The origins and the historical evolution of the gap in economic performance and living standards between Italy's north and south remains an unsettled issue in Italian economics and politics. Until recently, mainstream Italian economic historiography inferred the existence of a sizeable gap at the moment of the unification on the basis of anecdotal evidence that documented the backwardness of the south. In recent years, a number of popular historians, who style themselves as a ‘neo-borbonic’ cultural (and political) movement, have dissented vociferously. They claim that in 1861 there was no gap in either living standards, economic performance, or development potential. They argue that the historical roots of Italian economic dualism are to be found in the harsh ‘colonial' policies designed and implemented by the ruling elites in the north to the detriment of the south.

The most recent economic history literature on the questione meridionale (“the southern question”) has moved away from sweeping generalisations based on shreds of quantitative and qualitative evidence toward a comprehensive and systematic quantitative appraisal of the dimensions of economic performance and living standards.

This effort has so far been unable to settle the issue, because there is insufficient data on output in the early decades of the unified Italy. According to Daniele and Malanima (2007, 2011), at the time of Italy's unification, the level of GDP per capita was similar all over the country, and the north-south gap remained narrow for at least 20 years. In contrast, Felice (2014) estimated that the gap between the north-centre and the south of the country was already 18% in 1871, and thus probably also in 1861, and that it grew to about 26% by 1911. Evidence about other dimensions of living standards, such as life expectancies, literacy rates, and heights has supported this interpretation (Felice and Vasta 2015, Vecchi 2017).

The real wages evidence

In a recent paper, we examine real wages for unskilled male workers instead of output (Federico et al. 2017). Real wages have been frequently used by economic historians as a convenient proxy for economic performance and standard of living. The intuition underlying this approach is that real wages may not be a comprehensive representation of the economic system, but they portray the economic fortunes of a significant and revealing segment of society.

We have estimated series of real wages at provincial level from unification to WWI following the method introduced by Allen (2001). Real wages are computed as 'welfare ratios', the annual earnings of unskilled worker divided by the cost of a 'bare bone basket' for a family. The basket is designed to give each consumption unit the minimum amount of food to work, at the lowest possible cost, plus the barest minimum for lodging, clothing and fuel. Expressing real wages as welfare ratios has the advantage of setting out the results in an informative way (how many bare bone baskets could a worker afford to buy with annual earnings?) that can be used to make straightforward comparisons over time and space. Figures 1 and 2 compare Italian real wages, computed as welfare ratios, internationally.

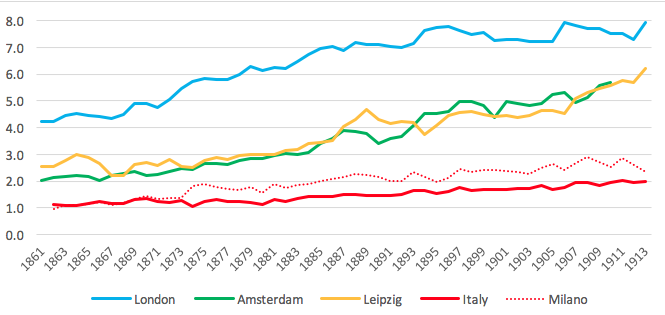

Figure 1 Real wages (welfare ratios) in comparative perspective: Italy versus developed countries, 1861-1913

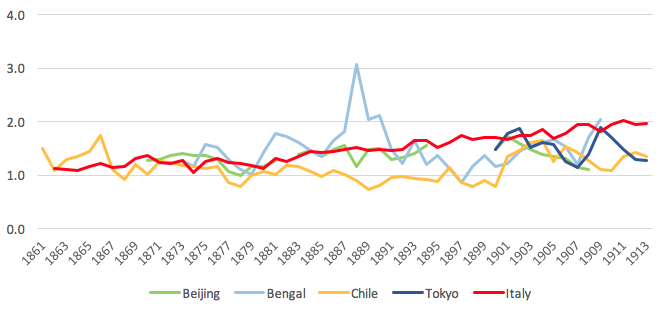

Figure 2 Real wages (welfare ratios) in comparative perspective: Italy versus less developed countries, 1861-1913

Figure 1 shows a large gap in real wages between Italy and the most developed European countries before 1913. Until the early 1880s, the Italian welfare ratio remained around 1.2, meaning an unskilled labourer working full-time could earn a little more than what was necessary to support his family at the minimum subsistence level. The welfare ratio reached 1.5 for the first time in 1888, and fluctuated around 1.6-1.7 until the early 1900s. Thereafter it started to grow, with some acceleration, but on the eve of WWI, the welfare ratio was still less than 2. In London, by comparison, it was between 7 and 8.

Italian workers appear to have been quite poor even when compared with less-developed countries in other continents (Figure 2). Until the 1880s, the Italian welfare ratio was stuck at the same level of most of the countries. After the 1890s it to reached, and in some cases surpassed, the level of urban wages in Japan and China. At the outbreak of WWI, Italy's welfare ratio was slightly above the level of other less-developed countries in the sample.

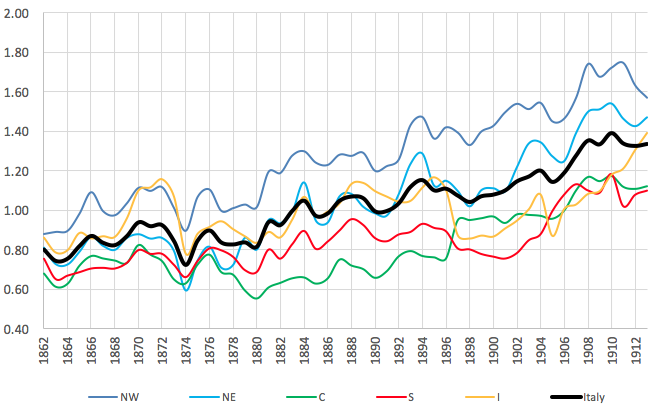

Figure 3 Real wages (welfare ratios) by macro-areas, 1861-1913

Figure 3 sets out our main estimates of real wages for five main macro-regional areas of Italy during this time. They are the north-west, north-east, centre, south, and islands. As described by the conventional wisdom, we find that the regional divide was already large at unification. Northern wages were about 15% higher than southern wages, inclusive of the islands, and 20% higher if we consider only the mainland south. This implies that the origins of the Italian north-south divide preceded political unification and were rooted in the long-run economic history of the different areas. We also did not find any support for the notion of a sudden and drastic impoverishment of the south after 1861.

The islands and the centre merit some additional comments. The low level of real wages in the centre is consistent with the evidence on incomes for sharecroppers, who accounted for a large majority of the agricultural workforce of this area. Sharecroppers received incomes in kind as lodging, and they had an implicit right to be subsidised if they were in distress. Furthermore, market wages were reduced by the supply of labour from members of sharecropping households moonlighting for causal work. A similar argument accounts for the relatively high level of real wages in the islands relative to wages in the continental south. In Sicily, the agricultural workforce clustered since the Middle Ages in very large agglomerations (‘agro-towns’). This pattern of settlement prevented women from seeking agricultural employment. Low employment rates for women created higher wages for males to guarantee the survival of the household. The sharp rise of wages in the early 1870s reflects very tight labour markets for unskilled construction workers caused by a massive wave of public works, especially in railways.

The drivers of real wages growth, 1871-1911

Figure 3 also shows that, after the 1880s, there was an acceleration in the growth of real wages in the north-west, whereas in the other macro-regions similar growth of real wages took place only after 1900. We looked for causes by running a standard growth regression model of real wages between 1871 and 1911 (data constraints prevented us using more complex specifications). We considered the five most important drivers of economic change according to the literature: human capital (proxied by literacy rates), social capital, market potential, endowments of water resources, and transport infrastructure (as proxied by the railway extension). We found that the only consistently significant and positive variable was human capital. The estimated coefficient implies a massive effect of human capital on real wages. Moving from the province with lowest literacy rate, Caltanissetta in Sicily (8.3%) in 1871 to the province with the highest literacy rate, Turin (57.7%) would add 3.7 points to the growth rate of real wages. In this counterfactual scenario, real wages in Caltanissetta in 1911 would have been 3.4 times higher than their initial level.

The Italian economic history of real wages bears out, once more time, the key role played by human capital as a fundamental cause of long-run economic growth. Given the dismal record in public education of the South (85.6% of illiterates at unification according to Vecchi 2017), neo-borbonic nostalgia for an imaginary lost prosperity, and the narrative of stifled southern development potential, are clearly untenable.

References

Allen, R (2001), “The great divergence in European wages and prices from the Middle Ages to First World War”, Explorations in Economic History 38: 411-447.

Daniele, V and P Malanima (2007), “Il prodotto delle regioni e il divario Nord-Sud in Italia (1861-2004)”, Rivista di Politica Economica 97: 267-315.

Daniele, V and P Malanima (2011), Il Divario Nord-Sud in Italia 1861-2011, Soveria Mannelli: Rubbettino.

Federico, G, N Alessandro and M Vasta (2017), “The origins of the Italian regional divide: evidence from real wages, 1861-1913”, CEPR Discussion paper 12358.

Felice, E (2014), “Il Mezzogiorno fra storia e pubblicistica. Una replica a Daniele-Malanima”, Rivista di Storia Economica 32(2): 197-242.

Felice, E and M Vasta (2015), “Passive modernization? The new human development index and its component in Italy’s regions (1871-2007)”, European Review of Economic History 19: 44-66.

Vecchi, G (2017), Measuring Wellbeing: A History of Italian Living Standards, Oxford: Oxford University Press.