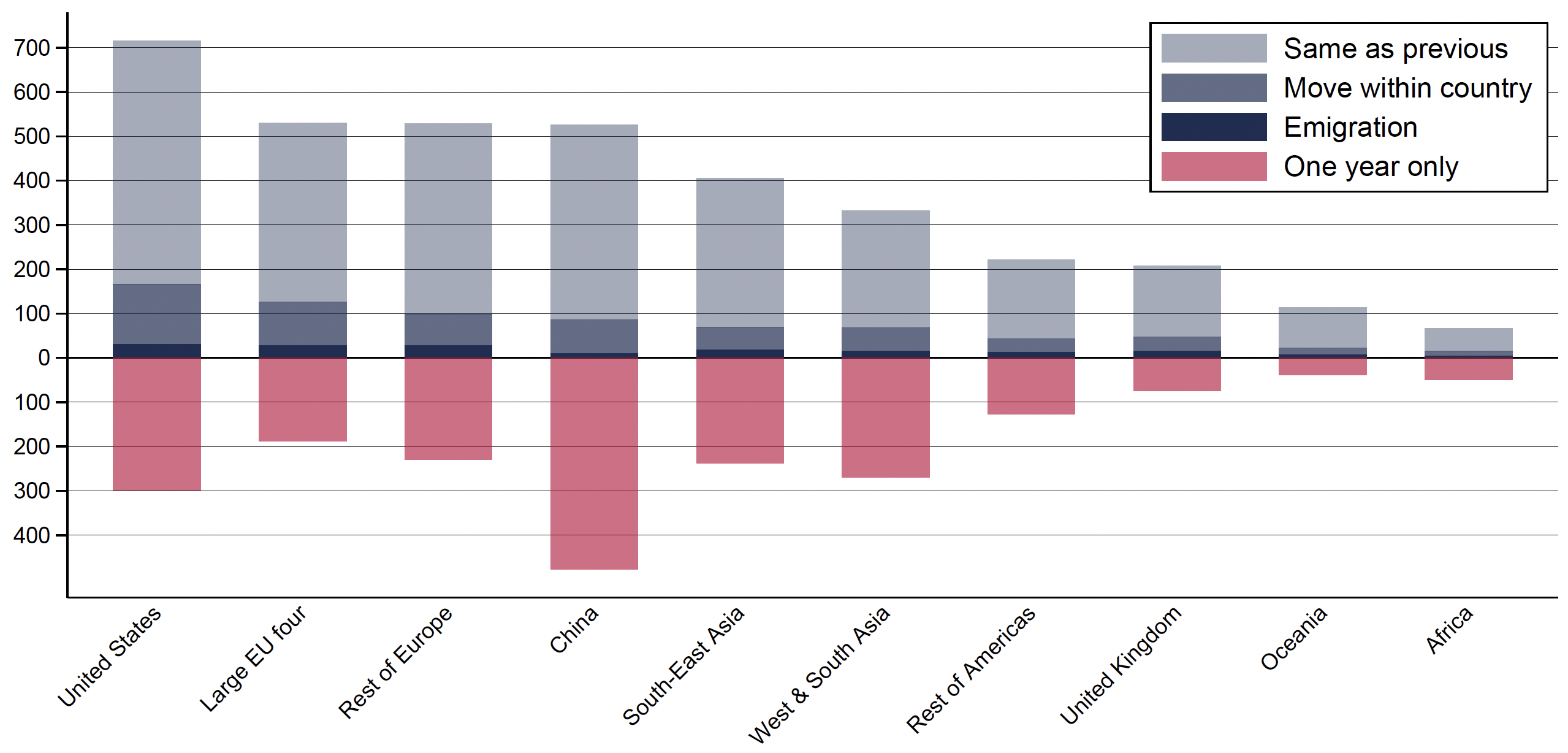

Figure 3 Geographical distribution of academics

Note: The red portion of the bar counts, for each region, the number of academics (in thousands) who make only one appearance in the dataset. Above the horizontal axis, the lighter portion of the bar counts the academics who are always affiliated to the same institution, the darker portion those who move within the same country, and the darkest part those who change country (and hence institution) at least once.

A summary of the geographical distribution of the academics is presented in Figure 3. In each broad region, each academic belongs to one of four groups, defined by the colouring of the bars. The red portion of each bar is the number of academics (in thousand) who make only one appearance in the dataset. Above the horizontal axis, the lighter portion of the bar counts the academics who are always affiliated with the same institution, the darker portion those who move within the same country, and the darkest part those who change country (and hence institution) at least once: in this part of the figure, academics are weighted by the number of appearances in the data.

The first step of the empirical analysis aggregates migratory flows, thus setting aside differences in preferences and eminence among individual academics. It shows that people leave poor countries to move to richer ones (as measured by real GDP per capita), and that the academic prestige of both the origin and the destination country increases the flow of academics between them: countries with more productive academies are more networked, with higher ‘churn’ of academic personnel, suggesting perhaps more flexible matching of research and researchers. I also consider indices of quality of aspects of a country that may matter to academics: perceptions of corruption, the quality of the public administration, and the degree of autonomy enjoyed by universities. The first two may matter as they affect activities such as buying or renting a home, paying taxes, dealing with schools, police, and permits; the last captures the extent of interference from non-academic persons or agencies. Perhaps surprisingly, these do not seem to affect the migratory flows.

The theoretical model, however, predicts that individual preferences are crucial in determining the decision to emigrate and a different statistical approach is required – one that differentiates among individuals, rather than taking their average behaviour. The approach I take in my paper models specific differences in individuals’ emigration propensity between country pairs. This captures the idea that the relative preference for living in, say, Germany or Japan, may vary from individual to individual. The results are in line with the theoretical predictions: more eminent

academics are more likely to emigrate, and an increase in the exchange rate of a country’s currency, which increases the purchasing power of an academic’s current country’s currency, increases that academic’s likelihood of moving to that country. The latter effect is weaker for more eminent academics: in line with the theoretical prediction, they are likely less motivated by financial consideration than by prestige and recognition.

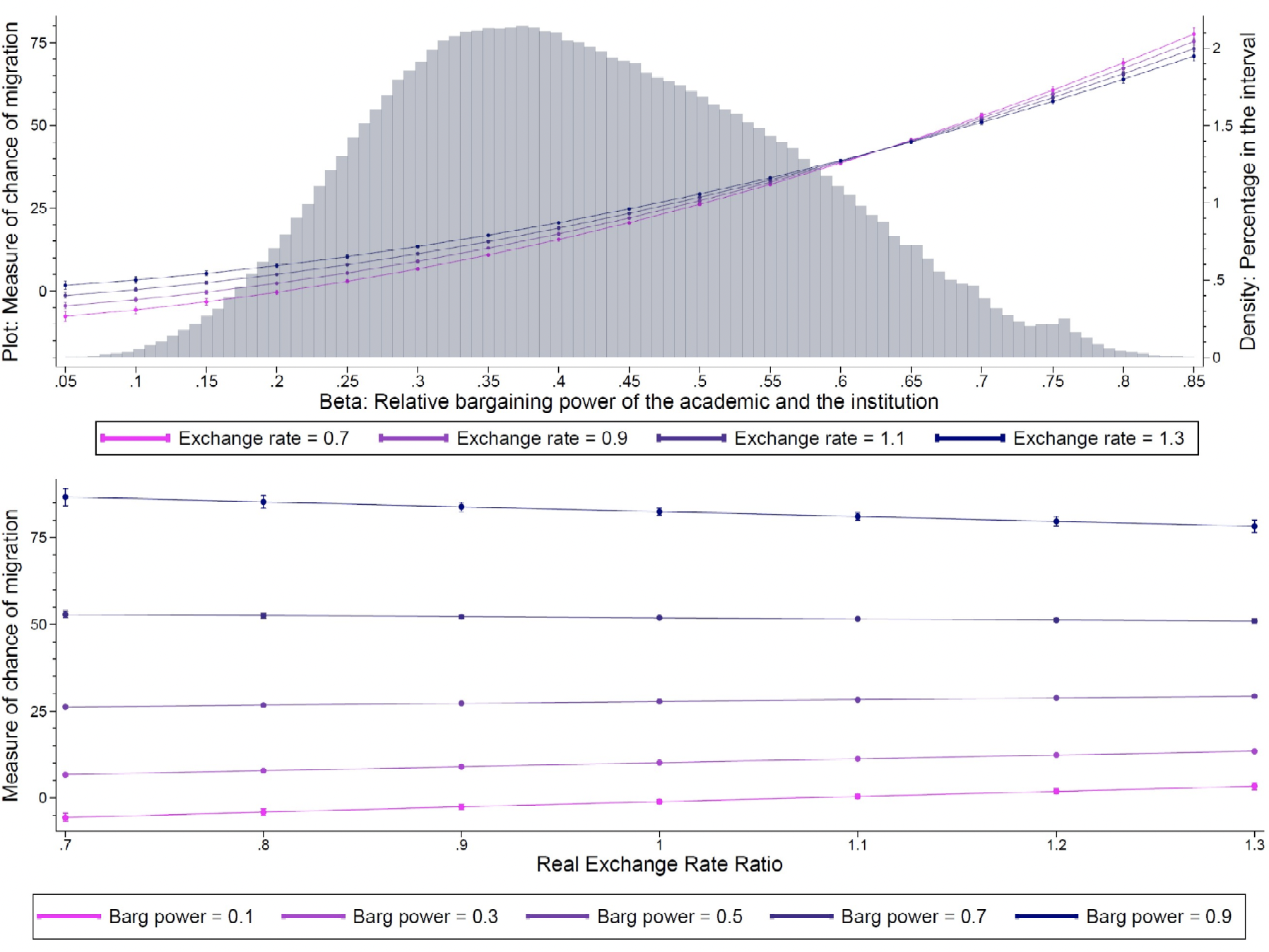

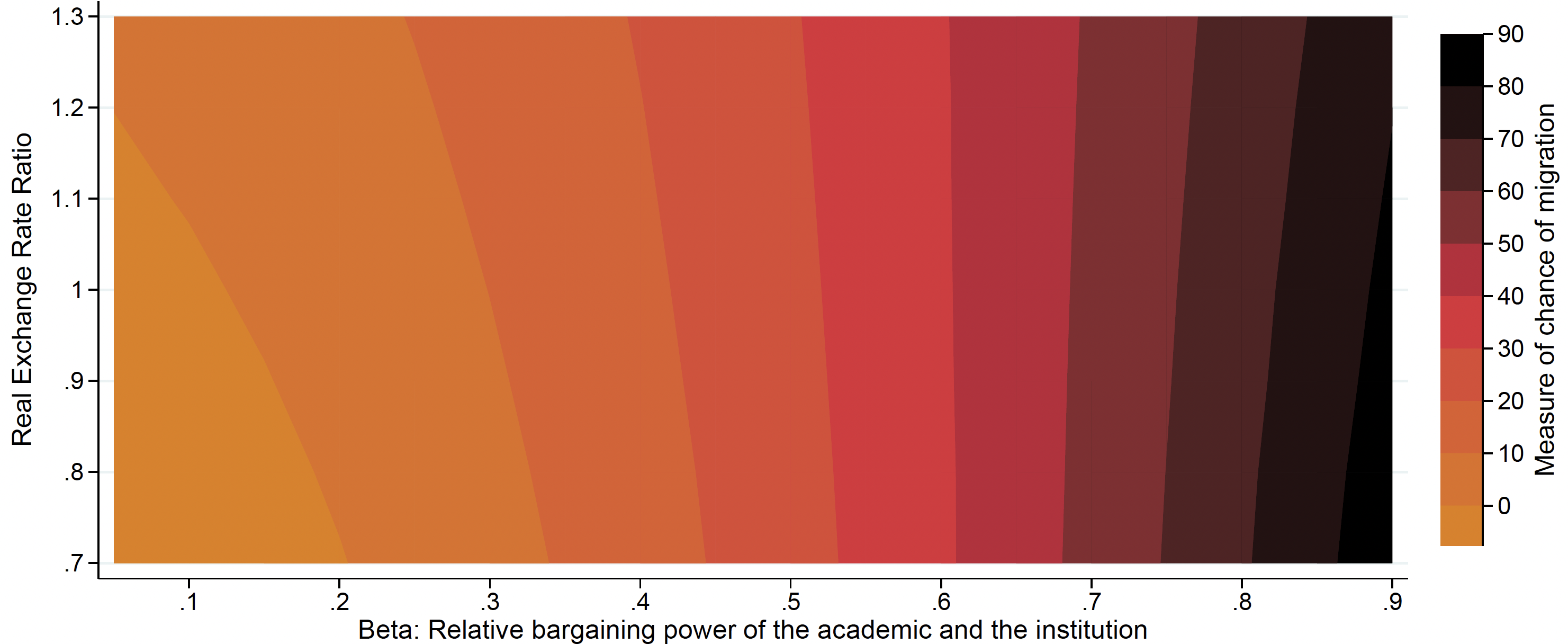

Figure 4 Marginal effects of changes in bargaining power and exchange rate

Note: The top diagram plots the marginal effect of bargaining power at various levels of the exchange rate, overlaid on the density function of the distribution of the academics bargaining power. The lower diagram plots the marginal effect of the exchange rate at various levels of the academic's bargaining power.

Figure 4 is a graphical summary of the results obtained. The horizontal axis measures the relative bargaining power of an academic vis-à-vis the university they are affiliated with in the next year, normalised to be between 0 and 10. The right-hand vertical axis measures the distribution of the bargaining power in the sample studied, given by the grey-shaded area. The four coloured curves plot the predicted probability of migration, measured on the horizontal axis. The curves are increasing, indicating that the probability of migration is higher for academics with more bargaining power. The lower part of the figure shows how the influence of the exchange rate, which is positive on average, is distributed unevenly among academics with different bargaining power. It is strong and positive for individuals with low bargaining power, weaker as the bargaining power increase, and even changes sign for the individuals with the most bargaining power, who are less likely to emigrate as the exchange rate increases. A different viewpoint for the same intuition is given in Figure 5. In a Cartesian plane of the real exchange rate and the bargaining power, the different colours indicate, for academics characterised by a given pair of values of these variables, their predicted probabilities of emigration. Darker shades denote a higher likelihood of migration.

Figure 5 Probability of migration

Note: In the Cartesian plane the colour of each point represents the predicted probability, in percent, that an academic with relative bargaining power measured along the horizontal axis migrates when the exchange rate has the value measured along the vertical axis.

The main analysisinf my paper is complemented by analyses of various subsamples, each including different groups of academics, classified by the various countries or regions of the world with which they have been affiliated and, tentatively, by gender. By and large, there are very few differences, suggesting once more the strongly global nature of the international academic market, and the homogenous temperament of internationally mobile academics who should therefore be seen as more akin to their colleagues across the globe than to skilled workers with whom they grew up and went to school.

References

Kerr, S P, W Kerr, Ç Özden and C Parsons (2016), “Global talent flows”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 30(4): 83-106.

Kerr, S P, W Kerr, Ç Özden and C Parsons (2017), “High-skilled migration and agglomeration”, Annual Review of Economics 9: 201-234.

De Fraja, G (2023), “International Mobility of Academics: Theory and Evidence”, CEPR Discussion Paper 18117.

Parey, M, J Ruhose, F Waldinger and N Netz (2017), “The selection of high-skilled emigrants”, Review of Economics and Statistics 99(5): 776-792.

Miguelez, E and C Fink (2013), Measuring the international mobility of inventors: A new database (Vol. 8). WIPO.

Wahba, J and Y Zenou (2012), “Out of sight, out of mind: Migration, entrepreneurship and social capital”, Regional Science and Urban Economics 42(5): 890-903.

Yudkevich, M, P G Altbach and L E Rumbley (2017), International faculty in higher education: Comparative perspectives on recruitment, integration, and impact, Routledge.

Nekoei, A (2013), “Immigrants' labor supply and exchange rate volatility”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 5(4): 144-164.

Mihut, G, A de Gayardon and Y Rudt (2016), “The long-term mobility of international faculty: A literature review”, International Faculty in Higher Education: 25-41.

Teichler, U (2017), “Internationally mobile academics: concept and findings in Europe”, European Journal of Higher Education 7(1): 15-28.