As if a dam had broken, the snap elections in Greece on 25 January unleashed a flood of explicit demands for forgiveness, relief, structuring and default for the country’s €320 billion pile of government debt. The outcome showed not only how fed up Greeks were with austerity, but also how willing they were to elect a new government of innocent outsiders promising to free them from its yoke – without a clear plan on how to accomplish this. Europe, led by Germany, insists that Greeks meet the conditions under which they were lent €240 billion to tide them over their financial crisis.

Posturing by both sides still gives the impression of a slow-moving train wreck that is only weeks away. Negotiating positions show little room for compromise.

- The Tsipras government was elected on the promise of eliminating austerity and has announced an end to it.

- The creditor side – in the end, European taxpayers – has serious concerns that Greece could reverse vital pro-growth reforms and damage its future ability to create jobs and service its debt.

A unilateral debt write-off for Greece could cause cascading demands for relief in countries that have already turned the corner on the crisis, some of which are considerably poorer.

All agree that the IMF-designed Greek ‘programme’ paid too much attention to short-term austerity, and not enough to pro-growth structural reforms, in its crucial first three years. It meant savage fiscal cuts in an inflexible economy and unnecessary pain. Increases in taxes – regressive and unpopular ones like VAT and uncollectable ones like wealth taxes - have worsened already existing distortions, causing price increases for those who can least afford them and chasing the tax base further underground.

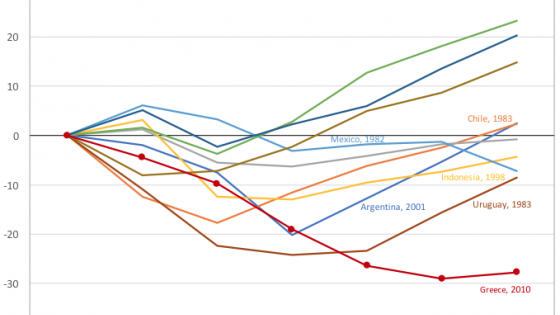

It is crucial to understand that 80% of Greek public debt is in the hands of official creditors already. Europe can easily lighten the short-term debt burden by allowing Greece to refinance at lower interest rates, extended maturities and longer grace periods. Taken alone, however, this type of relief will not bring a sustainable recovery to Greece either. In the long term, only the citizens of Greece have the power to make its debt bearable by building a competitive economy, by raising its trend growth rate with credible labour market and administrative reforms. Higher growth and low concessionary interest rates reduce the need for punishing primary surpluses (Eichengreen and Panizza 2014). The state of the erstwhile ‘sick men’ of Europe – the Netherlands, Belgium, Ireland, Denmark, and Germany – show that such reforms can lay the ground for sustainable growth as well as fiscal rectitude. There is good reason to believe that they will ultimately stimulate demand as well (Fernández-Villaverde and Rubio-Ramirez 2011).

The problem is not only about finding areas of agreement and common ground. It is about simultaneously getting incentives right and making sure European voters are on board, both Greek and non-Greek. That is, finding an accord that will put Greece on a sustainable course towards long-term recovery. A first step towards a deal is thus to realise that the key issue, already recognised by the new government, is sustainability rather than debt. This means competitiveness and the supply side. Demand stimulus alone will not get Greece back on track. A simple debt write-down without addressing the underlying conditions of the Greek economy will only treat the superficial symptoms, paper over an already miserable economic situation with a short-term surge of aggregate demand, and do nothing to change the underlying cause of the malaise. Most importantly in our view, the abandonment of deregulation and privatisation initiatives will ensure that Greece will be back for more money in another three or four years.

New Deal for Greece

We have a concrete proposal which allows both sides to save face and avoid the apparently inexorable train wreck. The ‘New Deal for Greece’ would consist of the following steps:

1) Greece refrains from actions that would breach its commitments under the existing programme agreements, and formally asks for an extension to the deadline of the old programme in which details of a new follow-up deal are hammered out.

2) In exchange for continued product and labour market reforms, Europe eases the targets of the Greek primary surplus, focusing less on austerity and intrusive supervision, and more on supply-driven growth.

The new government, less beholden to vested interests represented by the old parties ND and PASOK, can better tackle cartelised structures.

3) The OECD, a recognised expert on supply-side reforms, is added to the team of monitors of Greek commitment: the ECB for banks and banking, the IMF and EU Commission for fiscal policy, and the OECD on supply-side reforms.

Talking individually to this ‘Quartet’ of institutions rather than as a group, Greece can credibly claim to have ditched the despised Troika.

4) Greece sticks to its plans to make labour markets flexible.

Greece raises the minimum wage in stages and links these increases to an improvement in private sector employment, but maintains lower minimum wages for young people and exempts very small enterprises.

5) Privatisations that have already been slated are carried through.

The EU offers assistance for further sales of state assets in the form of debt-for-equity swaps at terms favourable to Greece. These assets could be sold off later under the auspices of an EU trust fund, under less time pressure and for a better price. Excess proceeds could be returned to the Greek treasury, and be used to retire debt or finance needed infrastructure investment. The poor record of privatisations to date in Greece (Manasse 2014) certainly also reflects the role of inflexible unions and labour markets, giving more reason to stick to labour market reform plans.

6) The EU supplies targeted additional funds for humanitarian relief such as food and medical assistance, infrastructural aid and other technical help.

Concluding remarks

Many proposals circulating in the blogosphere are either impractical or politically impossible to implement. Widespread calls for an international debt conference or generalised debt relief fail to recognise the political pitfalls and bottomless pits. Grexit, on the other hand, involves large and unknown risks to the integrity of the EU, the global financial system and above all to Greece. It is not a serious option, despite the impression that many would rather see it and are even planning for it, for reasons that appear to have less to do with Greece than with the euro and the EU.

It would be a grave mistake and a massive misreading of European history, almost of the order of the events that led to World War I, to let this train wreck happen. A good case can be made that Greece – because it was the first to be pulled into the vortex of the sovereign debt crisis – deserves a little better treatment than other Eurozone debtors (Phillipon 2015). But it also needs to reinvent itself, much like Germany did in 2003 with the Agenda 2010 (Burda 2007). Historic opportunities rarely present themselves as they have now. Europe and Greece need to seize the moment.

References

Burda, M (2007), 'German recovery: it’s the supply side', VoxEU.org, 23 July.

Eichengreen, B and U Panizza (2014), ‘Can large primary surpluses solve Europe’s debt problem?’, VoxEU.org, 30 July.

Fernández-Villaverde, J and J F Rubio-Ramirez (2011), ‘Supply-side policies and the zero lower bound’ VoxEU.org, 11 November.

Manasse, P (2014), ‘Privatisation and debt: Lessons from Greece’s fiasco’, VoxEU.org, 31 January.

Philippon, T (2015), ‘Fair debt relief for Greece: New calculations’ VoxEU.org, 10 February.