In the UK, as in other countries, there has been a rapid increase in the number of non-native speakers. In England the number of non-native speakers has increased by a third in the last decade. Now, roughly one in nine children between the ages of five and 11 do not speak English as a first language. A significant driver of this change has been immigration, though the trend has also been influenced by higher birth rates among ethnic minority groups.

The Netherlands

As discussed by Ohinata and van Ours (2013a), the perception in the UK media is that the influx of immigrants has put teachers under strain. This raises the question as to whether non-native speakers have a detrimental influence on their native-speaking peers. Ohinata and van Ours consider this question in a Dutch context and find there to be no such spillover effect. This is all the more interesting because immigrant students in The Netherlands come from families with lower education.

New research on England

The situation is different in England, where the foreign-born population has higher education on average compared to the native-born population (Dustmann and Glitz 2011). Thus in England, there might be things about the children of immigrants – such as having better educated parents – that can compensate for any lack of language fluency at an early age. In that case, we would be even less inclined to think that native English speakers would suffer from having such children as their peers.

Our research analyses a census of all children in English schools – the National Pupil Database – to explore these issues (Geay et al. 2013). We use pupils in primary school between 2003 and 2009, focusing on their outcomes when they take a national test at age 11. We look at whether there is an association between the proportion of non-native English speakers in a year group and the educational attainment of native English speakers at the end of primary school – and whether it can be interpreted as a causal relationship.

Our approach identifies a causal impact if all relevant controls are added, leaving only idiosyncratic variation in the percentage of non-native English speakers within the same school across cohorts of pupils in the final year of primary school (Year 6). This is similar to the strategy used by Hoxby (2000) and many other papers that try to identify peer group effects. In general, the strategy seems plausible in this context (although we do make use of a second identification strategy – discussed below).

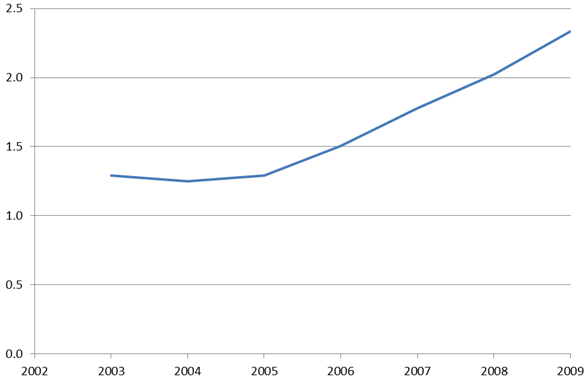

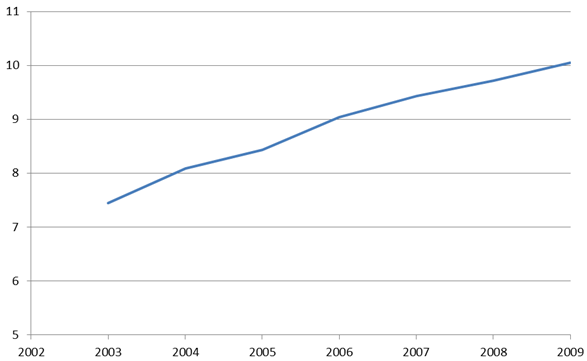

We also split the data into white and non-white non-native speakers to see if there might be different effects. Although the latter group is more important numerically, the former has grown very sharply after the eastern enlargement of the EU in 2005. The evolution during the time period of our data is shown in Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1. Percentage of children (Year 6) who speak ‘English as an additional language’ and are of white ethnic origin

Figure 2. Percentage of children (Year 6) who speak ‘English as an additional language’ and are of non-white ethnic origin

We find a modest negative correlation in the raw data between the educational attainment of native English speakers and the proportion of non-native speakers in their year group. This correlation is halved once the demographic characteristics of native English speakers have been controlled for. It disappears altogether once the type of school attended by non-native English speakers has been controlled for.

This means that the negative correlation in the raw data reflects the fact that non-native English speakers typically attend schools with more disadvantaged native speakers. Once this fact has been taken into account, there is zero association between their presence in greater numbers and the educational attainment of their native English-speaking peers.

This result also holds true for younger cohorts (age seven instead of age 11) and when looking at the number of languages spoken in the year group instead of the percentage of non-native English speakers. We explore many different aspects of heterogeneity, for example, looking at native English speakers who are disadvantaged, who are of low ability and who are based in London.

We also divide non-native English speakers into those who appeared in the school census in the last two years of primary school versus those who were in the school census before that time. This affects the raw association between the percentage of non-native English speakers and the educational attainment of native English speakers. But once demographics of native speakers and school controls are added, the effects go to zero in almost every case.

Catholic schools

We also use another strategy to look at the relationship between the percentage of white non-native English speakers and the educational attainment of native English speakers. This strategy uses the fact that the number of white non-native English speakers grew dramatically after the EU’s eastern enlargement in 2005.

Since many of the new immigrants were Polish (and likely to be Catholic), there was a big rise in the demand for Catholic schooling. The data show a much larger increase in the percentage of white non-native English speakers in (state) Catholic schools after 2005 compared with other schools. This is shown in Figure 3. We use this fact as the basis of an Instrumental Variable strategy where the interaction between year and sector identifies the ‘white, non-native’ effect in Catholic schools.

Figure 3. Percentage of children (Year 6) who speak ‘English as an additional language’ and are of white ethnic origin; by school type

This ‘natural experiment’ provides a way to see if there were consequences for the relative educational attainment of native English speakers in Catholic schools. The results for reading and writing show no clear impact, but there is some evidence for a small, positive effect in the case of maths. In other words, native English speakers at Catholic schools that saw a strong relative increase in white non-native speakers benefited to a small extent in their maths results.

A possible reason for this result may be the fact that immigrants from eastern European countries are better educated and more attached to the labour market than the native population (Dustmann et al. 2010). The children of such immigrants may be a welcome influence in the schools they attend.

The two different research strategies apply to different populations. The first shows associations that are applicable to all schoolchildren. The second – making use of eastern enlargement – only estimates the effects on native English speakers in Catholic schools who were exposed to an increase in white non-native speakers after EU enlargement. Thus, the latter results cannot be extrapolated to other contexts.

Conclusions

But both strategies suggest that negative effects of non-native English speakers can be ruled out. Thus, the growing proportion of non-native English speakers in primary schools should not be a cause for concern: this trend is not detrimental to the educational attainment of native English speakers.

References

Dustmann, C, Frattini, T, and Halls, C (2010), “Assessing the fiscal costs and benefits of A8 migration to the UK”, Fiscal Studies 31, 1-41.

Dustmann, E, and Glitz, A (2011), “Migration and education”, in E Hanushek, S Machin and L Woessmann (eds.) Handbook of the Economics of Education 4.

Charlotte Geay, Sandra McNally and Shqiponja Telhaj (2013), ”Non-native Speakers of English in the Classroom: What are the Effects on Pupil Performance?”, Economic Journal, August.

Hoxby, C (2000), “Peer effects in the classroom: learning from gender and race variation”, NBER Working Paper. No. 7867.

Ohinata, A and van Ours, J (2013a), “How immigrant children affect the academic achievement of native Dutch children”, VoxEU.org, 25 July.

Ohinata, A and van Ours, J (2013b), “How immigrant children affect the academic achievement of native Dutch children”, Economic Journal, August.