Immigrants potentially foster international trade by reducing trade costs. Such frictions are quantitatively large, especially for poor countries (Anderson and van Wincoop 2004), and recent research has singled out information costs in particular as inhibiting trade flows (Chaney 2011, Allen 2012, Steinwender 2013). Immigrants may lower such frictions through their knowledge of their home country's language, regulations, market opportunities, and informal institutions. So too are immigrants argued to decrease the costs of negotiating and enforcing contracts by drawing upon their trusted networks, thereby deterring opportunistic behaviour in weak institutional environments (Greif 1993, Gould 1994, Rauch 2001, Rauch and Trindade 2002, Dunlevy 2006). Migrants are thus typically expected to facilitate bilateral trade mostly with developing countries, where firms typically need to navigate a myriad of bureaucratic and legal hurdles, Vietnam being a case in point.

While a large literature examines the pro-trade effect of migration, causality from migration to trade has yet to be conclusively established (Felbermayr et al. 2012). Studies almost ubiquitously uncover a positive correlation between migration and trade, to the extent that these results are often interpreted as evidence of a positive diaspora externality. Doubts persist, however, as to whether trading partner's cultural affinity or else bilateral economic policies might be driving the observed positive correlations (Lucas 2005, Hanson 2010). These doubts are valid, not least since the estimated impacts of immigration on trade are quantitatively large, therefore representing an important economic channel through which migrants might lead to substantial gains from trade.

New evidence from a natural experiment

To address these endogeneity concerns, in new research we use the exodus of the Vietnamese boat people to the US as a natural experiment to establish a clear causal effect from Vietnamese immigration to US trade with Vietnam (Parsons and Vézina 2014). The exodus started in April 1975, following the fall of Saigon to the communist North Vietnamese, when the US military evacuated around 130,000 refugees from South Vietnam.

A major part of this evacuation was Operation Frequent Wind, the largest boat and air lift in refugee history. This first wave of refugees was exogenously dispersed throughout the US as US policymakers, drawing on the lesson from the agglomeration of Cubans in Miami ten years earlier, were keen to avoid the development of a similar Vietnamese refugee agglomeration. The US government and voluntary agencies oversaw their resettlement and in most cases decided their destinations. The dispersion gave rise to Vietnamese communities in places such as New Orleans, Oklahoma City, Biloxi, Galveston, and Kansas City, which had previously received few immigrants from Asia (Zhou and Bankston 1998). It constituted the first of many waves, as subsequently hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese refugees fled Vietnam to escape protracted persecution in ‘re-education camps’ and agricultural collectives. Between 1975 and 1994, around 1.4 million Vietnamese refugees were resettled in the US. Concurrently, the US imposed a trade embargo on Vietnam, under the auspices of the 1917 Trading with the Enemy Act and the 1969 Export Administration Act.

Our natural experiment thus combines a large immigration shock of Vietnamese refugees to the US – the first wave of which was exogenously dispersed across US states – in tandem with a lasting trade embargo. These events constitute an ideal setting to test the causal link from Vietnamese immigration on US exports to Vietnam following the lifting of the trade embargo in 1994.

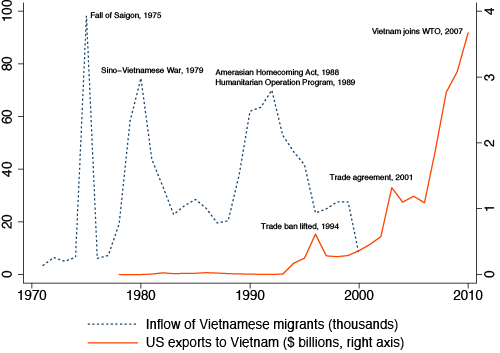

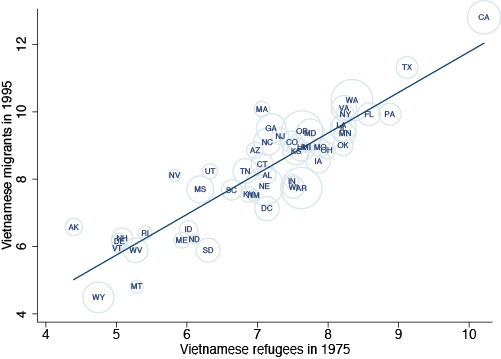

Figures 1 and 2 pictorially demonstrate our identification strategy. Figure 1 plots the waves of of Vietnamese immigration to the US (dotted line), with three spikes corresponding to the fall of Saigon, the Sino-Vietnamese War, and later the introduction of US policies designed to welcome additional waves of Vietnamese refugees. These massive immigration shocks preceded the opening up of trade with Vietnam in 1994, which led to a rise in US exports to Vietnam (bold line) that was particularly pronounced in the late 2000s. Figure 2 shows that the exogenous allocation of the first wave of 130,000 refugees in 1975 is strongly correlated with the location of Vietnamese migrants in the US in 1995, the first year after the lifting of the trade embargo. We thus use the chronology of events and the exogenous allocation of the first wave of refugees (as an instrumental variable) to establish a causal link from migrant networks in 1995 to trade creation between 1995 and 2010.

Figure 1 Vietnamese inflows to the US and US exports to Vietnam

Figure 2 1995 Vietnamese migrant stock vs. 1975 refugees

Note: The circles are proportional to the state's average exports to Vietnam as a share of total exports during 1995-2010.

Results

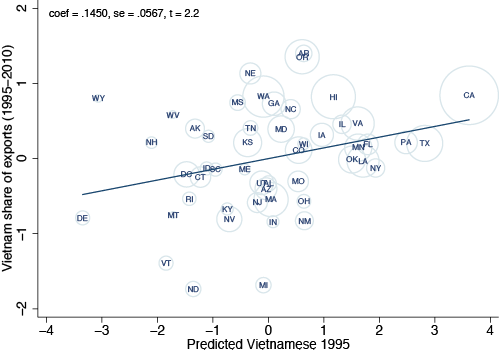

Our results show that the share of US exports going to Vietnam over the period 1995-2010, i.e. following the lifting of the trade embargo in 1994, was higher and more diversified in those states with larger Vietnamese populations, themselves the result of larger refugee inflows two decades beforehand. We find that states with larger Vietnamese populations, measured in either levels or as shares of state populations, total migrant stocks or Asian migrant stocks, are associated with greater exports to Vietnam, whether expressed as shares of state GDP or total exports, or as the share of industries with positive exports, i.e. the extensive margin. Our results, which are robust to controlling for income per capita, remoteness from US customs ports, and export structure, suggest that a 10% increase in the Vietnamese network raises the ratio of exports to Vietnam over GDP by 2%, and the share of total exports going to Vietnam by 1.5% (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. The causal pro-export effect of the Vietnamese

Note: The circles are proportional to the State's Vietnamese population share in 1995.

Abundant anecdotal evidence also suggests the overseas Vietnamese take an active role in fostering trade between the US and Vietnam. One particularly poignant example is that of David Tran, once a major in the South Vietnamese army, who fled from Vietnam in 1979 following the Sino-Vietnamese war. After time in a United Nations refugee camp, he arrived in the US in January 1980. After settling in Los Angeles, he established Huy Fong Foods, naming his company after the Taiwanese freighter on which he left Vietnam. Chief among Huy Fong Foods' products is Sriracha sauce, a global brand which totalled sales of $60 million in 2012. Strikingly, 80% of these sales were exports to Asia. Tran is just one example among hundreds of thousands of entrepreneurial Vietnamese settled in the US from 1975 onwards that foster trade with Vietnam. Many Vietnamese businesses provide information and business services to US multinationals wishing to do business in Vietnam and help them navigate through a multitude of legal hurdles. For example, the first companies that established long-distance telephone and flight services to Vietnam after 1994, drastically reducing information barriers between the two countries, were founded by Vietnamese migrants.

Conclusion

Our paper represents, to the best of our knowledge, the first cogent evidence of a causal link from immigration to exports, drawing on a natural experiment. Building upon Gould's (1994) seminal insight, our results lend further support to the idea that immigrants are fundamentally differentiated from native populations in terms of the ties with their home nations. These ties, maintained by a common language and regular flows of information, bring nations closer together and represent an important channel through which immigrants nurture long-run development.

References

Allen, T. (2012), “Information Frictions in Trade,” mimeo.

Anderson, J. E. and E. van Wincoop (2004), “Trade Costs,” Journal of Economic Literature, 42, 691–751.

Chaney, T. (2011), “The Network Structure of International Trade,” NBER Working Papers No. 16753, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

Dunlevy, J. A. (2006), “The Influence of Corruption and Language on the Protrade Effect of Immigrants: Evidence from the American States,” The Review of Economics and Statistics, 88, 182–186.

Felbermayr, G., V. Grossmann, and W. Kohler (2012), “Migration, International Trade and Capital Formation: Cause or Effect?” IZA Discussion Papers 6975, Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA).

Gould, D. M. (1994), “Immigrant Links to the Home Country: Empirical Implications for U.S. Bilateral Trade Flows,” The Review of Economics and Statistics, 76, 302–16.

Greif, A. (1993), “Contract Enforceability and Economic Institutions in Early Trade: the Maghribi Traders’ Coalition,” American Economic Review, 83, 525–48.

Hanson, G. H. (2010), “Chapter 66 - International Migration and the Developing World,” in Handbooks in Economics, ed. by D. Rodrik and M. Rosenzweig, Elsevier, vol. 5 of Handbook of Development Economics, 4363 – 4414.

Lucas (2005), International Migration and Economic Development: Lessons from Low-income Countries, Edward Elgar.

Parsons, C. and P.L. Vézina (2014), “Migrant Network and Trade: The Vietnamese Boat People as a Natural Experiment”, Economics Working Paper 705, University of Oxford

Rauch, J. E. (2001), “Business and Social Networks in International Trade,” Journal of Economic Literature, 39, 1177–1203.

Rauch, J. E. and V. Trindade (2002), “Ethnic Chinese Networks In International Trade,” The Review of Economics and Statistics, 84, 116–130.

Steinwender, C. (2013), “Information Frictions and the Law of One Price: When the States and the Kingdom became United,” CEPREMAP Working Papers 1314, CEPREMAP.

Zhou, M. and C.L. Bankston (1998), Growing Up American: How Vietnamese Children Adapt to Life in the United States, Russell Sage Foundation Press.