Among high-skilled professionals, gender gaps in earnings and a lack of female representation in senior positions persist (e.g. Bertrand and Hallock 2001, Manning and Swaffield 2008, Bertrand et al. 2010). This is the case even for individuals with similar educational backgrounds and training. This raises several questions. To what extent are gender gaps in career outcomes attributable to differences in performance? Does family responsibility play a role in gender differences in performance? Are other factors, like career ambition, responsible for differences?

There is a large and growing academic and public debate on why large gaps in earnings and promotion exist among more able and career-driven men and women (see, for instance, the ongoing public debate between Sheryl Sandberg 2009, 2013 and Anne Marie Slaughter 2012, 2015). In a new paper, we help shed light on these questions, using detailed and objective measures of performance, for high-skilled workers (Azmat and Ferrer 2016)

The data: Young US lawyers

Using data on a representative cohort of young lawyers in the US, we study gender gaps in performance, earnings, and promotion to partner level at a law firm. We focus on a generation of lawyers that has experienced virtual gender equality in law school admissions and no prominent gender differences in law school performance.1 However, as in other professions and industries, the legal profession has a persistent gender earnings gap. Figure 1 illustrates the gender difference in lawyers’ salaries in the US, which has persisted over time.

Figure 1 Evolution of lawyers’ gender gap in earnings, 2000-2010

Note: Median weekly earnings for lawyers in the period from 2000 to 2010. Current Population Survey’s Household Data, detailed by occupation (Bureau of Labor Statistics, US).

Since the performance measures are transparent and homogeneous across firms and areas of specialisation, we can study performance gaps for different firms’ characteristics, regions, and areas of expertise. On the basis of widely used measures of performance in law firms, we find that male lawyers bill 10% more hours to clients. For hours billed, we find that the gender gap in performance is relatively stable throughout the performance distribution. We find that male lawyers bring in more than twice the amount of new business to the firm than female lawyers. For raising new client revenue, the gender gap is generally significant, but there is some evidence that it is largest at the top of the distribution.

Performance gap and the pay gap

We show that performance gaps explain a substantial share of the gender gaps in earnings and eventual promotion to law firm partner. In our data, the raw earnings gap between male and female lawyers is 18 log points. Individual and firm characteristics explain 50% of this initial gap. Including the two measures of performance used in the legal profession helps explain a sizable share – approximately half of the remaining gender gap.

We also analyse the link between performance and gender gaps in career advancement. Our measure of career advancement is whether lawyers have achieved partnership status 12 years after law school. In our raw data, we see that male lawyers are approximately 10% more likely to obtain partnership status than female lawyers. We show that performance measured earlier in the lawyers’ career is positively and significantly associated with the likelihood of becoming partner, explaining approximately 40% of the gap. Moreover, once performance is accounted for, the gender gap in partnership status is no longer statistically significant.

Why do female lawyers bill fewer hours?

An important next step is to understand the key determinants of the gender gaps in performance. We investigate a number of hypotheses for why female lawyers may not be billing as many hours or raising as much new client revenue as male lawyers. Part of the main explanation is the differential effect of the presence of pre-school aged children on female and male lawyers.

We find that having young children results in female lawyers billing fewer hours but does not affect male lawyers. In particular, we find that female lawyers with young children bill approximately 200 fewer hours per year, while male lawyers with young children do not experience a significant decline in the number of hours billed.

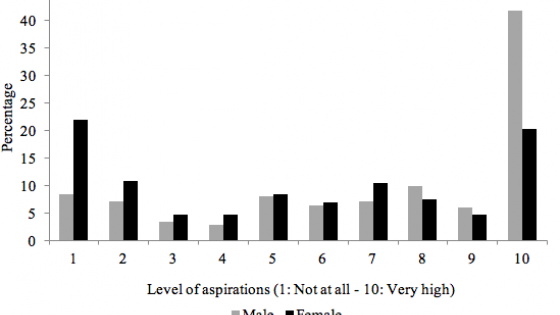

The presence of young children is not, however, the only key determinant of gender gaps in performance. A substantial share of the gender gap in performance is explained by a gender gap in aspirations to be promoted (Figure 2). Male lawyers have stronger aspirations to make law firm partner than female lawyers, and this explains an important part of the gender performance gap.

Figure 2 Aspirations of becoming partner

Note: Percentage of responses by gender to the question: “How strongly do you aspire to attain an Equity Partner position within your firm?” with possible answers ranging from 1: Not at all to 10: Very high (After the JD study, 2007)

The gap in aspirations of becoming a law firm partner continue to play this role for the gender performance gap even after taking into account contemporaneous reverse causality concerns – addressed by predicting current aspirations of becoming a partner using measures that are correlated with aspirations but pre-date most of the lawyers’ time in the legal profession.

Gender differences exist in other dimensions, such as area of specialisation, tendency to overbill, time spent networking, and time spent working on weekends. While these factors influence performance, they do not appear to explain the gender gaps in performance.

In addition, we find that possible channels of direct discrimination in law firms – whereby, for instance, senior lawyers (i.e. law firm partners) could influence lawyers’ performance by assigning more or less cases to junior colleagues – are not strong determinants of performance gaps. Studying diverse channels of potential discrimination, we do not find strong evidence of performance gaps being driven by discrimination at the workplace.

Nevertheless, the main determinants of performance differences – children and career aspirations – might be associated with subtle forms of discrimination, such as compliance with traditional gender roles.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our results reveal the central role of gender gaps in performance for the analysis of gender differences in career outcomes and its determinants. One potential implication is that gender-based inequality in earnings and career outcomes might not decrease in the near future – and could even increase – as more high-skilled workers are explicitly compensated based on performance. Thus, performance pay could lead to higher inequality not only across male workers, as shown by Lemieux et al. (2009), but also across males and females. Still, the net effect of performance pay in gender inequality is ambiguous as higher earnings flexibility via performance pay could favour female labour participation in high-skilled professions.

References

Azmat, G, and R Ferrer (2016), “Gender Gaps in Performance: Evidence from Young Lawyers”, Journal of Political Economy, forthcoming

Bertrand, M, and K F Hallock (2001), “The Gender Gap in Top Corporate Jobs”, Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 55 (1), 3-21

Bertrand, M, C Goldin, and L F Katz (2010), “Dynamics of the Gender Gap for Young Professionals in the Financial and Corporate Sectors”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 2, 228-55

Lemieux, T, W B MacLeod, and D Parent (2009), “Performance Pay and Wage Inequality”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124, 1-49

Manning, A, and J Swaffield (2008), “The Gender Gap in Early-Career Wage Growth”, Economic Journal, 118 (530), 983–1024

Sandberg, S (2009), Don't Leave before you Leave, Fortune

Sandberg, S (2013), Lean In: Women, Work and the Will to Lead, New York: Alfred A. Knopf

Slaughter, A M (2012), "Why Women Still Can't Have it All", Atlantic, July/August

Slaughter, A M (2015), Unfinished Business: Women, Men, Work, Family, Random House

Endnotes

[1] Female lawyers now account for approximately 50% of law school graduates (Digest of Education Statistics, 2008) and 45% of law firm associates (NALP, 2008). Males have slightly higher performance on law school standardised admission tests (the LSAT), by approximately 2%, compared with female test-takers (Dalessandro et al. 2010). Nevertheless, there are no significant gender difference in law school performance such as by GPA, ranking of the law school attended, participation in editorial activities, moot trials, and judicial clerkship programs.