In the past twenty years, the share of developing and transition countries in the global foreign direct investment (FDI) outflows has doubled, reaching 16% of the total FDI outflow stock. Most of this increase has happened since 2004 (UNCTAD 2010). This process has not only been driven by an active role of China, whose share amounts to 8.5% of the total FDI stemming from the South. Other important investors are Brazil, Hong Kong, India, Malaysia, Mexico, Russia, South Africa, South Korea, Singapore, and the UAE, who together account for almost 80% of the total FDI outflows from the South in 2010. Since most of the investment flows from developing countries go to other developing and transition economies, this gives rise to the term “South-South FDI”. Such flows amount to one-third of the total FDI inflows in emerging economies (Aykut and Ratha 2004).

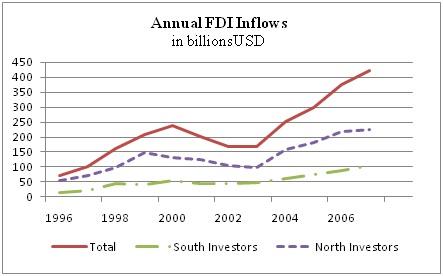

Figure 1. The dynamics of FDI inflows

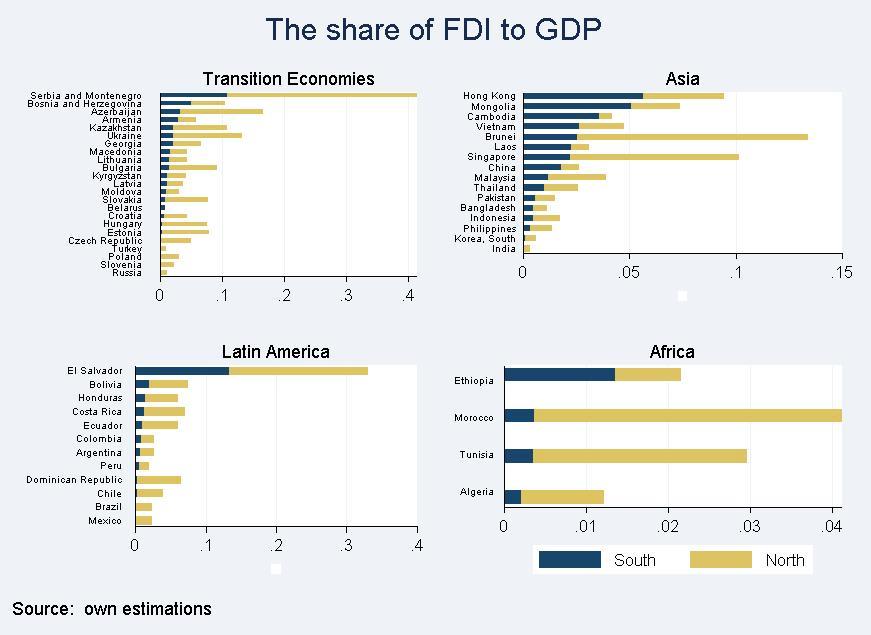

Figure 2. The share of FDI inflows to GDP in selected developing and transition economies, 1996-2007

The appearance of these new global investors has been described as a “huge infusion” or a “bonanza” in the popular media, reflecting large amounts that are being invested. A considerable amount of this investment has been driven by investment in natural resources, and in particular, oil and mining sectors, reflecting their growing strategic importance, which is also due to increased demand and soaring prices. For example, to mitigate the domestic shortage of natural resources, the Chinese government has promoted outward FDI for resource exploration projects via preferential bank loans of the Export-Import Bank of China. As a result, between 2003 and 2005, the mining industry has accounted for 32% of the total outward Chinese FDI, albeit its share has decreased afterwards. The government of India has also mandated its state-owned oil companies to secure stakes in oversea oil deposits. Although Russia does not need to secure resources for its own demand, it has still engaged in the competition for resources in the post-Soviet republics with the aim of selling them in international markets. Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, for instance, are large producers and exporters of natural gas, but they find it difficult to export due to restrictions on their access to the Russian Federation transit pipelines.

In the global quest for resources, new emerging investors from the South often make investment choices that seem to ignore the overall investment climate and political institutions of receiving countries. Yet, in the traditional literature on FDI, bad institutions are usually considered an additional entry barrier that deters FDI. Poor institutional quality of potential host countries is often cited as the leading explanation for the scarcity of capital flows to poor countries predicted by the standard neoclassical theory – the ‘Lucas Paradox’ (Lucas 1990). More recently, studies have shown that investors from the North are repelled not just by bad institutions, but by institutional differences between source and destination countries. Northern investors prefer investing into countries with institutionally similar environments and avoid countries with much worse or much better institutions (Bénassy-Quéré et al 2007). The lack of data on investors from the South has prevented an empirical testing of the relevance of this hypothesis for South-South FDI.

In a recent research paper (Aleksynska and Havrylchyk 2011), we are able to test the above hypothesis for a sample of countries in the South and demonstrate that FDI from the South has a systematically different pattern than FDI from the North. First, it has a more regional character than FDI stemming from the North. Second, our findings on institutional differences and natural resources as determinants of these FDI allow us to group South investors into three categories.

- Investing in better institutions These are the investors from the South that choose countries with the best possible institutional environment and, in this case, appear not to be deterred by an “institutional distance”. Such large institutional difference is a driving force for the “asset-seeking” nature of FDI, as emerging investors acquire new technologies, brands, and intellectual property. Despite unfamiliarity, such an institutional environment is the most transparent for potential entrants due to the low corruption, sound property rights, and political stability.

- Investing in similar institutions.These are the investors from the South that choose countries with a similar institutional environment, which helps explain the phenomenon of South-South FDI. When investing in the South, these investors have a comparative advantage due to their experience of working with poor institutions at home.

- Investing in worse institutions. Although investors from developing countries often invest in countries with similarly poor institutions, they are usually deterred by institutions that are much worse than at home. Yet there is an important exception to this rule. The negative effect of very poor institutions is systematically outweighed by the appeal of natural resources, which appears to be a very important force behind FDI from the emerging economies. Specifically, we find that countries possessing natural resources that are worth more than $4,675 per capita (in the top 10% of our sample) will attract FDI from investors from the South despite a large institutional distance and having worse institutions. To name a few, this concerns countries such countries as Algeria, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Russia, and Venezuela.

One of the reasons why the South’s countries close their eyes to poor institutions in host countries is related to the investors’ ownership form. In fact, companies from the South that invest in the primary sector are almost always state-owned and, hence, they could be influenced by considerations other than economic. In a study of Chinese outward direct investment, Buckley et al (2007) show that when choosing an investment location Chinese firms prefer countries with higher political risk, even after controlling for the rate of return. They suggest that such behaviour could be led by state-owned firms that do not maximise profits or could be due to close political ties between China and other developing host countries, where the bargaining position of Chinese firms may have been strengthened, because these host countries receive only a modest amount of FDI from developed economies.

Another reason for investing into worse institutional environments by South companies is related to the FDI-receiving countries’ responsiveness to strategically important acquisitions. Well-functioning institutions in the North can efficiently react to and block investments from the South if they are strategically undesirable. For example, in 2004, China Minmetals was ready to invest $6.7 billion into the acquisition of Canada's largest mining company Noranda. Canadian public opinion virtually exploded and pressed the Canadian federal government to intervene. The investment efforts of the Chinese state-owned corporation were aborted. As a result of these and similar actions, the South’s investors may simply be left with investment opportunities in only those countries where such opportunities are institutionally easier to seize. Moreover, they may also intentionally direct their effort into the environments suffering from the ’resource curse’, that is, possessing natural resources but suffering from poor institutions.

Our analysis implies that countries with bad institutions do not necessarily have to improve their quality in order to attract investors. They may still see considerable investment inflows, albeit from a different type of investors and into different sectors, such as the primary sector. This, however, can present problems for receivers of such investments, if their resources are disproportionally drawn out, and if the benefits of such investments are not properly shared. In addition, ignoring bad institutions in a search of natural resources could also pose serious problems in the future for the investors themselves.

References

Aleksynska, M and O Havrylchyk (2011), “FDI from the South: the Role of Institutional Distance and Natural Resources”, CEPII Working Paper 2011-05.

Aykut, AD and D Ratha (2004), “South-South FDI Flows: How Big Are They?”, Transnational Corporations, 13(1):149-176.

Bénassy-Quéré, A, M Coupet and T Mayer (2007). “Institutional determinants of foreign direct investment”, the World Economy,30(5):764-782.

Boston Consulting Group (2006), “The New Global Challengers. How 100 Top Companies from Rapidly Developing Economies are Changing the World. A Report”, Boston.

Buckley, PJ, J Clegg, AR Cross, X Liu, H Voss, and P Zheng (2007), “The determinants of Chinese outward foreign direct investment”, Journal of International Business Studies, 38(4):499-518.

Lucas, Robert E (1990), “Why Doesn’t Capital Flow from Rich to Poor Countries?”, American Economic Review, 80:92-96.

UNCTAD (2007), “Transnational Corporations, Extractive Industries and Development”, World Investment Report

UNCTAD (2010), “Investing in a Low-Carbon Economy”, World Investment Report.