Recent years have seen surging support for populist parties and policies across the advanced countries. Anti-elite sentiment, nationalism, opposition to globalisation, and scepticism about supranational institutions are challenging the international economic order that emerged from World War II. The same scepticism and, in some places, outright hostility is evident in attitudes towards the European Union. Does this mean that the EU is at risk of disintegration?

The rise of populism has been attributed to several factors, from the effect of international trade on the distribution of income (e.g. Colantone and Stanig 2016, Dippel et al. 2015) to the impact of the financial crisis in reducing trust in governments and transnational institutions (Funke et al. 2016) and the effects of rising immigration on native populations (e.g. Dustmann et al. 2005).

In the first report in CEPR’s Monitoring International Integration series, Europe’s Trust Deficit: Causes and Remedies, we analyse the roots of the decline in trust in both national and European political institutions, as reflected in the rise of populist politics.

Download Europe's Trust Deficit: Causes and Remedies here

Listen to Christian Dustmann and Barry Eichengreen discuss the report in a Vox Talk interview here

Populism and trust in national and European institutions

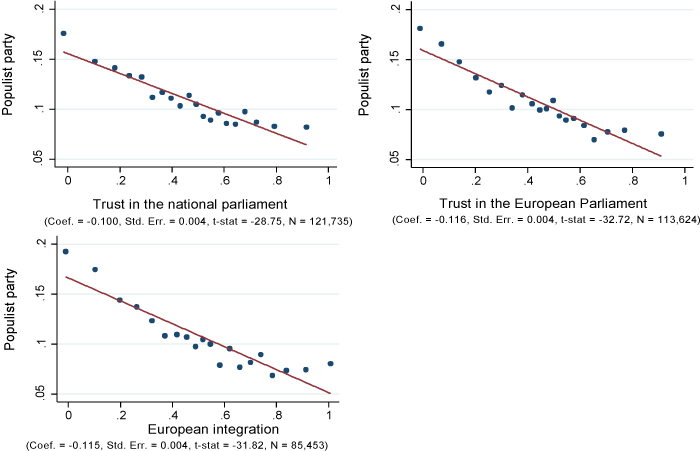

We first show that lack of trust in national and European political institutions is a defining feature of populism. We exploit data from the European Social Survey (ESS) between 2002 and 2014-15 for the EU15 countries. Individuals who vote for populist parties (on the right or on the left), these data suggest, have little trust in national and European parliaments and oppose European integration. This is evident even after controlling for the age, gender, and educational attainment of the individuals in question, as well as for year and country effects. Each dot in the upper-left panel of Figure 1 shows the average probability of having voted for a populist party in the last general election for a given level of trust in the national parliament, holding age, gender and educational attainment constant and controlling for time trends and country differences. The figure makes these patterns clear.

Figure 1 Correlation between voting for populist parties and trust attitudes towards national and European institutions

Notes: The figure shows binned scatterplots and a linear regression line based on OLS regressions. The vertical axis of each panel reports the likelihood of voting for a populist party. The horizontal axis reports the value of the respective attitude variable. Each dot represents the mean of the x-axis and y-axis variables within each bin. To calculate the bins, the variable on the x-axis is split into 20 equal sized groups.

Source: Own calculations based on the European Social Survey (ESS).

Regional and time patterns in trust and anti-EU votes

Why has trust in European and national political institutions declined in recent years, and why have voters turned to anti-EU parties? To address these questions, we exploit regional and time variation in attitudes and electoral outcomes.

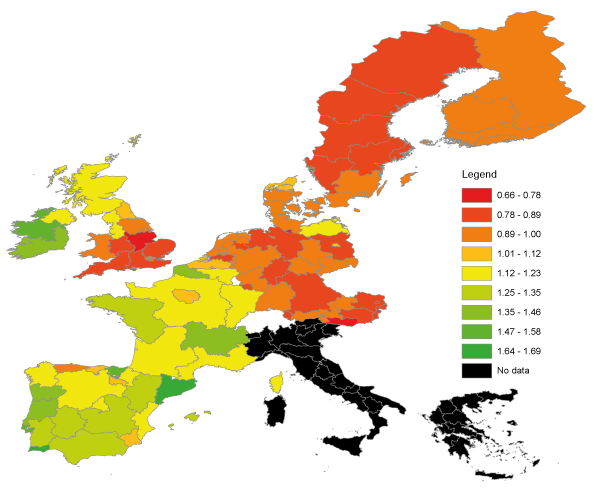

From the ESS, we construct regional averages of attitudes towards national and European political institutions. Figure 2 depicts the ratio of trust in the European Parliament to trust in the national parliament for European regions in 2014/15. Greenish (reddish) colours denote higher (lower) trust in the European Parliament than national parliaments. While data for Italy and Greece are missing in the 2014-15 ESS wave, they are available in earlier waves and are solid green, indicating more trust in the European Parliament than in the national parliament. People in northern Europe have more trust in their national parliament more than in the European Parliament, while the opposite is true in Mediterranean countries. (The opposite is also true, interestingly, in Scotland.) This pattern is consistent with data on the perceived quality of domestic political institutions, which are ranked lower in southern Europe: trust in national political institutions is lower where they are perceived to be less effective.

This pattern hides the underlying distribution of trust in each institution, which varies across individuals. Investigating this in more detail shows that Germans tend to be quite trusting of the European Parliament, although they trust their own parliament even more. The same is true of the Scandinavian countries, where trust in political institutions is high. England is an outlier in distrusting the European Parliament more than most other countries, while trusting its own parliament.

Figure 2 Trust Ratio across NUTS regions in Europe, 2014/15

Notes: The Trust Ratio is the ratio of trust in the European Parliament to trust in the national parliament.

Source: Own calculation based on the European Social Survey (ESS), wave 7.

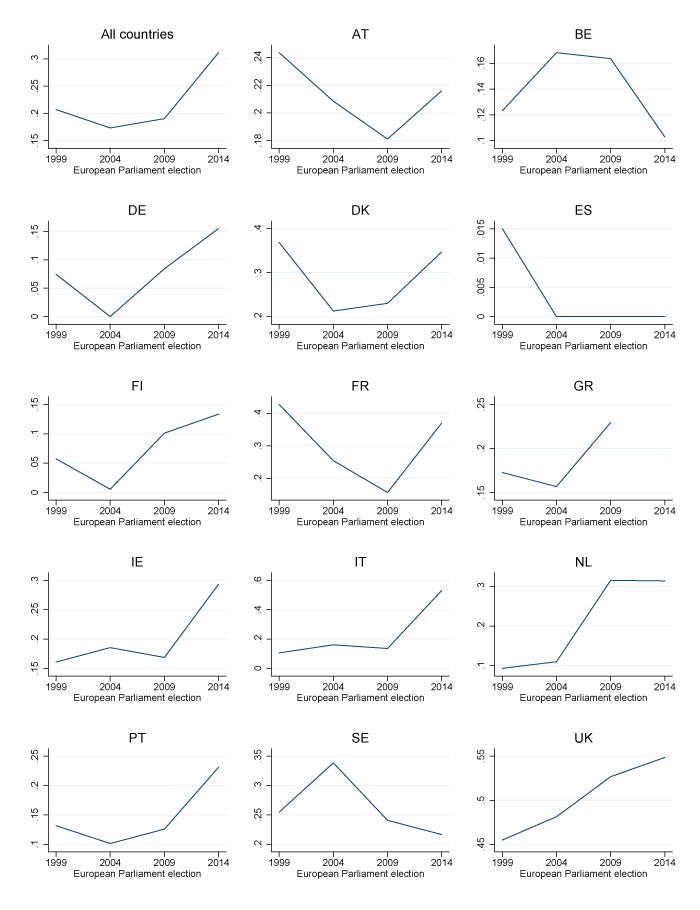

To investigate the trend in vote shares for anti-EU parties across different member states, we construct the share of regional votes for anti-EU parties in elections to the European Parliament between 1999 and 2014, based on the classification of anti-EU parties in the Chapel Hill Experts Survey (CHES).1 Figure 3 shows average vote shares in each country and the EU as a whole. Anti-EU parties gained votes in most countries in 2014. Nevertheless, only in the UK and Italy did they surpass the 50% threshold, while in the EU as a whole they reached just 30% in 2014. The change between 2009 and 2014 is largest in Italy.

The rise in the anti-EU vote share could be due to a change in how votes are allocated between parties, or to a change in the policy platforms of those parties, with some previously pro-EU parties becoming anti-EU. The data suggest that it is voters, not parties, that changed. In most countries, the position of the main political parties did not become markedly anti-EU.

Figure 3 Vote shares of anti-EU parties in elections to the European Parliament

Source: Own calculations based on the European Election Database (EED) and the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES).

Where do distrust and anti-EU sentiment come from?

To address this question, we first examine individual survey data. Our main finding is that older birth cohorts and less-educated individuals are less trusting of national parliaments and the European Parliament, are less supportive of the EU, and are more likely to vote for populist parties. The fact that older people are less pro-Europe is not well known. Sometimes it is argued, to the contrary, that younger individuals are less appreciative of the EU because their memory of World War II is weaker, but in fact the opposite is true. This observation is encouraging for the future of Europe, since over time the older, more Eurosceptic cohorts will be replaced by younger more pro-Europe cohorts – assuming of course that the pattern in the data reflects a specific birth cohort rather than a general age effect.

Turning to regional averages of attitudes and electoral outcomes, we explore their correlation with macroeconomic outcomes such as unemployment and GDP per capita. As economic conditions deteriorate, trust in parliaments drops, more pronouncedly for national parliaments than the European Parliament. But while adverse macroeconomic shocks explain a large fraction of the observed drop in trust in national parliaments, they explain a much smaller fraction of the recent changes in the electoral success of anti-EU parties. The electoral effects of adverse macroeconomic shocks are stronger in southern Europe, particularly after the recent financial crisis.

In addition, more authoritarian and traditional cultural traits amplify the negative effects of adverse macroeconomic conditions on trust in political institutions. In regions with more liberal and modern cultural traits, on the other hand, trust is less sensitive to macroeconomic conditions.

Policy implications

These results do not suggest that there is a real and present danger of the EU disintegrating. The UK, they suggest, is an outlier. The crisis has left a toll, but the effects of negative macroeconomic shocks on attitudes towards the EU are not very large. And with economic conditions now improving, attitudes and electoral outcomes ought to turn more favourable to the EU, assuming that history is a guide. We have already seen suggestive evidence of this in recent elections in France and the Netherlands.

Nevertheless, there are grounds for caution. Many of the socioeconomic factors associated with the outcome of the Brexit referendum are also present in other EU countries. In particular, citizens in other EU member states are also divided between those who are optimistic about their future versus those who are pessimistic, and between those who embrace change and globalisation versus those who fear them.

If support for European integration is to be maintained, the EU and national political systems must deliver effective responses to the malaise facing their societies, and the grievances felt, in particular, by older individuals who do not feel that they have shared fully in the fruits of economic growth and have been left behind by technical change and globalisation. Promoting growth and employment, and better protecting those who are hurt by globalisation and technology, should be the priorities. More transparency and accountability at the level of the European institutions are clearly needed. National and EU officials have given lip service to these ideas but taken little concrete action. They should not take improving economic conditions and the receding populist tide for granted.

References

Colantone, I and P Stanig (2016), “Global Competition and Brexit”, BAFFI CAREFIN Centre Research Paper No. 2016-44, Bocconi University.

Dippel, C, R Gold and S Heblich (2015), “Globalization and its (dis-) content: Trade shocks and voting behaviour”, NBER Working Paper No. 21812.

Dustmann, C, B Eichengreen, S Otten, A Sapir, G Tabellini and G Zoega (2017), Europe’s Trust Deficit: Causes and Remedies, Monitoring International Integration 1, CEPR Press.

Dustmann, C, F Fabbri and I Preston (2005), “The Impact of Immigration on the British Labour Market”, The Economic Journal 115(507): F324-F341.

M, M Schularick and C Trebesch (2016), “Going to the extremes: Politics after financial crises, 1870-2014”, European Economic Review 88: 227-260.

Inglehart, R and P Norris (2016), “Trump, Brexit, and the Rise of Populism: Economic Have-Nots and Cultural Backlash”, HKS Working Paper No. RWP16-026.

Endnotes

[1] For a detailed description of the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES), see http://chesdata.eu.