Shortly after Britain’s referendum on membership of the EU, Guardian Economics Editor Larry Elliott wrote that “Brexit is a rejection of globalisation” (26 June 2016). His claim about the causes of Brexit is stark, but it is one that is echoed, if usually in slightly more qualified fashion, by many other commentators.

For example, in her Sylvia Ostry Lecture in September 2016, Christine Lagarde, Managing Director of the IMF, put forward similar ideas, with the theme of “Making Globalization Work for All” (Lagarde 2016). In this view, globalisation has brought economic advantage to many, but equally left behind many others. Voting ‘Leave’ in Britain is explained as an expression of the anger of the ‘left behind’.

One obvious qualification to such claims, linking economic disadvantage to Leave voting, is that the (small) Leave majority was most strikingly characterised by its age and educational profile (the older and least educated being strongly pro-Leave), rather than directly by economic conditions (as Lord Ashcroft Polls show). Leave was a clear victory for traditional Conservative voters, many of whom live in the prosperous South of England, rather than in less well-off parts of the country.

Overall, we can perhaps characterise the Leave vote as an alliance between those who favoured ‘taking back control’ and those who saw the vote as a means of expressing opposition to their economic difficulties.

But insofar as Brexit reflected underlying economic discontent, is it helpful to link this to the effects of globalisation? In my view, the answer is that in seeking to understand the economic basis of the Brexit vote, we should concentrate not on globalisation but on the long-term impact of de-industrialisation.

Writing here on VoxEU in August 2016, Diane Coyle said that “[t]he UK's ‘Leave’ vote could be seen as a vote against globalisation and its uneven impact on different parts of the country, rather than a vote specifically against the EU. The proportions voting for Leave were higher in the Midlands and North of England, where de-industrialisation struck hardest and where average incomes have stagnated.” (Coyle 2016)

Such claims reflect a common error of conflating globalisation and de-industrialisation, a confusion that ignores the clear historical evidence of the way that de-industrialisation began long before the current phase of globalisation. Globalisation has contributed to de-industrialisation, but it is only one contributor, and historically not the most important.

De-industrialisation (a fall in the share of employment in the industrial sector) began in Britain in the 1950s. It was driven by shifts in patterns of demand and technological change, most strikingly in increasing the growth of productivity (and lowering the relative price) of manufactured goods.

Since 1948, the annual increase in labour productivity in services has been around 1.48%; in manufacturing, it has been 2.78%. (‘Industry’ is normally defined as manufacturing, plus mining plus construction. Mining has almost disappeared, but construction has come to employ almost as many workers as manufacturing; productivity growth in construction is significantly slower than in manufacturing).

Note that the focus here is on industrial employment, not industrial output. Indeed, industrial output has not fallen, but grown slowly on trend, so it is now at an all-time high.

Table 1 Proportion of workers in industrial employment in the UK

| 1957 |

48% |

| 1979 |

38% |

| 1998 |

27% |

| 2016 |

15% |

Peak employment in British industry came in the late 1950s, while peak employment in manufacturing alone came in the following decade. These broad trends have affected all industrial countries, so that industrial employment has fallen substantially even in successful industrial countries with a manufacturing trade surplus, such as Germany. Industrial employment has fallen more slowly in Germany than in Britain but, as a share of the total, it has more than halved since its peak in 1970.

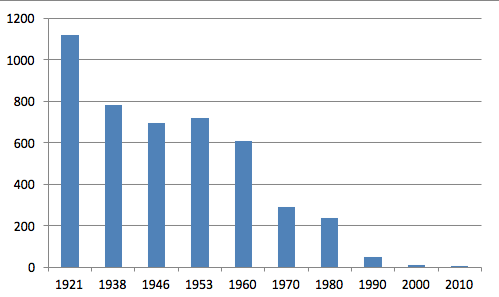

The long-run nature of these trends is illustrated by the fact that many more coal-mining jobs were lost in Britain under Harold Wilson’s government of the 1960s than under Margaret Thatcher’s government of the 1980s. These trends reflected the collapse in industrial and domestic uses of coal, and latterly the shift away from coal in electricity generation.

Figure 1 Employment in coal in Britain

It is true that with the decline of the British coal industry (deep-mining of coal ended in 2016), Britain has become a coal importer, with 25 million tons of imports in 2015. But if we ask how many jobs would be created if that coal were produced at home, the number would be perhaps 12,500. This is not a trivial number, but it would only take employment back to the level of the year 2000, and, of course, leave the numbers a tiny fraction of the industry’s previous size.

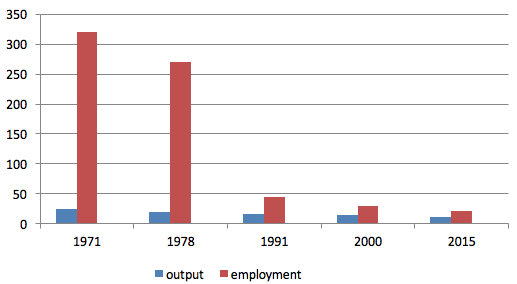

The history of the steel industry is also highly instructive. Figure 2 shows employment in this industry (the red bars, in 000s of workers) alongside output (the blue bars, in millions of tons). Iron and steel has lost 95% of its workforce since 1971, the great bulk of the fall coming in the 1980s (50% of the fall in 1979-1981). Over the same period, output fell by 50%.

Two points about this history should be stressed. First, Britain still produces a considerable amount of steel, but huge increases in productivity (and changes in the composition of output) mean that this can be produced with far fewer workers. Second, the fall in output owes little to the Chinese competition that has been so much emphasised in recent policy discussions. There was no big surge of Chinese imports until the 2000s; indeed, China was a steel importer well into the 1990s.

Figure 2 The British steel industry: Employment and output

Similar stories of long-run decline could be told of textiles and clothing, and shipbuilding. But also important is the story of more characteristically ‘modern’ industries such as car manufacturing. Like iron and steel, output has diminished since the early 1970s peak, but it has revived since the Global Crisis to well over 90% of that peak (though the composition of output has of course altered significantly). Again though, because of productivity gains, far fewer workers are needed to produce a car than was the case 40 years ago. While today car manufacturing directly employs around 140,000 workers, in 1972 the figure was half a million.

The loss of jobs through de-industrialisation matters because the service sector, which has largely replaced industry, offers far more polarised types of employment. While historically industry provided many secure and relatively well-paid jobs for those with low educational qualifications (but often with very high levels of industry-specific skills), most service activities offer much less to those who lack a high level of such qualifications.

The number of very good jobs has grown in parts of the service sector, but it has been paralleled by the rapid growth in numbers of poorly paid and often insecure jobs in such areas as care services and retailing. This deterioration in the labour market has been met by an enormous growth of in-work benefits, (alongside housing subsidies), creating a wage-subsidy system costing around £30 billion per annum.

What I have described as a ‘new Speenhamland’ system (Tomlinson 2015) has brought a striking volte-face in Conservative politics, with the attempt to switch some of the costs of raising sub-poverty level wages on to employers by a statutory ‘Living Wage’. (The Conservatives were bitterly opposed to a legal minimum wage when Labour proposed it in the 1990s; it was enacted in 1998). But this shift in policy has only slightly dented the public expenditure cost.

Shifts in demand and technology, more than globalisation, have led to de-industrialisation. Serious errors of policy have undoubtedly accelerated this process, and compressed it into short time periods (most obviously, the extraordinary appreciation of the pound in 1979-81 as a result of the Thatcher government’s policies). But overall the process has not mainly been policy-driven.

In responding to the economic problems that underpinned the Brexit vote, it is important to be clear that globalisation is only one part of the story. To put it crudely, if globalisation were somehow reversed, it would not return Britain to having anything like the number of industrial jobs that existed in the 1950s (or the 1980s).

Some increase in industrial jobs is of course possible, including by the expansion of such sectors as renewable energy. But the idea of a wholesale ‘re-industrialisation’ that would offset the effects of the profound changes in demand and productivity of recent decades is fantastical.

While there are certainly powerful arguments for seeking to offset the impact that globalisation has had on particular groups of workers, the biggest challenge is how to make a service-dominated economy deliver much better outcomes for those who currently occupy the many low-quality jobs in the service sector.

References

Coyle, D (2016), "Brexit and globalisation", VoxEU.org, 5 August.

Lagarde, C (2016), “Making Globalization Work for All”, Sylvia Ostry Lecture, Toronto, 13 September.

Tomlinson, J (2015), “De-industrialisation, ‘new Speenhamland’ and neo-liberalism”, VoxEU.org, 05 July.