The ‘Great Enrichment’ that Europe experienced after the Industrial Revolution remains a central question in economic history (McCloskey 2016). It is now well established that the European economies’ technological head-start over the rest of world did not start strictly with the Industrial Revolution in the middle of the 18th century, but had already begun with the great transformations of the late 15th and 16th centuries (Broadberry 2015). Yet the exact causes of this growth are still very much in doubt. Clearly, the effect of science properly speaking on economic growth before the 18th century is still limited at best. Yet it would be unwarranted to dismiss the role of knowledge and its dissemination through Europe. In recent work, we argue that efficient institutions for organising apprenticeship provided a crucial foundation for the rise of Europe (de la Croix et al. 2016).

Tacit knowledge and the central role of apprenticeship

Before the Industrial Revolution, almost all useful knowledge was tacit. The main mechanism through which tacit skills were transmitted across generations was apprenticeship, a relationship linking a skilled adult to a youngster whom he taught the trade. Apprentices spent most of their waking hours in the master’s workshop, where they learned from the master and more experienced apprentices and journeymen. As apprentices spent time in the shop, they gradually acquired the skills of the master, often through imitation and guided learning-by-doing (DeMunck and Soly 2007, Steffens 2001). In Figure 1, a 14th century illustration from a dye-shop attests to the medieval origins of the institution, while a 19th century painting by Louis-Emile Adan, “Man and boy making shoes”, illustrates its persistence into the modern era. Apprenticeship was the primary mechanism by which productive human capital was created in the past.

Figure 1 Evidence of the persistence of apprenticeship-based learning in Europe

Differences in the rates of technological progress may in principle have two different sources: differences in the rate of original innovation, and differences in the speed of the dissemination of existing ideas. Our theoretical analysis focuses entirely on the second channel and abstracts from differences in the rate of invention. What we argue is that the institutions governing the intergenerational transmission mechanism were of central importance to the dissemination of best-practice techniques. The nature of the apprenticeship system based on personal contacts and mostly local networks was a central factor in the closing of gaps between best-practice and average-practice techniques. We argue that apprenticeship institutions in Europe led to faster dissemination of best-practice technical knowledge and contributed, ultimately, to Europe’s technological primacy.

The need for apprenticeship institutions

To see why apprenticeship institutions mattered so much, it should be recognised that the contract between master and apprentice was in many ways deficient and incomplete. The master promised to teach his young student the secrets of the trade, in exchange for labour services provided by the apprentice and, at times, a lump sum premium paid by the youngster’s parents or guardian. Yet the exact nature of the skills transferred could never be fully specified in the contract, nor could the diligence and loyalty shown by the apprentice in carrying out his side of the deal. Because of these moral hazard problems, some institution that enforced the contract and arbitrated disputes when they arose was crucial.

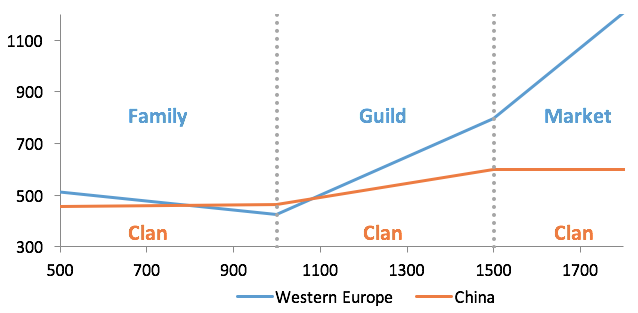

In our analysis, we focus on the apprenticeship system and abstract from other diffusion mechanisms. We distinguish between four types of historically relevant apprenticeship institutions: (nuclear) families, clans, guilds, and markets. In the nuclear family, fathers taught their sons, and hence knowledge was passed only through vertical transmission. In the family equilibrium, the moral hazard problem was resolved (assuming the father to be sufficiently altruistic) but no knowledge was transferred across families, so that the rate of technological progress was very slow. In much of the non-European world, extended families or clans were the fundamental unit of economic organisation among artisans. In this world, the apprentice could learn not just from his father but also from other relatives, depending on the size of the clan. In our model, the clan solved the moral hazard problem because within the clan, people trusted each other and had strong incentives to avoid opportunistic behaviour. Apprentices could learn from any clan members in their chosen trade (and thus could do better than just learning from their fathers). Yet because the clan was limited to people who were related to one another and eventually shared a common ancestor, the diffusion of technology was faster than in a family, but not as fast as when apprentices could learn from the entire population of masters in his town.

Efficient apprenticeship institutions: Guilds and markets

A third form of contract enforcement is through the guilds. In Europe, where craft guilds appeared in the middle ages, the guild enforced apprenticeship contracts, mediated between masters and apprenticeship, and prevented the worst excesses of opportunistic behaviour. The enforcement of contracts and the orderly intergenerational transmission of skills has been cited often by those who have sought to rehabilitate the guilds, traditionally depicted as technologically conservative rent-seeking institutions (Epstein 2008, 2013). Yet historically, the evidence that guilds tried to limit entry into their trade – for instance, by limiting the number of apprentices that each master could take (Trivellato 2008) – is quite strong (Ogilvie 2014). Thus, the diffusion of technology in the guild system was faster than the family or the clan equilibrium, but not as fast as it could be. Still, in the guild system the apprentices could learn from any master. New techniques and innovations could thus spread rapidly across Europe, without being constrained by family lines. The dissemination of ideas was further promoted by institutions such as ‘journeymanship’ (also regulated by guilds), in which apprentices travelled from town to town after their initial training to learn (or in some cases teach) new techniques.

The most efficient institution was one we call ‘market equilibrium’, in which apprentices were free to move about and learn from the best masters (either as apprentices or journeymen), and the most efficient techniques thus disseminated the fastest, without being constrained by the anti-competitive aspect of guilds. The question then arises of how the participants in such market equilibria overcame opportunistic behaviour. The answer is in part that third-party enforcement became increasingly a reality in some parts of Europe, but also that reputation mechanisms assured that cheating by either side would be costly. An illustration of the significance of the four regimes in relation to the rise of Western Europe (relative to the previous leader, China) is provided in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2. Income per capita in Western Europe and China

Source: Maddison (2010).

The four forms of contract-enforcement appeared in many economies side-by-side, but in late medieval and early modern Europe, the guild and market equilibria became increasingly dominant. Thus, the areas that had the most effective apprenticeship institutions were the ones that developed the most progressive and innovative workmanship and experienced the most technological progress even in the absence of major breakthroughs. A recent example is watchmaking in 18th century Britain, where watches became continuously cheaper and better (Kelly and Ó Gráda 2016). But in almost any artisanal trade in Europe – from textiles and ironworking to millwrights and shipbuilding – we observe substantial progress between 1500 and 1750, and knowledge that diffused relatively rapidly (Berg 2007). Some historians have coined the term ‘mindful hand’ to characterise the growing sophistication of the top-of-the-line artisans of the age (Roberts and Schaffer 2007).

It is not surprising, then, that in economies in which apprenticeship was unconstrained and regulated by markets so that knowledge could cross kinship lines, the level of artisanal skills blossomed. This is particularly true for England, where guilds had already been weakened and where the famous 1562 Statute of Artificers, which regulated the parameters of apprenticeship, was widely circumvented (Wallis 2008), but it was also true for the Netherlands (Davids 2003, 2007), the richest economy in Europe for centuries.

Apprenticeship and the Industrial Revolution

A high level of technical competence, as sustained by effective apprenticeship institutions, played a crucial role in the Industrial Revolution. We argue that they were not a sufficient condition for economic growth: on its own, artisanal progress without the infusion of novel radical insights from more formal knowledge would have run into diminishing returns. Still, these institutions might well have been a necessary condition for the take-off. But without the workmanship that could turn blueprints and new designs into working machines and that could scale up models, the insights of the giants of the Industrial Revolution would have been as economically inconsequential as Da Vinci’s brilliant technological sketches. English ironmasters such as John Wilkinson were indispensable if inventors such as James Watt and Samuel Crompton were to turn their ideas into reality and bring about the Industrial Revolution. The French economist Jean-Baptiste Say said it best in 1803: “the enormous wealth of Britain is less owing to her own advances in scientific acquirements … as to the wonderful practical skills of her adventurers (entrepreneurs) in the useful application of knowledge and the superiority of her workmen” (Say 1821, vol. 1). After 1815, British skilled mechanics and technicians swarmed all over the Continent to install and maintain the new machinery. They had been trained through a superior system of apprenticeship.

Outside Europe, the institutions of apprenticeship were far less effective. Kinship relations still dominated many other economies, especially China (Greif and Tabellini 2017). While guilds existed in the Ottoman world, India, and in China, we have found no evidence that they did much more than secure exclusionary rents by prohibiting non-members from entering their industries. Apprenticeship remained largely a family or sectarian affair. This is not to deny that kinship relations remained important in Western Europe as well – but in economic history, degree is everything. Recent work trying to understand the Industrial Revolution and the Great Enrichment that followed it has increasingly focused on upper-tail human capital (Mokyr 2009, Squicciarini and Voigtländer 2015, de la Croix and Licandro 2015). In that story, the human capital of top-level artisans and the way it was produced played a larger role than has been realised so far.

One lesson that our work drives home is that the sharp distinction between ‘institutions’ and human capital, as elements in economic growth (Glaeser et al. 2004), is historically inappropriate. Institutions determined the quantity and quality of human capital formation in past societies, and the nature of these institutions help explain the miraculous enrichment of Europe after the Industrial Revolution.

Summary and significance

One of Western Europe’s core historical features was its reliance on mechanisms and institutions that were not based on kinship relations. When applied to learning institutions, this feature led to the adoption of superior apprenticeship institutions, and thus promoted a fast diffusion of best techniques, and it allowed Western Europe to gain primacy in the centuries leading up to the Industrial Revolution. Tacit knowledge and skills remain relevant in today’s economy. For example, master-apprentice-like relationships are still common in the education of doctors and scientists, and the continuing system of formal apprenticeship in Germany is often credited as one source of the country’s low youth unemployment and general economic success.

One of the great advances in understanding our economic past in the past decades has been that “institutions matter” — but identifying which institutions mattered, what they did, and why they arose in the first place has been a matter of considerable controversy. The institutions governing the intergenerational transmission of skills and tacit knowledge should definitely be part of that narrative.

References

Berg, M (2007), “The Genesis of Useful Knowledge”, History of Science 45, pt. 2, No. 148, pp. 123–34.

Broadberry, S (2015), “Accounting for the Great Divergence”, Working Paper, London School of Economics.

Davids, K (2003), “Guilds, Guildmen and Technological Innovation in Early Modern Europe: The Case of the Dutch Republic”, Economy and Society in the Low Countries Working Papers, No. 2.

Davids, K (2007), “Apprenticeship and Guild Control in the Netherlands, c. 1450-1800”, In S L Kaplan, B de Munck, and H Soly (eds.), Learning on the Shop Floor: Historical Perspectives on Apprenticeship, New York: Berghahn Books, 65–84.

de la Croix, D, M Doepke, and J Mokyr (2016), “Clans, Guilds, and Markets: Apprenticeship Institutions and Growth in the Pre-Industrial Economy”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 11199.

de la Croix, D, and O Licandro (2015), “The Longevity of Famous People from Hammurabi to Einstein”, Journal of Economic Growth, 20 (3): 263–303.

De Munck, B, and H Soly (2007), “Learning on the Shop Floor in Historical Perspective.” In S L Kaplan, B De Munck, and H Soly (eds.), Learning on the Shop Floor: Historical Perspectives on Apprenticeship, New York: Berghahn Books, 3–32.

Epstein, S R (2008), “Craft Guilds, the Theory of the Firm, and the European Economy, 1400-1800.” In S R Epstein and M Prak (eds.), Guilds, Innovation and the European Economy, 1400-1800, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 52–80.

Epstein, S R (2013), “Transferring Technical Knowledge and Innovating in Europe, c. 1200-c. 1800.” In J L van Zanden and M Prak (eds.), Technology, Skills and the Pre-Modern Economy in the East and the West, Boston: Brill.

Glaeser, E L, R La Porta, F Lopez-de-Silanes, and A Shleifer (2004), “Do Institutions Cause Growth?”, Journal of Economic Growth 9, 271–303.

Greif, A, and G Tabellini (2017), “The Clan and the Corporation: Sustaining Cooperation in China and Europe”, Journal of Comparative Economics, forthcoming.

Kelly, M, and C O Grada (2016), “Adam Smith, Watch Prices, and the Industrial Revolution”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 131 (4): 1727–1752.

Maddison, A (2010), “Statistics on World Population, GDP and Per Capita GDP, 1- 2008 AD.” available from http://www.ggdc.net/maddison/oriindex.htm.

McCloskey, D (2016), Bourgeois Equality: How Ideas, Not Capital or Institutions, Enriched the World, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Mokyr, J (2009), The Enlightened Economy, New York and London: Yale University Press.

Ogilvie, S (2014), “The Economics of Guilds.” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 28 (4), 169–92.

Roberts, L, and S Schaffer (2007), “Prefacee”, In S Schaffer, L Roberts and P Dear (eds.), The Mindful Hand: Inquiry and Invention from the late Renaissance to early Industrialization, Amsterdam: Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences, xiii–xxvii.

Say, J-B [1803], (1821), A Treatise on Political Economy, 4th edition, Boston: Wells and Lilly.

Squicciarini, M P, and N Voigtländer (2015), “Human Capital and Industrialization: Evidence from the Age of Enlightenment”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 130 (4), 1825–1883.

Steffens, S (2001), “Le métier volé: transmission des savoir-faire et socialization dans les métiers qualifies au XIXe siècle”, Revue du Nord, 15:121–135.

Trivellato, F (2008), “Guilds, Technology, and Economic Change in early modern Venice”, In S R Epstein and M Prak (eds.), Guilds, Innovation and the European Economy, 1400-1800, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 199–231.

Wallis, P (2008), “Apprenticeship and Training in Premodern England”, Journal of Economic History 68 (3): 832–861.