Like other communication networks, broadband is seen as a main driver of economic activity and growth (Czernich et al. 2011). The potential benefits of broadband are considerable, but so are its rollout costs. Large, sunk infrastructure investments also create market power. Thus the telecom industry has traditionally been subject to some form of regulation. European countries oblige the incumbents to open their networks to entrants; the European Commission has required the implementation of so-called ‘local loop unbundling’ (LLU) to promote competition in the telecom sector1. In stark contrast with the EU approach, the Federal Communications Commission has eliminated all open access requirements in 2003 and 2004.

Incumbents have generally opposed the view of open access to their networks, arguing that open access amounts to a regulatory taking and will reduce the incentives of entrants to build their own infrastructure. In contrast, new entrants argue that they cannot afford to duplicate the incumbent's infrastructure, so that they can only compete if they have access to the incumbent’s network.

Is local loop unbundling desirable?

Although the question on the desirability of local loop unbundling entry is of key importance to policymakers and market regulators, there has not been much sound empirical analysis by the academic world. Because of data limitations, most studies have had to rely on aggregate cross-country comparisons with limited information on broadband performance indicators and difficulties in identifying the causal effects of open access on performance (e.g. Wallsten and Hausladen 2009; Bouckaert, Van Dijk and Verboven 2010; Gruber and Koutroumpis 2012).

In our recent research (Nardotto, Valletti and Verboven 2012), we analyse the unbundling experience in the UK, based on two unique new datasets: one on broadband penetration, collected by Ofcom (the UK's communication regulator); and one on broadband speeds, obtained from a private company. The unit of observation of both datasets is the ‘local exchange’ (LE), which corresponds to more than 5,000 highly disaggregate geographical areas. This makes it possible to obtain a substantial understanding of the unbundling process in the period between December 2005 and December 2009, in particular how entry has affected broadband penetration and quality (as measured by speed) throughout the country.

An analysis of the UK experience is particularly interesting in that it has both a large traditional telephone network (owned by the BT group), which is subject to access regulation, and a well-established cable network that has never been required to offer its facilities to competitors. We can thus analyse both the impact of inter-platform competition – cable vs traditional telcos – and intra-platform competition (whereby entrants access BT's network).

Local loop unbundling entry

In a first step we describe the process of local loop unbundling entry. Our analysis reveals an interesting, complex picture. Figure 1 documents a strong increase in local loop unbundling entry in the UK over the period 2005-2009, albeit characterised by considerable heterogeneity across local markets. Over the period, the areas with local loop unbundling entry trebled, going from 695 LEs at the end of 2005 to 2,011 at the end of 2009. Moreover, at this date, local loop unbundling was potentially available to 85% of the UK population.

Figure 1. Diffusion of local loop unbundling investments over time. Local exchanges without local loop unbundling (white) and with at least one local loop unbundling operator (red)

A more detailed analysis shows that larger markets support a greater number of entrants, thus confirming the importance of high fixed investment costs. Entry is highly persistent over time, implying that technology exhibits substantial sunk costs. Finally, entry is more likely in adjacent areas where there is already local loop unbundling coverage, which shows there are agglomeration advantages or ‘economies of density’ at play here.

Broadband penetration

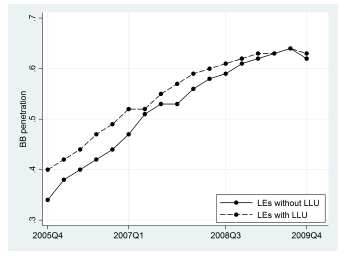

In the second step, we study broadband penetration and its determinants, and in particular the role of local loop unbundling entry. Broadband penetration is calculated as the fraction of households in a given area with a broadband subscription. Figure 2 shows that, during the period in which entrants progressively unbundled local loops, penetration more than doubled in the UK. However, apart from this upward trend, those areas with local loop unbundling do not seem to obtain higher penetration levels than those without. In fact, areas where there was no local loop unbundling entry even grew faster. Indeed, they appear to have caught up with the areas where there was local loop unbundling entry.

Figure 2. Broadband penetration in local exchanges with and without local loop unbundling.

Intra- and inter-platform competition and broadband penetration

The suggestive evidence from Figure 2 is confirmed by an econometric analysis using various different identification strategies. Our main finding is that intra-platform competition (through local loop unbundling entry) either had no effect or raised local broadband penetration by, at most, 1.4% in the long run. In contrast, inter-platform competition (from cable) has increased local broadband penetration by 3.4%.

The absence of any strong positive effects of local loop unbundling entry on broadband penetration levels would seem to suggest that the positive competitive effects are outweighed by the adverse effects of reduced investment incentives. Before drawing such a conclusion, however, we need to consider how local loop unbundling entry has affected the quality of the service offered, through our measure of broadband speed.

Has local loop unbundling affected broadband speed?

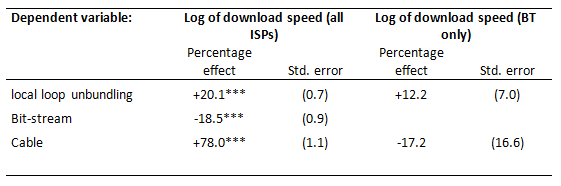

This brings us to the third stage of our analysis, as summarised in Table 1. As expected, the speed test data show that local exchanges characterised by inter-platform competition are the ones boasting the highest average speed; users of cable have 78% faster broadband than users of BT. More interestingly, the local exchanges that have experienced local loop unbundling entry display a higher average broadband speed than those that have not experienced local loop unbundling entry. Users who subscribed to an local loop unbundling operator have 20.1% higher speed than users of BT. Remarkably, this higher speed is entirely due to the local loop unbundling entrants: as shown in the right column, BT does not significantly react to local loop unbundling entry by raising its speed selectively in those areas with local loop unbundling. Instead, the incumbent provides quality uniformly across the country.

Table 1. Impact of local loop unbundling on broadband speed

Notes: Based on regression of log of download speed on dummy variables for local loop unbundling, Bit-stream and Cable. The regression also includes a constant and the following control variables: urban status of LE, distance between the location of a user and the LE (significant negative effect on speed) and dummy variables for hour and day (much stronger effects during peak hours and days). “***” indicates statistically significant at the 1% level or higher.

We also offer evidence that local loop unbundling entrants compete by differentiating their offers ‘upwards’ compared with BT. They have focused on the high end of the market, drawing high-speed users away from the incumbent by offering them a better quality service. On the other hand, in those areas where entry via local loop unbundling has not occurred, entrants were nonetheless able to use the incumbent's network (via bitstream), although they could not differentiate themselves in terms of the service provided, and thus could compete only along the price dimension. The combination of regulated bitstream access prices with a relatively homogeneous product, explains why penetration in non-local loop unbundling areas has not suffered compared to those areas with local loop unbundling entry, despite the former being typically rural and scarcely inhabited.

Conclusions

While local loop unbundling entry has not raised total broadband penetration across different local markets, it has substantially increased the quality of the service as measured by average broadband speed.

References

Czernich N, O Falck, T Kretschmer and L Woessmann (2011), „Broadband Infrastructure and Economic Growth”, Economic Journal, 121(552), 505-532.

Wallsten, S and S Hausladen (2009), “Net Neutrality, Unbundling, and their Effects on International Investment in Next-Generation Networks”, Review of Network Economics, 8(1).

Bouckaert, J, T van Dijk and F Verboven (2010), “Access regulation, competition, and broadband penetration: An international study”, Telecommunications Policy, 34, 661-671.

Gruber, H and P Koutroumpis (2012), “Competition enhancing regulation and diffusion of innovation: The case of broadband networks”, mimeo.

1 Regulation (EC) No 2887/2000 of the European Parliament on unbundled access to the local loop.