Since the onset of the Great Recession, much of the world has been in a state of economic winter: nearly 50 countries were in recession in 2009 and 15 countries slipped into recession in 2012. After weak global growth in 2013, economic forecasters are predicting a rosier outlook this year and next. Can these forecasts be trusted? Or are forecasters simply intoning – like Chauncey Gardner, the character played by Peter Sellers in the movie Being There – that “there will be growth in the spring”?

The 2008–2012 record

In a classic 1987 paper, William Nordhaus documented that, as forecasters, we tend to break the “bad news to ourselves slowly, taking too long to allow surprises to be incorporated into our forecasts.” Papers by Herman Stekler (1972) and Victor Zarnowitz (1986) found that forecasters had missed every turning point in the US economy.

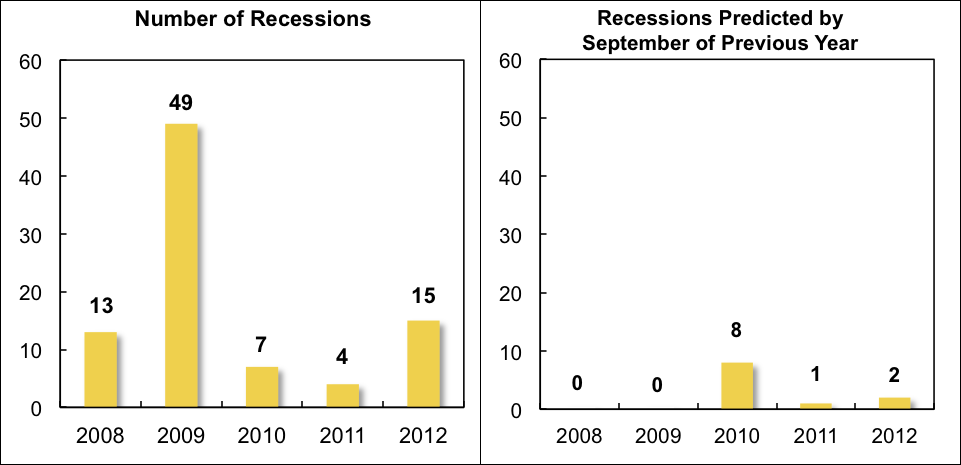

These traits appear to have persisted to this day. In our recent work we look at the record of professional forecasters in predicting recessions over the period 2008-2012 (Ahir and Loungani 2014). There were a total of 88 recessions over this period, where a recession is defined as a year in which real GDP fell on a year-over-year basis in a given country. The distribution of recessions over the different years is shown in the left-hand panel of Figure 1.

Figure 1. Number of recessions predicted by September of the previous year

The panel on the right shows the number of cases in which forecasters predicted a fall in real GDP by September of the preceding year. These predictions come from Consensus Forecasts, which provides for each country the real GDP forecasts of a number of prominent economic analysts and reports the individual forecasts as well as simple statistics such as the mean (the consensus).

As shown above, none of the 62 recessions in 2008–09 was predicted as the previous year was drawing to a close. However, once the full realisation of the magnitude and breadth of the Great Recession became known, forecasters did predict by September 2009 that eight countries would be in recession in 2010, which turned out to be the right call in three of these cases. But the recessions in 2011–12 again came largely as a surprise to forecasters.

A robust finding

In short, the ability of forecasters to predict turning points appears limited. This finding holds up to a number of robustness checks (Loungani, Stekler, and Tamirisa 2013).

- First, lowering the bar on how far in advance the recession is predicted does not appreciably improve the ability to forecast turning points.

- Second, using a more precise definition of recessions based on quarterly data does not change the results.

- Third, the failure to predict turning points is not particular to the Great Recession but holds for earlier periods as well.

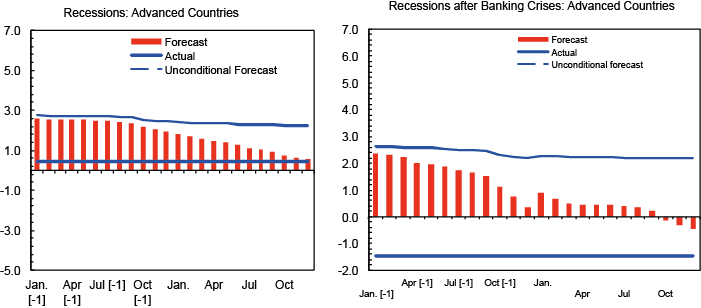

Figure 2. Predicting recessions in advanced economies, 1989–2008

These points are illustrated in Figure 2 above, which presents evidence on how well recessions were predicted in advanced economies over the period 1989 to 2008. Consider the panel on the left. The line labelled ‘unconditional forecast’ shows the normal evolution of forecasts of real GDP growth. On average across countries, forecasters start out by predicting – in January of the preceding year – that annual growth in the following year will be about 3%. This forecast is then lowered slightly over the coming 24 months.

The evolution of forecasts in years that will turn out to be recessions is shown by the red bars. While forecasts in recession years start out very close to the unconditional average, they start to depart from it slightly around the middle of the previous year, suggesting that forecasters are already starting to be aware that the year to come is likely to be a departure from the norm. Major departures of the forecasts from the unconditional average, however, only start to occur over the course of the current year and occur in a very smooth fashion. By the end of the forecasting horizon in December, forecasts are only slightly above the average outcome in recession years, which is shown by the solid blue line. (Note that, on average, growth is not negative during recessions in advanced economies because the dating of recession episodes is based on the quarterly data and annual growth tends to remains positive during many recessions.)

The evidence for recessions associated with banking crises is shown in the right panel of Figure 2. Here, the departure from the unconditional forecast starts earlier than it does for other recessions. This is followed by a smooth pattern of downward revisions to the forecast. In this case, even the terminal forecast greatly underestimates the actual decline, which on average is about 1.5%. To summarise, the evidence over the past two decades supports the view that “the record of failure to predict recessions is virtually unblemished,” as Loungani (2001) concluded based on the evidence of the 1990s.

Are official forecasts any better?

Forecasts from the official sector, either from national sources or international agencies, are no better at predicting turning points. In the case of the US, the March 2007 statement by then-Fed Chairman Bernanke that “the impact on the broader economy and financial markets of the problems in the subprime market seems likely to be contained” has received a lot of attention. Another Fed Chair, Alan Greenspan, told his colleagues in late-August 1990 – a month into a recession – that “those who argue that we are already in a recession are reasonably certain to be wrong.” Forecasts by Fed staff have also missed turning points, as discussed in Sinclair, Joutz and Stekler (2010).

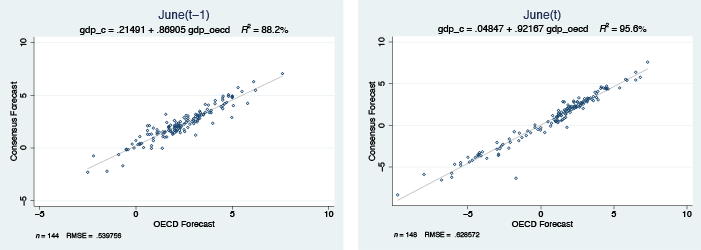

During the Great Recession, Consensus forecasts and official sector forecasts were so similar that statistical horse races to assess which one did better end up in a photo-finish. As an example, Figure 3 compares Consensus forecasts with those made by the OECD. For both the year-ahead forecasts (those made in June of the previous year) and the current year forecasts, the correlation between the two sources of forecasts is extremely high. Hence, an analysis of the OECD’s ability to forecast recessions gives results very similar to those shown earlier for Consensus forecasts.

Figure 3. Correlation between Consensus forecasts and OECD forecasts

For the case of the IMF too, a recent independent evaluation concluded “that the accuracy of IMF short-term forecasts is comparable to that of private forecasts. Both tend to overpredict GDP growth significantly during regional or global recessions, as well as during crises in individual countries” (IMF 2014).

Searching for an explanation

To paraphrase Oscar Wilde, to fail to forecast a few recessions may be misfortune, to fail to forecast nearly all of them seems like carelessness. Do forecasters simply not update their forecasts often enough to be alert to the onset of recessions? That simple possible explanation turns out not to be true. As shown in Figure 2 earlier, the consensus forecasts in recession years are revised every month; they just are not revised down enough to capture the onset of recessions. Related work by one of us – which looks at the behaviour of individual forecasters rather than just the consensus – also finds that forecasts are updated quite often (Dovern, Fritsche, Loungani, Tamirisa, 2014).

So the explanation for why recessions are not forecasted ahead of time lies in three other classes of theories, which are not mutually exclusive.

- One class says that forecasters do not have enough information to reliably call a recession. Economic models are not reliable enough to predict recessions, or recessions occur because of shocks (e.g. political crises) that are difficult to anticipate.

- A second class of theories says that forecasters do not have the incentive to predict a recession, which – though not a tail – event are still relatively rare. Included in this class are explanations that rely on asymmetric loss functions: there may be greater loss – reputational and other kinds – for incorrectly calling a recession than benefits from correctly calling one.

- The third class stresses behavioural reasons for why forecasters hold on to their priors and only revise them slowly and insufficiently in response to incoming information (Nordhaus 1987).

Regardless of the explanation for why recessions fail to be forecasted, the evidence suggests that users of these forecasts need to be cognizant of this feature. Forecasters may be predicting that “there will be growth in the spring” but their ability to predict a sudden snowstorm is rather limited.

References

Ahir, Hites and Prakash Loungani (2014), “Fail Again? Fail Better? Forecasts by Economists During the Great Recession”, George Washington University Research Program in Forecasting Seminar.

Dovern, Jonas, Ulrich Fritsche, Prakash Loungani, and Natalia Tamirisa (2014), “Information Rigidities: Comparing Average and Individual Forecasts for a Large International Panel”, IMF Working Paper 14/31.

IMF, Independent Evaluation Office (2014), “IMF Forecasts: Process, Quality and Country Perspectives”.

Loungani, Prakash (2001), “How accurate are private sector forecasts? Cross-country evidence from consensus forecasts of output growth”, International Journal of Forecasting, 17(3).

Loungani, Prakash, Herman Stekler, and Natalia Tamirisa (2013), “Information rigidity in growth forecasts: Some cross-country evidence”, International Journal of Forecasting, 29(4).

Nordhaus, William (1987), “Forecasting Efficiency: Concepts and Applications”, Review of Economics and Statistics, 69(4).

Sinclair, Tara M, Fred Joutz, and Herman Stekler (2010), “Can the Fed predict the state of the economy?”, Economics Letters, 108(1).

Stekler, Herman (1972), “An analysis of turning point forecast errors”, American Economic Review, 62.

Zarnowitz, Victor (1986), “The Record and Improvability of Economic Forecasting,” NBER Working Paper 2099.