How have the average real income gaps between countries evolved over the centuries? The debate over this has heated up since the 1990s. First, Angus Maddison’s global estimates of product per capita put numbers on the orthodox impression that Western Europe has been far ahead of other regions since at least the Middle Ages (Maddison 1995, 2001). Then a series of Great Divergence revisions has suggested that much of Asia had been close to Western Europe in living standards until the Europeans established hegemony there. At the turn of the century, Kenneth Pomeranz argued that China had been virtually even with Western Europe and Japan until the British and others moved in during the 19th century (Pomeranz 2000, 2011). India around 1600 was also near Western Europe in real income, and even ahead of Japan, before the British arrived. On this elevation of pre-British India, the revisionists implicitly agreed with Maddison (Maddison 1995, 2001, 2010; Parthasarathi 2005; Broadberry et al. 2006).

In a recent study, I sometimes take sides in the debate and sometimes disagree with both sides (Lindert 2016). Digging deeply into historical data from six continents at benchmark dates, and extending a new technique for comparing countries in the past (pioneered by Ward and Devereux 2003), allows us to minimise some well-known index number frustrations and establishes the directions in which past estimates were biased.

I suggest a re-shuffling of the global ranks between Columbus and WWI. Four results stand out in terms of the ability to buy just the basics of life, on which we have the most price history, and a fifth reinforces them:

1. The real income gap between Northwest Europe and the major Asian countries was greater since the 1500s than even Maddison had estimated.

2. Contrary to all previous estimates, Mughal India around 1600 was already far behind both Japan and Northwest Europe.

3. Within Europe, the new estimation procedure shows little bias in Maddison’s estimates.

4. Average incomes in North America were already higher than in Britain or France in the late 17th century, long before Maddison’s c.1900 catching up date for the US versus Britain. A similar ‘frontier advantage’ has now emerged from estimates for Australia in 1870.

5. Adding what is known about the ability to buy luxuries and capital goods raises the income of Western Europe relative to all other regions, except possibly resource-rich North America.

Knowing how countries’ real purchasing powers differed in the past is a less daunting task if we look at the comparison as people would have seen it then. Early modern observers like Britain’s Gregory King or Adam Smith asked which countries could more easily afford the basics of life, especially food grain. Of course, their comparisons faced the eternal index number problem posed by the multiplicity of commodities: which country’s expenditure weights should be used? Yet it is much easier to confront the index number problem once than to confront it thrice. Angus Maddison tried to compare any two countries’ past real incomes in three steps, first comparing their purchasing powers in 1990, and then using the two countries’ separate time series of real product per capita. The three steps require building index numbers using three different sets of commodity bundles. It is far easier, and more appropriate to historical contexts, to stick with direct current-price comparisons of the countries’ nominal incomes per capita back then, deflated by prices people paid back then. This is the approach I adopt.

To build a price denominator for historical comparisons, one seeks prices of widely traded commodities that changed little in quality between countries and over time. This is possible for the necessities of life. Accordingly, a literature on comparative real wages has focused on ‘bare bones’ necessities, with the lead being taken by Robert Allen and co-authors (Allen 2001, Allen et al. 2011, 2012). To allow comparisons of the costs of staples in distant lands, Allen and others had to confront the fact that different countries have separate diets and separate fuels (e.g. Asian rice versus European bread, and firewood or sunshine versus coal heating). They solved this by redefining the necessities in terms of those deliverables, such as food calories and BTU of heat. I adopt their cost-of-deliverables procedure in the next section in order to exploit the wide availability of prices for such basic necessities. Yet I use it to evaluate the average purchasing power of the entire population, not just of common labourers, whose position in society varied greatly between regions.

The ability to buy staples

The historical real-income ranks can be revealed in two stages. First, let us take advantage of the broad availability of staple-good prices by putting numbers on the ability of an average nominal income (GDP per capita) to buy only those staples, those ‘bare-bones’ necessities. Then, in the next section, we shall see that this narrow cost-of-living concept reveals, or understates, the historical contrasts between regions’ ability to buy all goods and services.

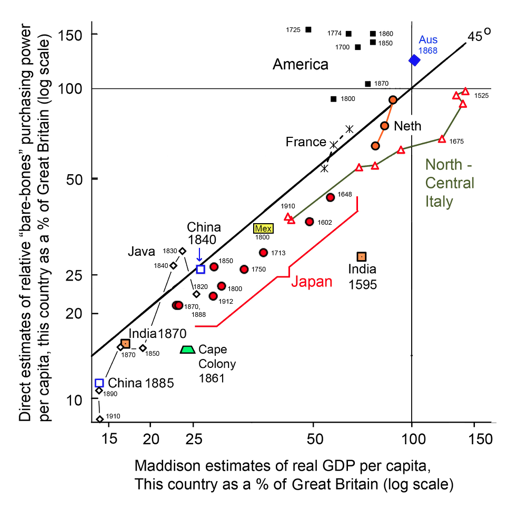

If every country’s purchasing power is contrasted with that of data-rich Britain, how would the contrast in their average abilities to buy staples stack up against the contrast in their real incomes per capita using the conventional Maddison estimates? The ‘dueling disparities’ diagram, Figure 1, gives the answer for a host of data-supplying country-years between Columbus and WWI. The horizontal axis plots the conventional Maddison estimates of each country’s real GDP per capita as a percentage of that for Britain. The vertical axis plots the new ability of nominal GDP to buy a bare-bones subsistence bundle of goods, again as a percentage of that for Britain. If the new estimates perfectly agreed with Maddison, all historical disparities relative to Britain would lie along the 45-degree line. They don’t.

Figure 1 Duelling disparities: Current price measures of relative purchasing power per capita versus Maddison’s GDP per capita, several countries relative to Britain, 1525–1912

Notes: Omitted here, but covered in Lindert (2016) are the new estimates for Mexico 1800, Peru 1800, and Poland 1578.

Source: Lindert (2016), backed up by estimates and data citations detailed at http://gpih.ucdavis.edu/PP.htm.

The poor countries of the Eastern Hemisphere were even poorer relative to Britain than Maddison implied. The Japanese, for a start, had a lower relative ability to buy staple goods than Maddison implied, especially before the Meiji Restoration. So says Figure 1, by following Japanese data benchmark years from 1602 down to 1912. India’s relative purchasing power around 1600, before the British arrived, has been overstated even more seriously, not only by Maddison (2001) but also by more recent writers. It was already behind Japan at that time, not ahead of Japan. Java was also poorer than Maddison thought – but only from 1890 on, in the later colonial era. Before 1890, the Javanese had a better relative purchasing power, mainly because the island’s fertile soils were still being rapidly settled. As for China, the jury is still out on Maddison’s estimates, since we lack independent estimates for the Ming and Qing reigns before 1840.

Among the rich countries, Maddison seems to have got most of his European comparisons right, aside from his overrating Swiss incomes. Yet he got some rankings wrong in the contrast between Northwestern Europe and its overseas frontier settlements, as suggested by the dueling disparities in the upper right-hand corner of Figure 1. Britain’s North American colonies were already ahead of Britain in average incomes before 1774, with or without the slave and native populations (Lindert and Williamson 2016). The population of Quebec could buy more staples than the average Parisian between 1688 and 1760 (Geloso 2015). And by 1870, Australians had clearly higher incomes than the British, not just parity as Maddison and others implied (Figure 1 and Panza and Williamson, forthcoming). There has been a general tendency to underrate the living standards on the food-rich frontiers, a point already implicit in Figure 1’s results for Java before 1850.

The ability to buy luxuries

One might ask: But couldn’t the disagreements between the new estimates and Maddison’s estimates be blamed on the new estimates’ use of a narrow price deflator, covering just some staple goods? That would be true if the scarcity of luxury products (and capital goods) behaved in a way contrary to the scarcity of staples, with luxuries being relatively cheaper in poorer countries than in rich countries.

Yet the opposite was true, as far as we can tell. Guns, ships, and most other modern goods were cheaper in Western Europe than anywhere else in the world for most of the period before 1914. While product heterogeneity complicates most international comparisons, we can follow the historical geography of a few relatively unchanging luxuries and capital goods. The two parts of Figure 2 do so, by following the prices of modern paper, iron, and nails relative to wheat, a classic staple good. What Figure 2 shows very clearly is that these luxury goods were not cheaper, but rather dearer, in all poorer countries in centuries past. Therefore, having omitted these luxuries and capital goods does not explain away, but rather reinforces, the Eastern Hemisphere contrasts in purchasing power that were unveiled in Figure 1. As for the contrasts between Western Europe and its new overseas settlements, including luxuries would not necessarily change the new findings, since resource abundance on the frontier cheapened some luxuries and capital goods.

Figure 2 The wheat price of some luxury and capital goods: England versus elsewhere over the centuries

A) The wheat price of paper

B) The wheat price of iron and nails

Notes: Omitted here, but covered in Lindert (2016) are the new estimates for Mexico 1800, Peru 1800, and Poland 1578.

Source: Lindert (2016), backed up by estimates and data citations detailed at http://gpih.ucdavis.edu/PP.htm.

Behind it all: Balassa-Samuelson, Gerschenkron, and Engel

Why should direct historical comparisons of purchasing power have widened the Eurasian gaps in centuries past, while merely changing some relative ranks among the rich?

Three mechanisms driving the biases in the conventional measures of Maddison and some others should be familiar to economists specialising in trade and growth. A key permissive condition relates to the fact that before 1870 most goods, including staple goods, were not traded between the major regions of the world. This lack of trade magnified the Balassa-Samuelson effect, whereby non-traded goods are cheaper in poorer countries to a degree missed by comparing the prices in the small traded-good sector. A second mechanism was the Gerschenkron effect, through which the more one relies on the latest-period price weights, as Maddison was forced to do, the more one understates the earlier international divergences by under-weighting the modern luxuries and capital goods. Finally, this understatement of early divergences is magnified by the non-linearity of Engel effects. Before 1914, not only did poorer countries spend more on staples like rice or wheat, but the gap in expenditure shares was far wider then than it is today. By choosing post-war expenditure weights, Maddison missed the wider implications of the price differences between luxuries and staples. Going back to history for the direct comparisons that Gregory King, Adam Smith, and others pondered at the time gives a true view of how countries’ relative purchasing powers have changed.

References

Allen, R C (2001), “The Great Divergence in European Wages and Prices from the Middle Ages to the First World War.” Explorations in Economic History 38, 4: 411–47.

Allen, R C. J-P Bassino, D Ma, C Moll-Murata, and J L van Zanden (2011), “Wages, Prices, and Living Standards in China, 1739-1925: in comparison with Europe, Japan, and India” Economic History Review 64, S1: 8-38.

Allen, R C, T E Murphy, and E B Schneider (2012), “The Colonial Origins of Divergence in the Americas: A Labor Market Approach”. Journal of Economic History 72, 4 (December): 863-94 and supplementary materials.

Broadberry, S, B Campbell, A Klein, M Overton, and B van Leeuwen (2015), British Economic Growth, 1270-1870. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Broadberry, S, J Custodis, and B Gupta (2015), “India and the Great Divergence: An Anglo-Indian Comparison of GDP per capita, 1600–1871.” Explorations in Economic History 55: 58–75.

Geloso, V (2015), “The Seeds of Divergence: The Economy of French America, 1688 to 1760.” PhD thesis, London School of Economics and Political Science, September.

Lindert, P H (2016), “Purchasing Power Disparity before 1914.” NBER working paper 22896, December.

Lindert, P H and J G Williamson (2016), Unequal Gains: American Growth and Inequality since 1700. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Maddison, A (1995), Monitoring the World Economy 1820-1992. Paris: OECD.

Maddison, A (2001), The World Economy: A Millennial Perspective. Paris: OECD, Development Centre Studies.

Maddison, A (2010), www.ggdc.net/maddison/Historical_Statistics/horizontal- file_02-2010.xls.

Parthasarathi, P (2005), “Agriculture, Labour, and the Standard of Living in Eighteenth-Century India”, in R C Allen, T Bengtsson, and M Dribe (eds), Living Standards in the Past: New Perspectives on Well-Being in Asia and Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 99-110.

Pomeranz, K (2000), The Great Divergence: China, Europe, and the Making of the Modern World Economy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Pomeranz, K (2011), “Ten Years After: Responses and Reconsiderations”, Historically Speaking, 12(4), 20-25.

Project Muse, https://muse.jhu.edu/login?auth=0&type=summary&url=/journals/historically_speaking/v012/12.4.coclanis.html

Ward, M and J Devereux (2003), “Measuring British Decline: Direct Versus Long-Span Income Measures”. Journal of Economic History 63:3 (September): 826-51.