Worldwide migration numbers in 2015 exceeded expectations, reaching close to 244 million (UNDESA 2016). These growing population flows have contributed to a shift in both the political discourse and in the scientific research agenda, bringing the analysis of the economic implications of migration to the fore. Most of this research has concentrated on the economic impact of migrants on both their own futures and those of locals (e.g. Card 2005), on changes to the local labour market and its dynamics (e.g. Bijak et al. 2007), or on public finances (e.g. Kerr and Kerr 2011). The focus of these studies, however, has typically been the short term. Our understanding of the economic implications of population mobility has been limited to the first five to 15 years after the initial migration. The analysis of the medium- to long-term impact of migration on economic prosperity has been mostly neglected. Only in recent years have researchers started to address this gap. In particular, our previous work has demonstrated how current levels of economic development across the US still depend on migration settlement patterns that took place over 100 years ago, regardless of national origin (Rodríguez-Pose and von Berlepsch 2014, 2015). Sequeira et al. (2017) recently confirmed the significance of this relationship.

One important demographic aspect related to migration has, however, remained firmly anchored in short-term scrutiny: diversity. As formerly homogeneous communities become more diverse following migration, the question of whether more diverse societies facilitate or deter growth has become more prominent. Research on the economic impact of population diversity has flourished, focusing on a multitude of transmission channels ranging from skill variety, social interaction, innovative networks, institutions, and the provision of public goods to trust, social participation, social unrest, and conflict (e.g. Ottaviano and Peri 2006, Alesina et al. 2016, Kemeny and Cooke 2017). Most of this research unveiled a considerable effect of diversity on growth over the short-term.

However, whether population diversity levels generated by past migration waves affect economic outcomes over the medium and long term has remained an untouched area of research. Our recent paper aims to fill this gap (Rodríguez-Pose and von Berlepsch 2017).

We seek to ascertain whether areas of the US that were characterised by a large population diversity more than a century ago are wealthier today than those that remained more homogenous in their population composition. The basic questions behind the analysis are:

- Does having a very diverse population at one point in time lead to persistently higher levels of economic growth?

- Is the economic impact of diversity only evident in the short term, vanishing once the different population groups become part of the society’s ‘melting pot’?

We assess these questions by examining the extent to which the high degree of cultural diversity in US counties generated during the Age of Mass Migration of the late 19th and early 20th centuries has left an enduring impact on the economic development of those US areas that witnessed the greatest heterogeneity in population.

Migration and diversity in the US during the Age of Mass Migration

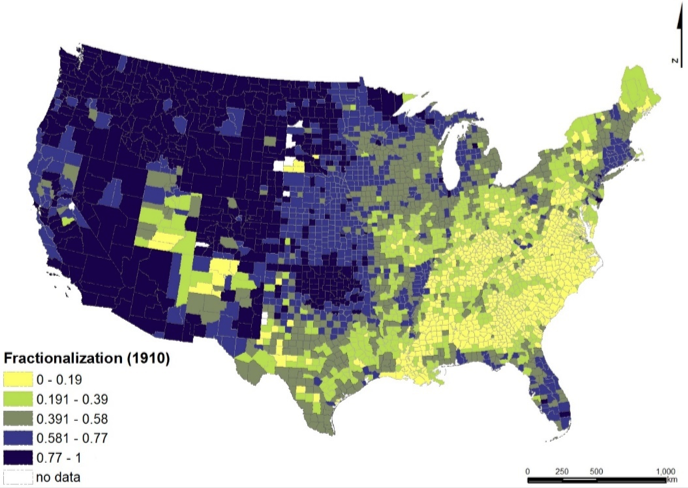

Between the US Civil War and the mid-1920s – a period known as the Age of Mass Migration – close to 30 million Europeans crossed the Atlantic and settled in the US. At the time, virtually no legislation existed which restricted European migrants from entering the country, meaning that newcomers, regardless of nationality, could roam freely and settle wherever they wished. The result was that migration drastically reshaped the population composition of the US. Within a few decades, the population of some US counties changed from being almost completely local-born to rates of well in excess of 50% of the population born elsewhere in the US or abroad (Figure 1).

However not all areas were affected in the same way. High levels of population diversity became the norm primarily in the west of the country (with the exception of parts of New Mexico, Texas, and Utah), while huge swaths of the old South remained demographically homogeneous. Cities in the North East, such as New York City and Boston, hosted vibrant, mixed migrant communities. By contrast, other areas in the North East, such as Maine, Vermont, or parts of upstate New York, were characterised by low population diversity levels (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Diversity in the composition of the US population by county in 1910 (population fractionalisation index)

How has population diversity affected local economic performance?

To what extent have differences in population diversity at the time affected local economic performance in the US? We examine:

- the extent to which the levels of initial diversity – using the two most popular proxies of population diversity, namely, fractionalisation and polarisation – between 1880 and 1910 across US counties have left a long lasting economic legacy that can still be identified in the economic development of US counties today, and

- whether any positive or negative influence of initial diversity has waxed or waned with time.

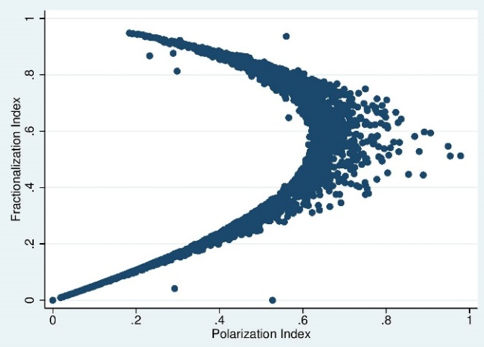

Following the literature, population diversity, measured as fractionalisation between different groups, would lead to positive economic outcomes by creating a fertile ground for new ideas, innovation, and productivity (Kemeny and Cooke 2017). Diversity could, by contrast, also have a polarising effect, upsetting the coordination of actors and their communication, generating animosity, enlarging differences in preferences, and creating situations of conflict. All these factors could undermine the economic potential of places (Montalvo and Reynal-Querol 2005). The relationship between both indices in any given year adopts a non-linear D shape (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Fractionalisation versus polarisation across US counties in 1910

We conduct the analysis using birthplace data at county level of the years 1880, 1900, and 1910. The data are extracted from the IPUMS USA database. The birthplaces of a representative, weighted population sample of 5,791,531 individuals in 1880, 3,852,852 individuals in 1900, and 923,153 individuals in 1910 are aggregated and allocated to the counties of residence of the individual. As the number and size of US counties change over the period of analysis (2,875 counties in 1880, 3,090 in 1900, and 3,123 in 1910), counties at the time of migration are matched to their 2010 equivalent using US Census Bureau cartographic boundary files of the 48 continental states. This implied calculating historical averages weighted by population density following a county boundary change.

Two sets of control variables are introduced in the econometric model. The first one comprised factors which influenced a county’s development at the time of the big migration waves. The second set represents contemporary factors which affect the level of economic development of present day counties. The econometric analysis is conducted both by means of OLS and IV analysis.

Diversity and long-term economic prosperity

The results of our analysis identify the presence of a strong and very long lasting impact of diversity on county-level economic development. Counties that attracted migrants from very diverse national and international origins over a century ago are significantly richer today than those that were marked by a more homogeneous population. Highly diverse counties after the Age of Mass Migration strongly benefited from the enlarged skillset and the different perspectives and experiences the arriving migrants brought with them and from the interaction among those different groups. The result was a surge of new ideas and a newfound dynamism that was quickly translated into lofty, short-term economic gains. These gains proved durable and, albeit in a reduced way, can still be felt today.

Yet the benefits of diversity came with a strong caveat: the gains of having a large number of groups from different origins within a territory (fractionalisation) only materialised if the diverse groups were able to communicate with one another (low polarisation). Hence, past population diversity in the US has become a double-edged sword: it has worked only where the different groups were able to interact, that is, in those places where the ‘melting pot’ really happened. Where such ‘bridging’ did not occur, groups and communities remained in their own physical or mental ghettoes, undermining any economic benefits from a diverse environment.

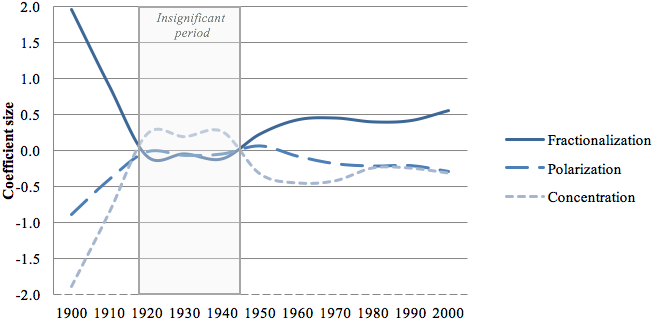

Moreover, the benefits from diversity have remained over time. Where high levels of diversity have been coupled with ‘bridging’ across groups – high population fractionalisation with low polarisation – the associated economic gains were felt in the short, medium, and long term. With the exception of the highly turbulent 1920s to 1940s, a strongly positive and robust impact of fractionalisation on regional income levels, as well as a negative one of polarisation is evident (Figure 3). The only change in this enduring relationship is that both connections, while remaining strongly statistically significant, became weaker after the 1920s.

Figure 3 Evolution of the coefficients for population fractionalisation, polarisation and concentration over time (IV, base year 1880)

Policy implications

Even though the conditions and circumstances today do not correspond to those in the US in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the results represent an appeal for pause and thought in a period when migration policies are fast changing and have often become driven by populist parties and the tabloid press. At a time when many developed countries are rapidly closing down their borders to immigration, trying to shield what – particularly in the case of Europe and Japan – are still rather homogeneous populations from external influences and the perceived security, economic, and welfare threats often unjustly associated with migrants, restricting migration will limit diversity and is bound to have important and long-lasting economic consequences. By foregoing new migration, wealthy societies may be jeopardising not only the short-term positive impact associated with greater diversity, but also the enduring positive influence of diversity on economic development.

The large, positive, and persistent impact of societal diversity on economic development seen in the US would therefore be difficult to replicate – something that ageing and lethargic societies across many parts of the developed world can ill afford. However, if migration is to be encouraged, it is of utmost importance that mechanisms facilitating the dialogue across groups and, hence, the integration of migrants are in place to guarantee that diversity is transformed into higher and durable economic activity over the short, medium, and long term.

References

Alesina, A, J Harnoss and H Rapoport (2016), “Birthplace diversity and economic prosperity”, Journal of Economic Growth 21: 101-138.

Bijak, J, D Kupiszewska, M Kupiszewski, K Saczuk and A Kicinger (2007), “Population and labour force projections for 27 European countries, 2002–2052: Impact of international migration on population ageing”, European Journal of Population 23(1): 1-31.

Card, D (2005), “Is the new immigration really so bad?”, Economic Journal, 115(507): 300-323.

Kemeny, T and A Cooke (2017), “Urban Immigrant Diversity and Inclusive Institutions” Economic Geography 93(3): 267-291.

Kerr, S and W Kerr (2011), “Economic Impacts of Immigration: A survey” Finnish Economic Papers 24(1): 1-32.

Montalvo, J and M Reynal-Querol (2005b), “Ethnic Polarization, Potential Conflict, and Civil Wars”, American Economic Review 95(3): 796-816.

Ottaviano, G and G Peri (2006), “The economic value of cultural diversity: Evidence from US cities”, Journal of Economic Geography 6(1): 9-44.

Rodríguez-Pose, A and V von Berlepsch (2014), “When Migrants Rule: The Legacy of Mass Migration on Economic Development in the United States”, Annals of the Association of American Geographers 104(3): 628-651.

Rodríguez-Pose, A and V von Berlepsch (2015), “European Migration, National Origin and Long-term Economic Development in the United States”, Economic Geography 91(4): 393-424.

Rodríguez-Pose, A and V von Berlepsch (2017), “Does population diversity matter for economic development in the very long-term? Historic migration, diversity and county wealth in the US”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 12347.

Sequeira, S, N Nunn and N Qian (2017), "Migrants and the Making of America: The Short- and Long-Run Effects of Immigration during the Age of Mass Migration", NBER Working Paper No. 23289.

UNDESA (2016), International migration report 2015: Highlights. ST/ESA/SER.A/375, New York: United Nations.